Jul / Aug 2020

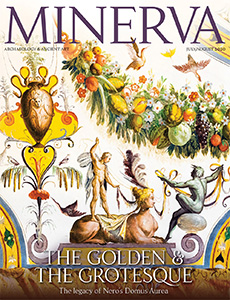

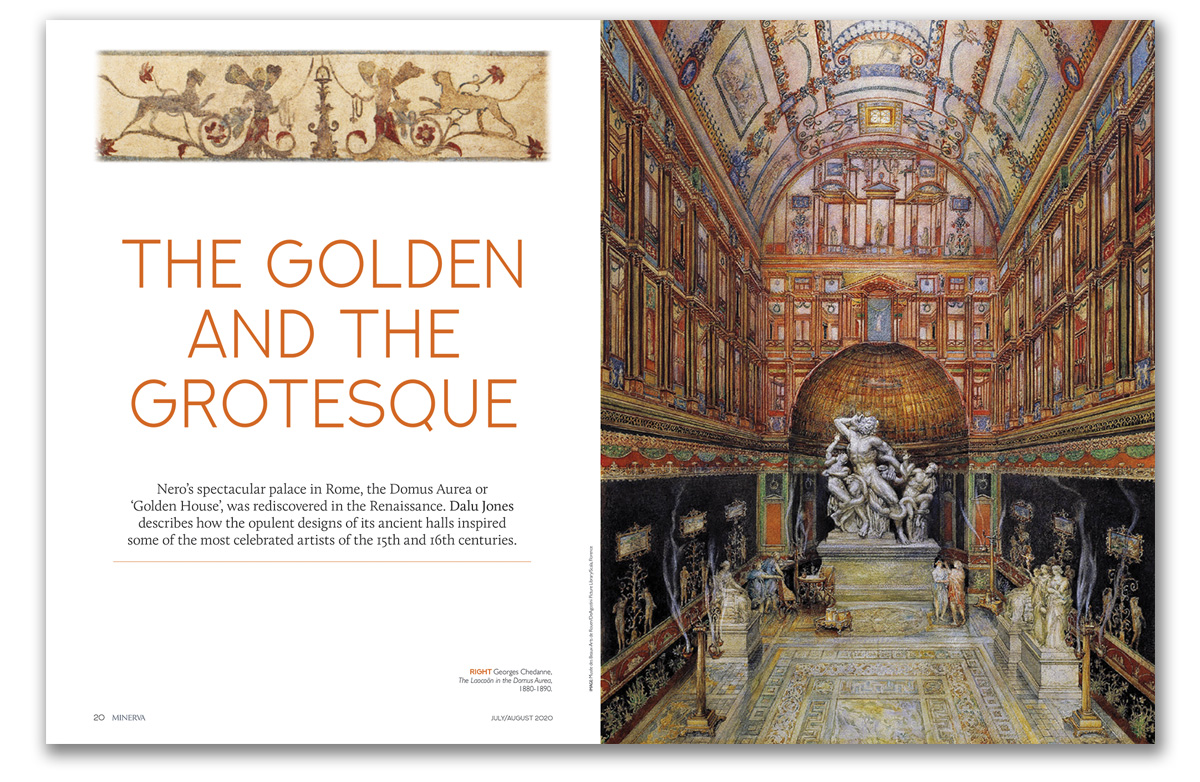

In around 1480, a young Roman tumbled through an opening in the side of the city’s Oppian Hill, and emerged, wide-eyed, amid the remains of Nero’s 1st-century AD Domus Aurea.

In 17th century England, another form of fanciful depiction arrived with the restoration of the monarchy. Charles II is portrayed in 1674 in the guise of a Roman emperor, conqueror of sea and land – with all the attributes and symbols associated with supreme power. There was no doubt here about who was back in charge. In such ways, the Baroque style in Britain came to be used as a visual language – one that redefined order and authority declaiming that the new world order was here to stay.

The ancient cities of that mysterious land Illyria – mythical setting for Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night – are mostly to be found in modern-day Albania. But despite a fascinating history that stretches back through prehistory, classical Greek and Roman times, they still remain littleknown. Oliver Gilkes guides us through the ancient treasures of one of Europe’s smallest and least-understood countries.

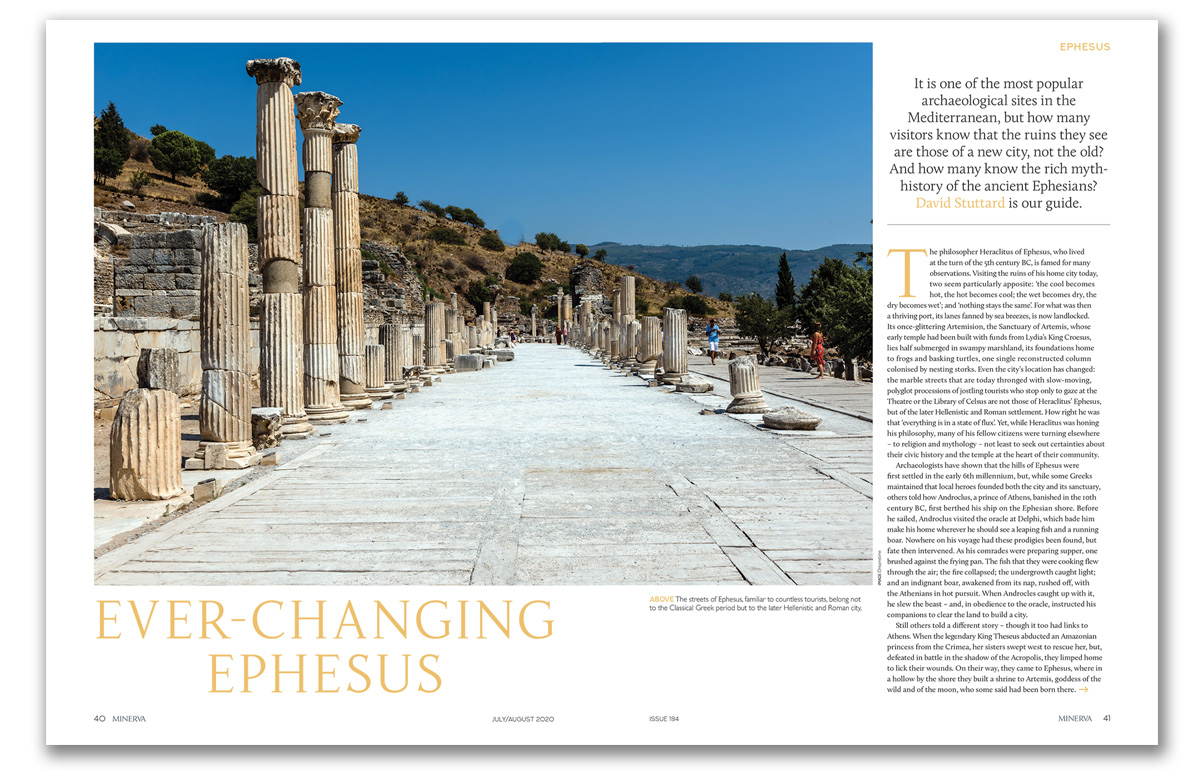

The mythical origins of another spectacular ancient city are explored in our feature on page 40. Was the city really founded there because the Oracle of Delphi told a prince of Athens that he should settle where he found a leaping fish and a running boar? Or because fleeing Amazons built a shrine to Artemis in the place believed to be her birthplace? David Stuttard narrates the rich myth-history of Ephesus.

Finally, no such conjecture is needed about life in Mesopotamia 4,000 years ago. The first major cities were born there, and with those structures came bureaucracy - a necessity for ordering what became complex city-states – and, of course, writing, for recording that bureaucracy. Neil Faulkner surveys an exhibition that displays the extraordinary cultural and scientific achievements of the region. You can read an extract of this article here.