Mesopotamia: Civilisation Begins

Neil Faulkner reports on a new Getty Villa Museum exhibition focused on the huge cultural contribution of the world’s oldest civilisation.

Musée du Louvre. Copyright: RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY. Photo: Mathieu Rabeau.

He lived more than 4,000 years ago, at the dawn of civilisation. He was war leader, high priest, hydraulic engineer, and first minister – all rolled into one – of the Sumerian city-state of Lagash from 2144 to 2124 BC. His name was Gudea, and because we know a surprising amount about him, he looms large in the new Getty Villa Museum exhibition Mesopotamia: civilisation begins.

Gudea adopted the title ensi, which might be translated ‘city-king’ or ‘city-governor’. He had married into the royal house of Lagash, and in due course succeeded to the supreme position. But Sumerian city-state rulers cannot be equated with the kings and princes of later ages. What chiefly characterised a man like Gudea was the extraordinary combination of roles combined in one person.

Statue of Prince Gudea, City-Governor of Lagash, wearing the flat hat of a priest, and holding as vase of flowing water, associating him with irrigation works and the Sumerian water god Enki. Neo-Sumerian period, about 2120 BC. Dolerite.

© Musée du Louvre.

The Land of Shinar

Let us set him in context. Ancient Sumer – the Biblical land of Shinar – lay astride the Tigris and Euphrates river system of Lower Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq). In the Early Copper Age (or Chalcolithic), the mid fourth millennium BC, it was a region of vast swamps, of slow, sluggish, muddy rivers and streams, of towering reeds and date palms; it teemed with fish, foul, and other wild game.

Compared with the desert wastes on either side, this watery jungle was a paradise for hunters. But let it once be tamed, let the waters be canalised and the swamps drained, and the result would be fields of alluvial soil of such exceptional richness that Sumer might become a veritable Garden of Eden.

This was the transition carried out in the final centuries of the fourth millennium. It required massed labour to achieve – to straighten and deepen channels, to build protective banks, to divert and manage the waters. It required continuing massed labour to maintain – to dredge channels, restore banks, repair flood damage.

But the result was unprecedented agricultural wealth. Documents from 2500 BC record that the average yield on a field of barley was 86 times the sowing.

Such bounty – such great surpluses of produce – allowed a further transition to be made: from the Copper Age villages of the fourth millennium BC to the Bronze Age cities of the third.

By later standards, Sumerian civilisation was small in scale. Sumer as a whole was about the size of modern Denmark, and even the larger cities might extend across only one or two square miles. Records for Lagash – city and countryside – imply a population of about 36,000 adult males, so perhaps 100,000 people in total.

But by comparison with everything that had gone before, this was a veritable ‘urban revolution’, a massive qualitative leap in the scale and complexity of human social organisation. And it created the basis for a cultural explosion.

‘The achievements of this culture,’ explains Getty curator Tim Potts, ‘influenced not just life in Mesopotamia, but are with us still today.’ These include writing, measurement, arithmetic, geometry, time-keeping, and money.

Much of what we know about this civilisation is down to the invention of writing and the keeping of records – that is, to the existence of bureaucracy – for the Sumerians not only created official documents, but also filed them in the form of baked clay tablets.

Musée du Louvre. © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY. Photo: Franck Raux.

A cult of the personality

But this, of course, came long after the original schemes of drainage and reclamation. The Sumerians had no records of their own origins. Indeed, Gudea of Lagash ruled more than a thousand years after the earliest efforts at large-scale hydraulic engineering. The yawning gaps in historical knowledge were filled by the myths of Mesopotamian religion.

Some two dozen statues of Gudea are known. Several are featured in the Getty exhibition. One shows the city-governor holding a vase from which water flows down either side of his gown into two vessels at his feet. Fish can be seen swimming upstream towards the vase in his hands. What does this mean?

This and other images of Gudea show him wearing the flat hat of a priest. The Sumerians imagined the life-giving waters of their rivers and the fertility of their fields to be gifts of the gods. Their greatest urban monuments were large temples and artificial mounds known as ziggurats. An early ziggurat at Erech, for example, was ten metres high, built of sun-dried bricks, faced with thousands of pottery goblets, and topped by an asphalt platform.

The temples, and estates in the surrounding countryside that supported them, belonged to the gods. The territory of Lagash was divided among some 20 deities. The goddess Baü owned 44 square kilometres.

In the absence of Baü herself, this property was managed on her behalf by temple priests. They were well rewarded for their efforts. While many of Baü’s people – tenant farmers on her estate – held only one hectare, sometimes only a third of a hectare, one senior-ranking temple official is known to have held more than 14 hectares. As for the city-governor – who was also the high priest – he held no less than 246 hectares.

Thanks to the meticulous record-keeping of the Sumerian bureaucracy, we can say more. The tenant-farmers on Baü’s estate paid a seventh or an eighth of their produce to the temple in rent. These rents enabled the priests to employ 21 bakers, assisted by 27 female slaves, 25 brewers, with six slaves, and 40 women textile workers.

We even learn something of the social tensions in this obviously class-based society. An official decree setting out to restore the old order of Lagash ‘as it had existed from the beginning’ lists various abuses of power: priests who were stealing from the poor, practising sundry kinds of extortion, and treating temple land, cattle, equipment, and servants as their private property.

Divine right

The priests derived their legitimacy from the belief that the fertility and prosperity of the land were in the gift of the gods, and that they were chosen by the gods to represent them.

A cylinder seal in the exhibition – that of the royal scribe Ibni-Sharrum – is one object among many that shows this relationship. As well as having a very practical use – ‘like a modern signature’ – these ubiquitous objects were ‘miniature canvases’, their finely worked depictions rich in symbolic meaning. That of Ibni-Sharrum shows two water buffaloes and two figures with vases, from which water flows into a channel running beneath.

In this scene, surely, we bear witness to Enki, the Sumerian god of water. For Tim Potts this image is ‘a representation of the relationship between man, nature, and the gods’.

Sumerian rulers saw themselves as primary agents in the articulation of this relationship. ‘The fact that Gudea is in the role of holding this vase,’ says Potts of the statue in question, ‘is associating him with that underworld, reinforcing his role in the fertility and renewal of life in Mesopotamia.’

Gudea rules by divine right. ‘The Mesopotamians did think about kingship as something that was in the gift of the gods. The gods are the ones who select the worthy person who can become king.’

A central obligation on the ruler, therefore, was the building and maintenance of temples and ziggurats, and the regular performance of appropriate holy rites. Unsurprisingly, then, another of the many statues of Gudea shows him in the guise of architect, seated with a tablet on his lap, presumably giving design specifications.

This involved further duties: accessing the many raw materials necessary to temple construction and ritual that Mesopotamia, for all its agricultural fertility, could not supply – timber, metals, stone for tools, precious stones for decoration, and also gold and silver.

The wood may have come from Iran or Syria, copper from Oman, tin from Iran, Syria, Asia Minor, even Europe, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, and mother-of-pearl from the Persian Gulf. These are long-distance connections, and we must imagine the implications – the caravans and desert trading posts, the merchant ships and ports, the diplomatic arrangements and payments of protection money to local tribal leaders.

So Sumer’s vast surpluses not only sustained an urban civilisation and a ruling elite; they gave rise to a merchant class and a web of trade lines extending for thousands of miles. As well as giant grain-stores, there must have been warehouses full of precious commodities.

Musée du Louvre. Copyright: Musée du Louvre/RMN-Grand Palais/Thierry Ollivier/Art Resource, NY.

Great wealth had to be defended – against ‘barbarians’ in the wilderness all around, against rival city-states in a fragmented polity, and, not least perhaps, against the mass of peasants, labourers, and slaves who formed a potential ‘enemy within’.

So Gudea was also a war-leader, the commander of the army of Lagash – which might have comprised four-wheeled chariots pulled by asses and a phalanx of armoured spearmen – if the evidence of the famous ‘Standard of Ur’ (to be seen in the British Museum) is any guide.

It was this extraordinary and unprecedented social complexity that made men like Gudea into the world’s first bureaucrats, standing at the head of cohorts of clerks and accountants working in the offices of the state.

An information revolution

The life of a Copper Age village of a few dozen people required no records; memory and oral communication sufficed for all the requirements of everyday life. But here were city-states of 100,000 people, ranked in a social hierarchy, arranged in a division of labour, each person with obligations, duties, entitlements. Who owed what to whom? How many bushels of barley or pots of honey? How many fleeces or hides? What was held in store, and what disbursements were due?

And what of those great construction projects? How much wood, brick, ceramic, and precious stone to build a temple or a ziggurat?

Then there was the army. The chariots, the horses, the armour, the arms: how many, in what condition, what replenishment was necessary?

So the Mesopotamians not only created bureaucracy, but also invented its essential tools: writing, measurement, arithmetic. They carried out an information revolution as transformative as the later invention of paper, printing, the computer, or the worldwide web.

Musée du Louvre. Copyright: RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY. Photo: Franck Raux.

Writing is an agreed set of representative symbols that allows information to be recorded and transmitted over time, it being fully comprehensible to a wide range of others. Such is the quality of the Mesopotamian archaeological record that we can see the evolution of writing from its most basic form around 3400 BC.

The symbols on the oldest tablets were ‘pictograms’ – simplified but recognisable drawings of an object, concerning which some record was required. Over time, presumably to speed the process of recording, the pictograms became increasingly stylised, sometimes ceasing to be universally recognisable, but of course remaining so to the literate clerks of the state administration.

But not everything lent itself to direct pictographic representation. An concept like tribute or debt, or the name of a particular tributary or a debtor, could not be rendered by a pictogram. To record such things required a further leap, to ‘ideograms’, which were arbitrary but agreed symbols for the expression of a concept or a name in writing.

A further possibility then arose. Many everyday things were known in Ancient Sumerian by single-syllable words. The word for mouth, for example, was ka. This was represented by a human head, but in fact two things were thereby written, not only the object mouth, but also the sound ka. So writing was now capable of becoming ‘phonetic’ – a record of sounds which, in combination, could be made to represent multi-syllable words.

Writing developed rapidly in the first century or two of Sumerian civilisation, and by 2500 BC at the latest the phonetic system was being used to transcribe the names of city-state rulers. Moreover, what had begun as a device for creating state records was being used to transform a tradition of orally transmitted myths into literature.

‘For the Mesopotamians, writing was a key bureaucratic invention, recording transactions, agricultural activity, and so on,’ says Potts, ‘but within a few hundred years it began also to be used for writing literature, myths about the gods and the heroes of earlier times.’

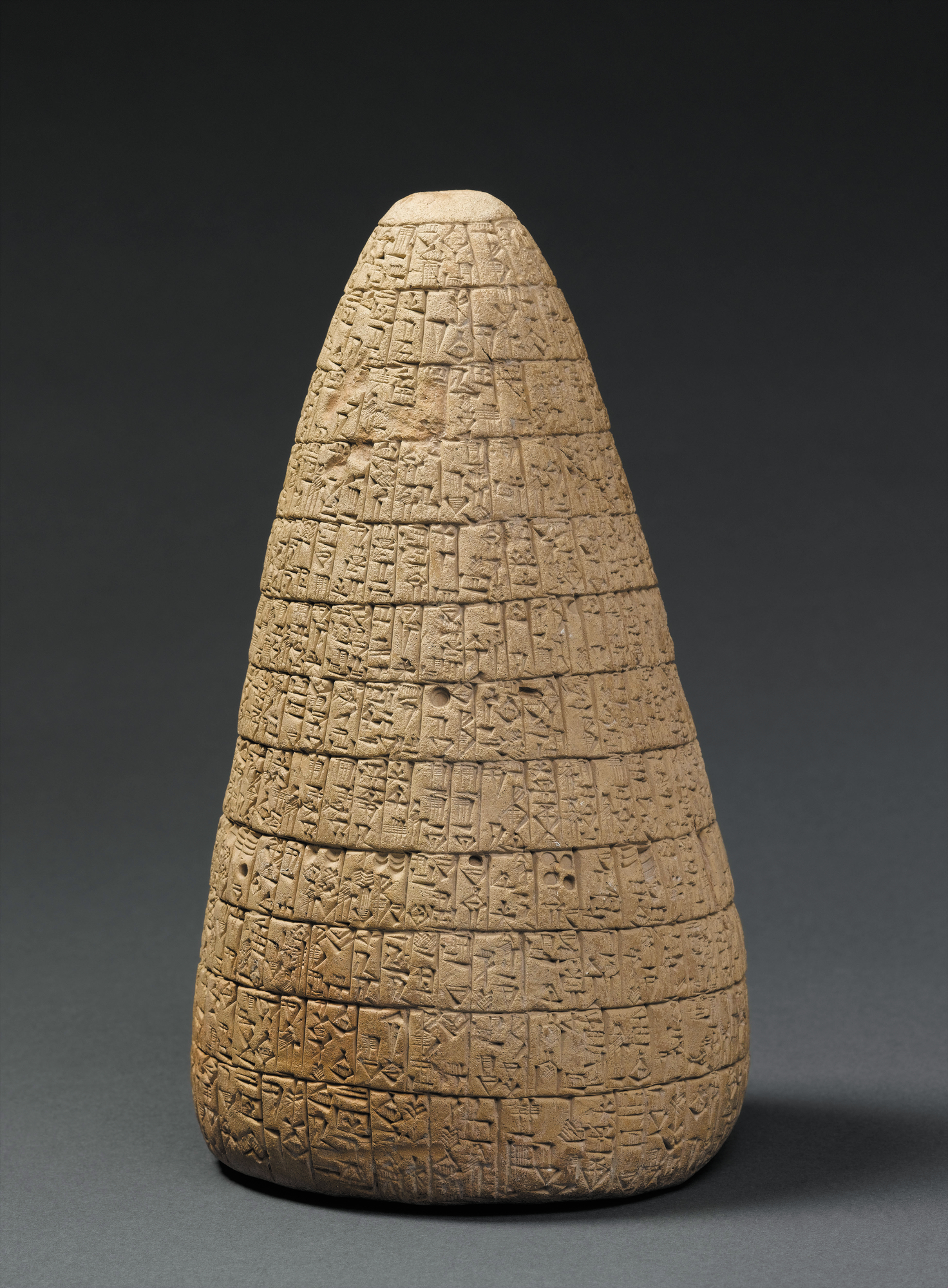

As important as the invention of symbols was the creation of a technique for using them. This was cuneiform (‘wedge-shaped’). By 2600 BC, the Sumerian pictograms and ideograms became highly simplified to the point where they could be rendered in the form of impressions in clay made by a wedge-headed stylus.

Musée du Louvre. Copyright: RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY. Photo: Christian Larrieu.

And of course, official documents must be authenticated, must they not? Included in the Getty exhibition is a collection of cylinder seals, which were functional in that each senior official had his own and would roll his unique mark across the soft clay of a document to validate it, but were also prestige objects, bearing intricate designs, the quality a measure of the standing of the owner, the choice of images a reflection of his role, status, and identity.

The scenes depicted ranged from everyday activities like banqueting, ploughing, and making pottery, to mythology, ritual, and warfare, such that these small but intricately worked objects become the largest and most important surviving body of Mesopotamian iconography and artistry.

In addition to a script, the Sumerians needed a system of notation. Simple societies working with small numbers could manage with notches on a tally-stick, one bushel or sheep or whatever being rendered by one notch. But how were the vast flocks of Baü or the city grain-stores of Lagash to be recorded?

The Sumerians devised two systems of notation, a decimal system used for addition and a sexagesimal one (based on 60) for measuring volume. In the former, for example, numbers from one to nine were rendered by the semi-circular impressions of a reed pen, but ten was rendered by a circle, 20 by two such circles, and so on. Eventually, the decimal system disappeared, and all Mesopotamian numerical notation became sexagesimal – perhaps an early example of bureaucratic rationalisation.

Other innovations included fixed units of measurement (useful in laying out fields and designing temples), standardised weights and measures (essential in levying tribute, making disbursements, and market exchanges), and the invention of the first clocks (sundials and water-clocks operating on the hour-glass principle).

Most of the great advances – setting in place many of the foundation-blocks of human civilisation – took place at the very beginning of Mesopotamian civilisation. The heavily top-down society created – tightly controlled by an elite of governors, priests, and bureaucrats with a vested interest in the status quo – became conservative and resistant to further change. This no doubt included Gudea, the arch Sumerian bureaucratic ruler who looms so large in the surviving record. But the sophistication he and his kind represent is astonishing.

‘The ancient land of Mesopotamia,’ says Tim Potts, ‘occupies a unique place in the history of human culture. It was there, around 3400-3000 BC, that the first major cities arose, boasting massive city walls, temples, and palaces; the first known writing on clay tablets, used by priestly bureaucracies to record agricultural activities; sculptures of gods, worshippers, and rulers; and many other remarkable cultural and scientific achievements.’

The Getty Villa Museum’s exhibition Mesopotamia – Civilisation Begins was scheduled to run from 18 March to 27 July 2020, but is currently closed due to the coronavirus pandemic; a decision is pending on future opening. However, information about the exhibition, including a 45-minute virtual tour in the company of curator Tim Potts, can be found on the Getty Museum website at getty.edu/art/exhibitions/mesopotamia/

The book of the exhibition, Mesopotamia – Civilisation Begins, by Ariane Thomas and Timothy Potts (ISBN 978-81606066492) is available from Getty Publications/Yale University Press, price £50