Memories of Antiquity - the ancient world through medieval eyes

Dominic Green gives us a preview of an exhibition about to open at the Getty Center in Los Angeles that shows us how the ancient world was viewed through medieval eyes.

'Lecturing at Hamburg University in the winter of 1927, the art historian Aby Warburg concluded his reflections on the Nachleben der Antike, the 'afterlife of Antiquity', with an image from the modern age of telegraphy and radio. He characterised Jacob Burckhardt and Friedrich Nietzsche, the rationalist historian and the wayward philosopher, as 'receivers of mnemonic waves'. Both, Warburg said, had been 'sensitive seismographs', receptive to images from 'the region of the past'.

At the time, Warburg was working on his Bilderatlas, or Picture Atlas. He wanted to map the bewegtes Leben, the 'life in motion' of images, from Antiquity to Christianity, and thence to the threshold of the technological

present, the Italian Renaissance and 17th-century science. By the time of his death in 1929, Warburg had assembled 63 complete sets of images, 17 incomplete sets that were still in progress, and some 1300 images; he may have planned as many as 200 wooden panels on which the images would be pinned.

The polymathic scholars who followed him, notably Erwin Panofsky, Fritz Saxl and Ernst Gombrich, traced how the clarity of ancient images varied with the quality of the transmission. The signal's strength could be weakened by cultural decay, as in the decline of oratory when Rome turned from republic to dictatorship. It could be strengthened by a fortunate conjunction of stability and patronage, as at the court of Charlemagne. It could be lost entirely for generations, silenced by barbarian invasion. It could even, as Warburg's hapless nephew Eddie discovered during a five-hour one-to-one lecture on 'Why England Sits in the Position of Neptune on the Pound Note', take surprising modern forms.

One result of their work is that definitions of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance have become, as the scholars like to say, 'problematic'. Both terms are from the 19th century. The idea of a benighted 'Middle Ages' between the fall of Rome and the rise of the modern state was coined in the 1830s by the French historian and liberal politician Jules Michelet. The identification of the Italian Renaissance with Machiavellian politics and secular 'egotism' derives from Burckhardt's The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860). But was the image of Antiquity ever lost completely, to be rediscovered in the city states of 14th-century Italy?

The standard narrative that most non-specialists have is an old chestnut,' says Kenneth Lapatin, co-curator of Remembering Antiquity, the J Paul Getty Museum's new exhibition on the medieval view of ancient images. 'It's a gross oversimplification to say that there was a Dark Age, that Antiquity and the great achievements of Classical civilization were lost, that a few monasteries preserved a little of it, and then Antiquity was rediscovered in the Renaissance in Italy.' And did the secular revival of Ancient character as Modern personality really reappear for the first time in Florence?

In 1873, little more than a decade after the publication of Burckhardt's thesis, the English aesthete Walter Pater, chiefly remembered these days for being Oscar Wilde's tutor, argued that the 'outbreak of the human spirit may be traced far into the Middle Age itself', and gave the 'Italian' Renaissance origins in late 12th-century France. Boccaccio, Pater wrote, 'borrowed the outlines of his stories from the old French fabliaux [bawdy tales]', and Dante 'expressly connects the origin of the art of miniature painting with the city of Paris'.

Today, scholars are more likely to trace the sequence of transmission to Panofsky in the title of a 1944 article, Renaissance and Renascences. The Italian Renaissance was not created out of nothing, like St Augustine's notion of the Creation as creatio ex nihilo. Nor was knowledge of Classical literature previously equated with the perceived values of Classical paganism, or of humanism, the modern cultivation of a secular worldview. We might adopt the more limited definitions of the Byzantinist scholar Warren Treadgold: a Renaissance is 'any revival of knowledge of Greek and Latin literature', and a Dark Age is any period that sees 'a setback to such knowledge'.

'There were a whole series of different renaissances,' explains Lapatin. 'Antiquity was not forgotten in the Middle Ages.' In the 4th century AD, the Hellenic or Second Sophistic age immediately followed the decline of Greek and Latin letters. The revival of Latin scholarship in the 8th-century 'Northumbrian Renaissance' through Anglo-Saxon scholars like the Venerable Bede laid the ground for the 'Carolingian Renaissance' at the court of Charlemagne. In the '12th-century Renaissance', political stability, economic growth, and the cumulative effect of monastic scholarship combined to produce both an intensification of Latin translation, and the growth of vernacular language in letters and architecture.

'Antiquity was constantly being invoked, modelled, transformed and reinvented in a variety of ways that didn't necessarily correspond to what the Renaissance has become, which is identified with naturalistic presentation of the human form,' Lapatin argues. 'In history, science, technology and even formal imagery, whether it's iconographical or the case of Nike figures becoming Christian angels, Antiquity is constantly being evoked and used for new purposes. The idea of this exhibition is to show some of these different phenomena.'

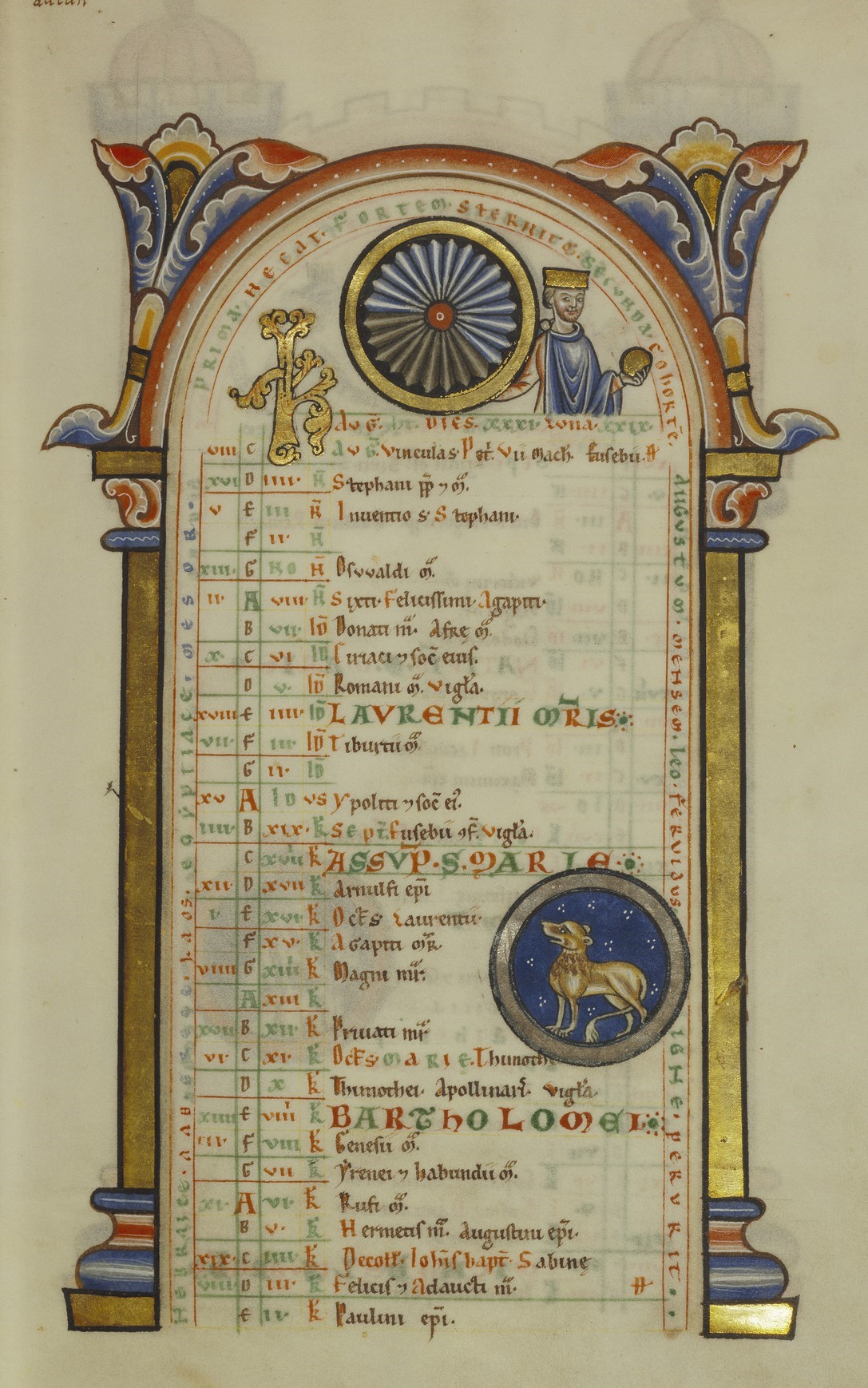

Lapatin's co-curator, Kristen Collins, explains: 'The introductory wall encapsulates the show's overriding theme of repeated engagement with the Classical past, using four historical moments. Our designers have placed the groupings of ancient and medieval objects within painted colonnades on the wall. This allows visitors to contemplate a moment of Hellenic Renaissance in Late Antique Egypt separately from the Carolingian Renaissance or the 12th-century Renaissance.'

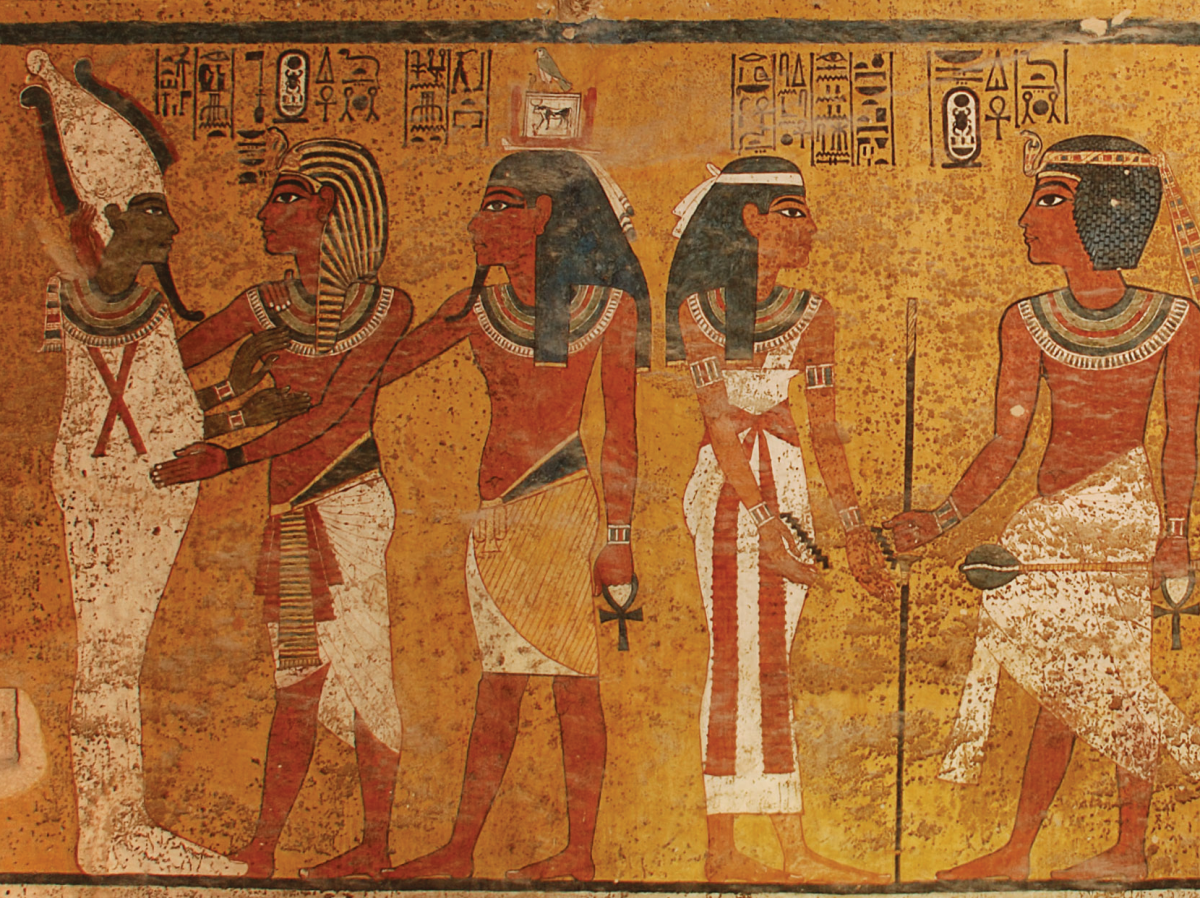

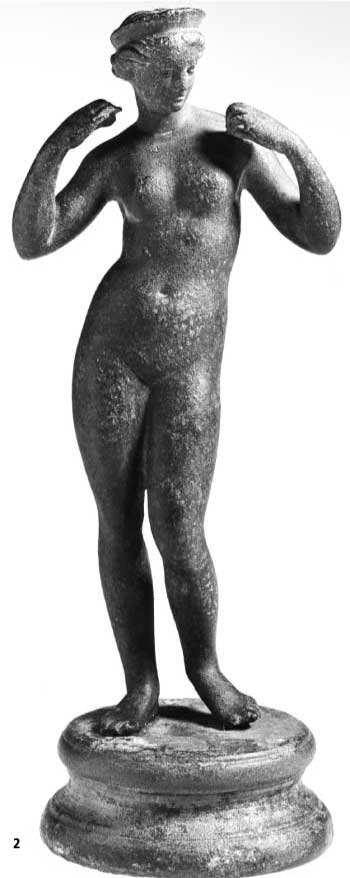

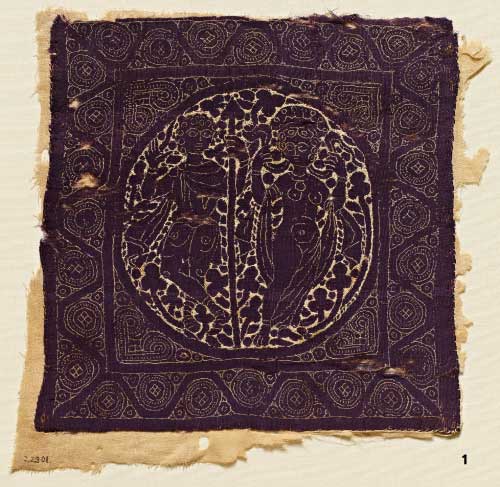

A textile (1) circa AD 400, excavated at Illahun, near Fayum in Egypt, shows Venus and a male, possibly Aeneas or Mars. This is paired with a small bronze statuette of a 1st-century AD Venus (2) in the same pose, which was purchased by J Paul Getty in Paris in 1957.

'The textile probably came from a gravesite,' explains Collins, who is also Getty's Curator of Manuscripts. 'It shows that Late Antique Egypt had a period of retrospection, of looking back to Greek myth and poetry. You have patrons who are potentially Christian, but who nevertheless would buy luxury goods with these antique motifs.

'It suggests that there wasn't a conflict between these two cultures, but that there was an overlay, and an appreciation for the past, even as you cross over from the multiple religions of Antiquity into Christianity. We have created key groupings of encounters between Medieval and Ancient throughout the exhibition.'

In The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, Burckhardt wrote: 'Great was the influence of the old writers on the Italian mind in the 14th century and before, yet that influence was due rather to the wide diffusion of what had long been known, than to the discovery of much that was new.'

The Italian scholars of the 14th century did not describe themselves as working in a Renaissance, or 'rebirth', but in the Scienza Nuova (New Knowledge). Yet mediaeval scholars did describe their work as renovatio, the renewal of civilisation by recourse to ancient precedents.

'In these disparate cultures, renovatio meant different things to different people,' Collins says. 'For the Carolingians, the idea of a renewal of the Roman Empire meant administrative strength and a religious connection to contemporary Rome. But in the 12th century, renewal involved a period of intense interest in Ancient texts, and the translation into Latin of Greek texts that had been preserved in Arabic.

'The age of scientific discovery that we associate with the Renaissance proper would not have been possible without access to Greek texts on optics that had long been preserved by the manuscript culture of the Arabic world. In the 12th century, we see this information cycling back to the West.'

Mediaeval renovatio occurred within the political framework of the nascent Latin kingdoms of western Europe, and within the eschatology of Latin Christianity. In some cases Lapatin points out, there is a parallel of visual forms. Graeco-Roman images of Nike, the winged victory, are transformed into angels, or serve as icons. Indeed, the English word 'angel' derives via Latin from the Greek angelos (messenger). A hovering pair of gold and glass earrings (3) with pendant Nikai (circa 225-175 BC) seem not to be aware of their future metamorphosis into messengers of monotheism.

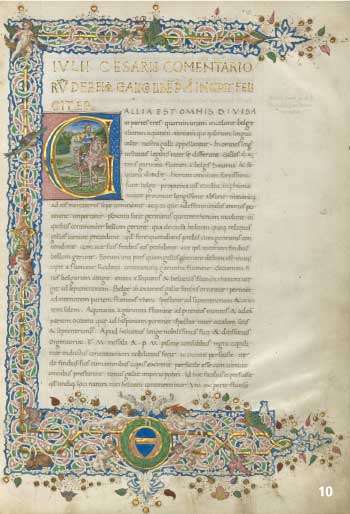

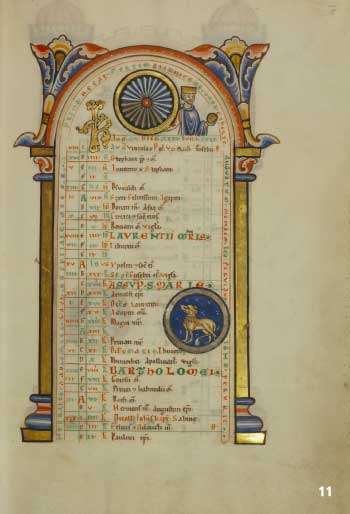

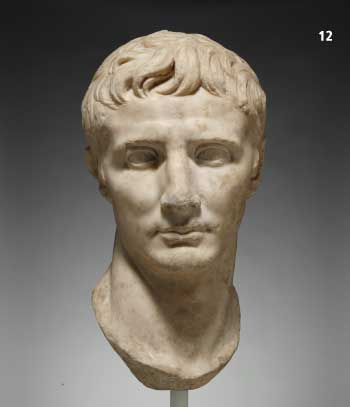

There are also changes of both form and function. As in the early Christian blurring of the portrait of Jesus with the image of Constantine the Great, Julius Caesar (10), Augustus Caesar (12) – whose natal chart is also on show (11) – and Alexander the Great are all depicted as world rulers in medieval garb.

An intriguing sequence of exhibits traces the afterlife of the image of Alexander, and how an image of divinity from 'the region of the past' was translated into another for the medieval present.

First, we encounter a Hellenistic marble statuette of Alexander (7), dating from the 2nd century BC, which J Paul Getty acquired in London in 1973, the year before his death. There is also another familiar image of Alexander, with the horns of his divine father, Zeus Ammon, on a silver Greek tetradrachm (4) minted by his general Lysimmachus. Nearby, there is a bronze statuette of a winged griffin with an Arimasp (8), one of the mythical one-eyed Scythians who, in ancient myths, struggle for the griffins' gold. In a legend from Syria, Alexander caught a pair of griffins, caged them and trained them with hunks of raw beef. He then used their wings to fly him on a seven-day tour of his empire.

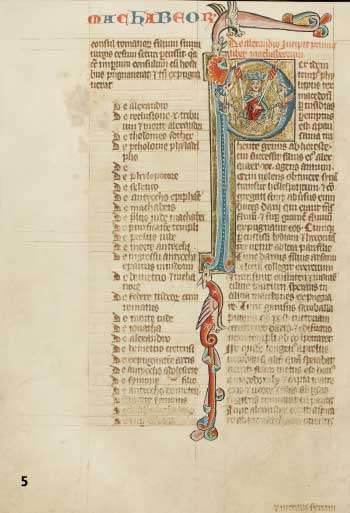

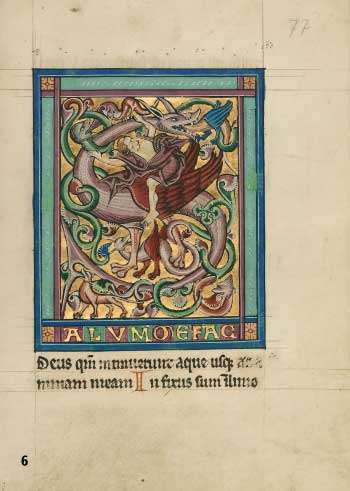

Next, we see a medieval image of Alexander's griffin-powered ascent, a story which appealed to the bestiary-drawing medieval mind. In Alexander the Great Carried Aloft by Griffins, an illuminated manuscript leaf (5) from Peter Comestor's 12th-century Historia Scholastica (Austria, circa AD 1300), Alexander rises in rich tempera and gold. In a second manuscript image (6), Alexander travels from one myth to another, and one conception of empire to another, as the pagan Greek takes on the lineaments of Jesus.

'When comparing this image to the common iconography of Christ's ascent into Heaven,' Collins says, 'you can see how these figures become blended in the Middle Ages. There's an appropriation of Alexander for a new Christian story and paradigm.'

The Greekness of Alexander was mediated at second or third hand in the mediaeval period, and the language of Alexander quite lost.

Petrarch, Burckhardt noted, 'owned and kept with religious care a Greek Homer which he was unable to read'. Yet some kinds of knowledge were never lost, especially when they were mediated through Latin. 'Pliny never disappeared throughout the Middle Ages,' Collins points out. 'He is mined by Isidore of Seville, he's in the bestiaries, he is in Vincent of Beauvais' Speculum Maius.' Vincent of Beauvais (circa 1190-1264), a Dominican monk, compiled Speculum Maius, a three-part, encylopaedic synthesis of Latin sources, between 1244 and 1260.

'The ancient writers travelled into Christian compilations which presented the history of the world from the Creation until the medieval present. They didn't separate ancient from Christian or Biblical history as clearly as we might do.'

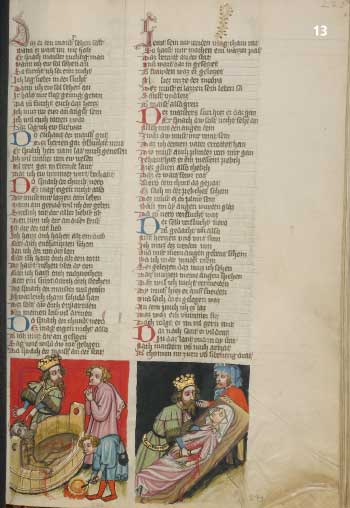

A pair of manuscripts showing images of Nero illustrate two different distortions of the historic image. 'In the first,' Lapatin says, 'the Nero who has killed his mother and orders the death of Seneca is made even more evil.' In a Bavarian edition of Jans Enikel's Weltchronik (World Chronicle), illuminated circa 1400-10, Seneca (13) does not kill himself, but is murdered by Nero – a more personal, more medieval assertion of power.

The second manuscript comes from Book VI of St Augustine's City of God, in an edition illuminated in France by the 'Master of the Oxford Hours', circa 1440.

'Although Augustine belittled the ancient mythology, he was nonetheless very well read in Ancient history and culture,' Lapatin says. 'In the manuscript, Marcus Varro is depicted sitting in Augustine's study, (14) like a contemporary scholar. There's an awareness of the passage of time, less in terms of breakage than continuity.'

The J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Augustine managed to find monotheistic precedents for Christian theology in the works of both Varro and Seneca. 'There was no monolithic understanding of Antiquity in the Middle Ages,' Collins says. 'There were constant iterative engagements with the possible ways in which the past was used and understood in the

mediaeval present.'

The afterlife of the images does not undermine the importance of the Italian Renaissance, so much as elucidate the historical processes that preceded it, and on which it drew. 'There is continuity, and also disjunction and invention,' Lapatin concludes. 'This is very much a show for the visiting public. It's a teaching opportunity, to show the public the many levels of engagement with the cultural past. The Classical past never went away.'