Art and identity: exploring the ancient Middle East in the age of the Roman and Parthian Empires

Blair Fowlkes-Childs and Michael Seymour, co-curators of a new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that explores the ancient Middle East in the age of the Roman and Parthian Empires, take us on a fascinating journey visiting the cities of Jerusalem, Petra, Sidon, Baalbek, Palmyra, Hatra and Babylon en route

Drawing together some 190 works of art from 20 museums in the Middle East, Europe and the US, as well as objects from the Metropolitan Museum's own collection, a new exhibition entitled The World between Empires: Art and Identity in the Ancient Middle East, covers a period when two great powers, the Roman Empire in the west and the Parthian Empire in the east, competed for control of the Middle East and its lucrative trade routes between circa 100 BC and AD 250. But the empires themselves form only the backdrop to the main story: the exhibition's real subject is the cultural, religious and even personal identities of people and communities in the region that formed the edge of the two empires as expressed through art.

Following ancient trade routes across the Middle East, the journey begins in south-western Arabia tracing caravan routes, famous for spices and incense, heading north through Judaea and the Phoenician cities of the eastern Mediterranean coast, then east, crossing through the Syrian Desert and ending in Mesopotamia. En route it passes through cities such as Petra, Jerusalem, Sidon, Baalbek, Palmyra, Hatra and Babylon. The regions and cities through which the show travels each had distinctive traditions but were also deeply interconnected, and their art often reveals the ways in which they influenced one another.

In recent years, there has been substantial damage to several of the iconic archaeological sites featured in the exhibition – these include Palmyra and Dura-Europos in Syria and Hatra in Iraq, as well as sites in Yemen – and also to some of the region's most important museums through looting, armed conflict and deliberate destruction. These events and responses to them are discussed alongside the ancient material, aiming to provide visitors with a sense of how the Middle East's ancient cultural heritage has been affected, and how these events have played a role in ongoing humanitarian crises.

Filmed interviews with three archaeologists are on view in one of the galleries. Michel Al-Maqdissi, formerly Director of Excavations and Archaeological Studies at the Department of Antiquities of Syria and currently a researcher at the Musée du Louvre in Paris, and Michał Gawlikowski, Professor Emeritus at the University of Warsaw and former director of the Polish Archaeological Mission in Palmyra, focus on sites in Syria, particularly Palmyra, while Zainab Bahrani, Edith Porada Professor of Ancient Near Eastern Art and Archaeology at Columbia University in New York, contextualises the current situation in Iraq after the events of the last three decades. All offer their thoughts on the significance of the destruction and on current responses, and discuss ideas for the future.

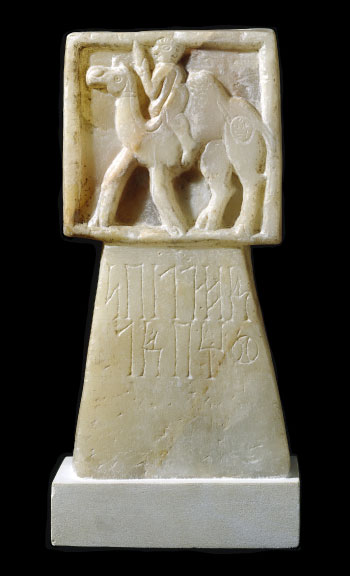

The kingdoms of ancient southwestern Arabia were separated by desert from the commercial centres of the Roman and Parthian Empires and never conquered by either power, yet connected with both as the source of several precious commodities – most importantly frankincense and myrrh – and as a conduit for many others by way of Indian Ocean trade (8).

Prosperity led to flourishing artistic traditions that encompassed abstract and schematic forms alongside elaborate Hellenistic-style figures. Funerary and religious sculptures were carved in a distinctive translucent calcite alabaster or cast in bronze, such as the remarkable figure of a child Dionysos or Eros riding a lion (3) on loan from the Arthur M Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution. The journey continues along the caravan routes north to the kingdom of Nabataea and its capital, Petra, with spectacular sculptures (10), on loan from the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, that similarly reflect multiple artistic and religious traditions.

H. 14.8cm. W. 6.5cm. Beirut National Museum.

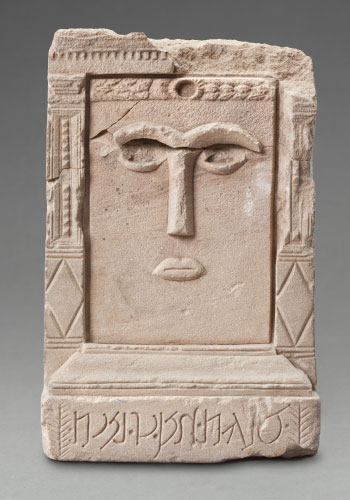

Graeco-Roman style busts of deities, such as Dionysos, were created alongside divine images that were highly schematic, such as a stele of a goddess with simplified facial features (2). One highlight is a fully reconstructed limestone arch (over eight feet high) that formed part of the Nabataean sanctuary at Khirbet et-Tannur in Jordan, with the cult statue of a god inside, on loan from the Cincinnati Art Museum and restored by conservators from both institutions in a collaborative project. The exhibition also takes the opportunity to reunite the Cincinnati sculptures with others from Khirbet et-Tannur on loan from the Department of Antiquities of Jordan.

In the gallery devoted to Judaea, astonishing objects on loan from the Israel Antiquities Authority include the Magdala Stone (6), renowned for its imagery relating to the Temple of Jerusalem and dating to the 1st century, during a time when the Temple still stood, before its destruction under the Romans in AD 70. The stone was discovered in an ancient synagogue at Migdal (Magdala) excavated in 2009.

Other objects movingly evoke Jewish struggles against Roman rule. A bronze statue of the emperor Hadrian (r 117–38) discovered in a Roman military camp at Tel Shalem is a powerful visual reminder of his suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt, named after its leader Simon Bar Kokhba, which was one of the largest and most serious rebellions against Rome. Bronze and glass vessels, a mirror, a knife and a key on display next to Hadrian's statue are personal effects that were hidden by people as they tried to escape from the Roman army during the Bar Kokhba revolt, seeking shelter in the Judaean Desert in a cave, named the 'Cave of Letters' after the documents found there. These extraordinary objects connect us poignantly to the fugitives.

The thriving Phoenician port cities of Tyre and Sidon and the colossal sanctuary at Heliopolis-Baalbek, located in present-day Lebanon, are the next stops on the journey. During the Roman period, Tyre and Sidon's harbours were expanded with breakwaters built using concrete, and the cities grew wealthy as exporters of incense, cedar and wine across the Mediterranean, and as importers of goods such as linen, jewels and silk from Judaea, Syria, Central Asia, India and China. During this time glass-blowing was invented and luxury vessels were produced in both cities and traded widely all across the Mediterranean. A 1st-century AD Roman blue glass flask on display (7) is one of the finest examples of the work of the Ennion, the most renowned and perhaps the first major maker of mould-blown glass.

Worshippers came to the sanctuary at Heliopolis-Baalbek, located in the Beqaa Valley, to venerate Jupiter Heliopolitanus, a powerful god of agricultural fertility and the cosmos. Architectural sculpture, photography, and reconstruction drawings illustrate how the sanctuary's innovative design combines ancient Middle Eastern and Graeco-Roman features, giving a sense of its immense scale.

Gilded bronze statuettes and stone sculptures on loan from the Beirut National Museum and the Musée du Louvre that depict Jupiter Heliopolitanus and his companion deities, Venus Heliopolitana and Mercury Heliopolitanus, reveal how Roman and ancient Middle Eastern religious practices were intertwined, and are probably based on the large-scale cult statues that originally stood in the temples.

A bronze statuette of the goddess Aphrodite Anadyomene discovered in Baalbek from the collection of the Beirut National Museum is a particular highlight. The figure appears in the pose of a famous Hellenistic statue type (4), but the gold earrings and a gold and emerald necklace she wears reflect the typically ancient Middle Eastern practice of adorning divine images.

This is also apparent in an alabaster statuette of a goddess wearing gold jewellery and with ruby inlays in her eyes and navel, discovered in Babylon (5). Despite its fame as a cosmopolitan city that played a key role in trade between the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea, the art of Palmyra remains relatively little known beyond specialists. Immense wealth spurred the city's development between the 1st century AD and the late 3rd century, when the Roman emperor Aurelian sacked the city, ending the reign of Queen Zenobia (AD 240–274).

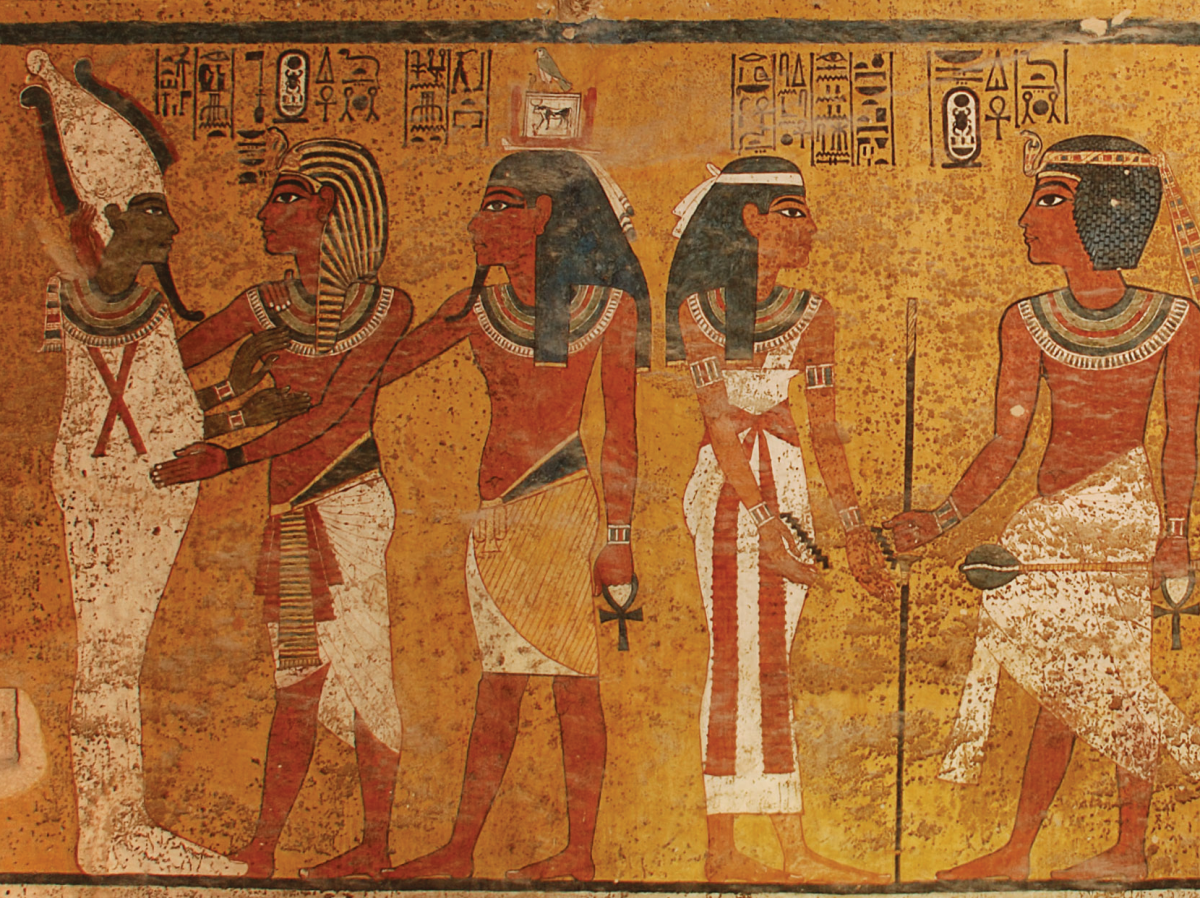

The World between Empires offers an exceptional look at how the funerary portraits that commemorated the city's elite and sculptures of its remarkable gods act as powerful expressions of a distinctive ancient Palmyrene identity (1), and enhances our understanding of the losses that occurred during attacks by ISIS in 2015 and 2017, including the destruction of the city's main religious building, the Temple of Bel, with explosives.

These acts took place alongside executions of local residents, including the murder of Khaled al-Asa'ad, the retired Director of Antiquities at Palmyra, on 18 August 2015, due to his refusal to co-operate with ISIS as he tried to save objects in the Palmyra Museum from destruction. Tadmor, the modern town located next to the archaeological site of Palmyra, has been extensively damaged, and its inhabitants have been displaced.

The section of the exhibition that focuses on the town of Dura-Europos (9) in eastern Syria reveals how religious life functioned within a cosmopolitan community in the ancient Middle East, as Jews, Christians and polytheists lived and worshipped in close proximity. A house, repurposed in about AD 232 as a space for Christian worship with an assembly hall and baptistery, is considered to be the world's oldest surviving church and contained wall-paintings with the earliest known images of Jesus, which are on loan to the exhibition from the Yale University Art Gallery.

The synagogue, also dated to the 3rd century, is famous for its wall paintings of biblical scenes that revolutionised scholars' understanding of early Jewish art as including figural imagery. Both were located in the vicinity of multiple temples where various gods of different origins were worshipped. Moving to the present day, looting at Dura-Europos has been extensive in recent years during the ongoing civil war in Syria, and photographs on display illustrate how satellite imagery is used to document the damage at the site, which remains largely inaccessible to archaeologists and cultural heritage specialists.

H. 33cm. W. 44.5cm. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven. Image © Yale University Art Gallery.

Travelling on from Syria to ancient Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq), the Parthian kings made their main royal residence at the city of Ctesiphon on the Tigris River. Mesopotamia was very rich agriculturally, and also the meeting-point between overland trading routes running across Syria and those through Iran and Central Asia, and between them and maritime trade via the Persian Gulf.

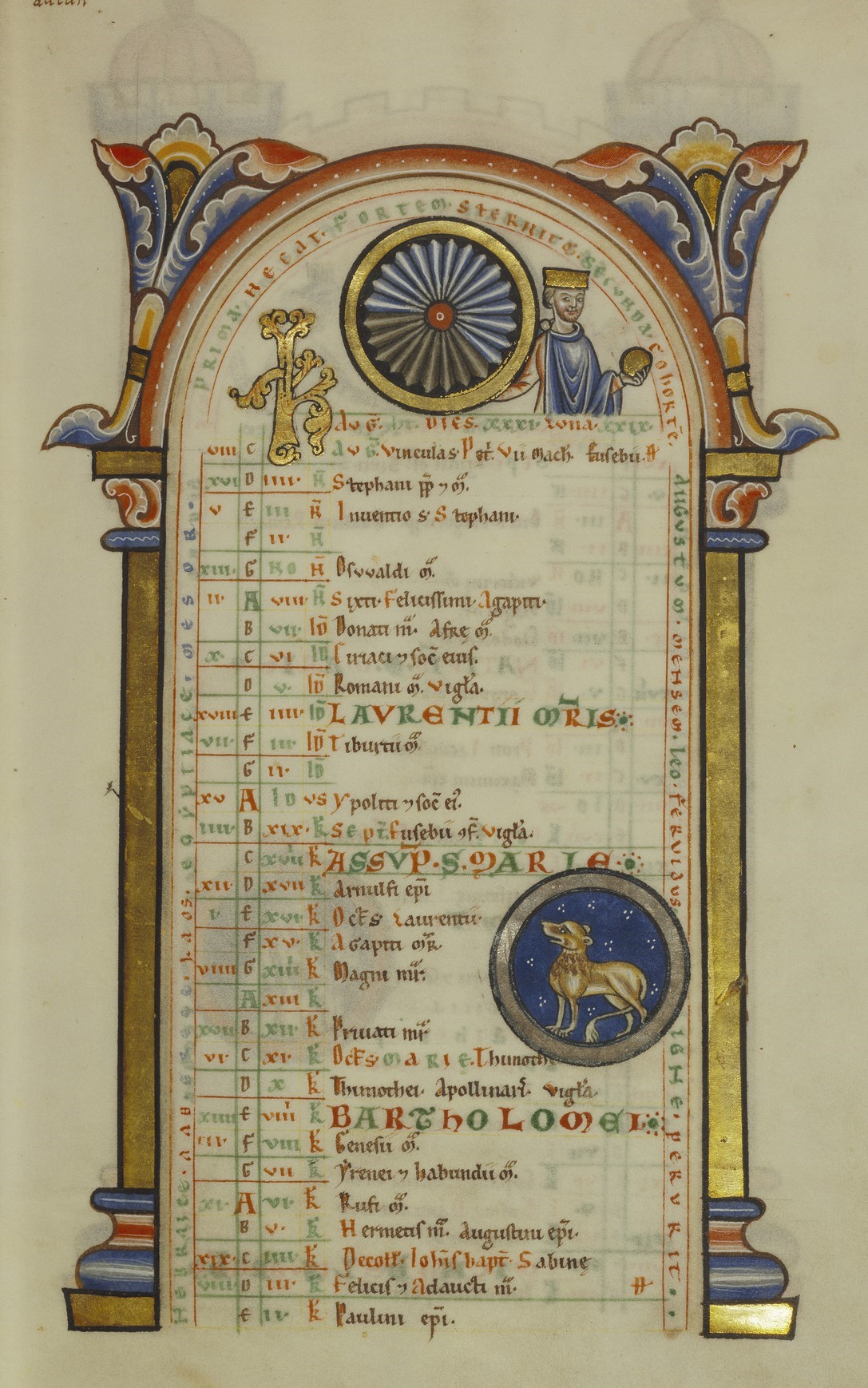

Northern Mesopotamia played a major role in the Parthian Empire's regional security and its control of long-distance trade routes. The city of Hatra not only acted as an important political and religious centre, but also effectively controlled trade along a major land route at the western end of the Silk Road. In southern Mesopotamia, ancient cities underwent fundamental changes during the Seleucid and Parthian periods. Temples that had functioned for thousands of years in cities such as Babylon, Nippur and Uruk entered their final phases as older urban landscapes were reconfigured, while new cities, above all Seleucia on the Tigris and Ctesiphon, took political primacy. Tablets on show in the exhibition show Babylonian texts being copied into Greek shortly before the cuneiform writing system became extinct.

For more than 250 years the balance of power between the Parthian and Roman empires defined the political map of the Middle East. By the middle of the century the Parthian Empire had ceased to exist and the Roman Empire had fractured, and a new power now controlled much of the Middle East: the Sasanian Empire, established by Ardashir I (r 224–41), a local ruler from Pars in southern Iran who had rebelled and ultimately overthrown the last Parthian kings, and almost drove Rome out of the Middle East.

The exhibition ends with a single object that is a visual expression of the political changes that occurred in the Middle East during the 3rd century: an extraordinary cameo featuring the Sasanian king, Shapur I (r 240–271), grasping the Roman emperor Valerian by the wrist, on loan from the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The World between Empires shares an in-depth exploration of the art, religions, history and culture of a period illuminated by recent scholarship, bringing together the stories of different cities across the ancient Roman and Parthian Middle East and their inhabitants through the theme of identity. Contextualising the recent destruction of cultural heritage alongside the ancient material, the exhibition aims to show why the archaeology and ancient art of this region are so important. Above all, it illustrates the variety and richness of the art of the ancient Middle East, and the many ways in which it connects us with real lives two millennia ago.

• The accompanying book by Blair Fowlkes-Childs and Michael Seymour is published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art (distributed by Yale University Press) in hardback at £45 ($65).