The Golden Pharaoh - the story of the ancient Egyptian boy-king

As the latest Tutankhamun exhibition prepares to open in London, Jaromir Malek tells the story of the ancient Egyptian boy-king whose serene face has haunted us for almost 100 years.

Like Egyptophiles all over the world, Londoners love Tutankhamun and it is clear that he enjoys coming back: Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh will open on 2 November. Those of us old enough can still remember the huge queues of people (over 1.6 million visitors) patiently waiting to see the magnificent Tutankhamun exhibition at the British Museum in 1972. Later on, a selection of artefacts from the boy-king's tomb were put on show in the Millennium Dome in 2008 and, now, 150 of his treasures (some of them leaving Egypt for the first time) are to be exhibited at the Saatchi Gallery.

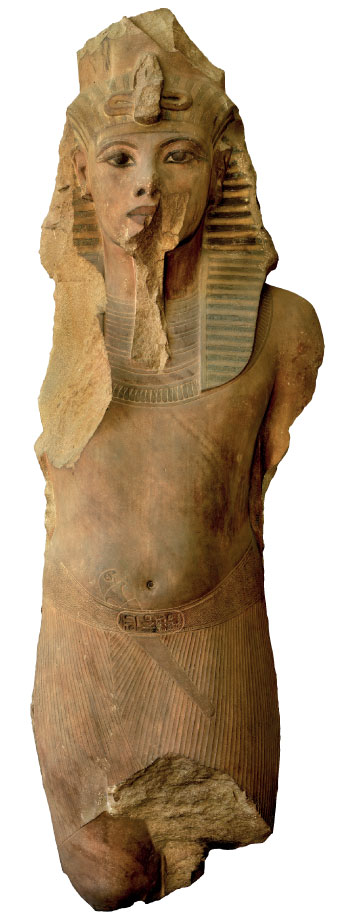

H. 285cm. Medinet Habu, Temple of Ay and Horemheb. © Laboratoriorosso, Viterbo/Italy.

Having already been on show in Los Angeles and Paris, this exhibition is on a world tour stopping off in a total of 10 cities. But why now? There are two reasons: the first is the forthcoming centenary of the discovery of the tomb; the second is the transfer of Tutankhamun's objects from the old and beautiful, but no longer adequate, old Egyptian Museum at Midan Tahrir in the centre of Cairo to the new Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) at Giza, not far from the Great Pyramid. The official opening of the new museum is expected to take place in 2020. Then, for the first time, nearly all Tutankhamun's objects will be displayed there, permanently.

The three things connected with ancient Egypt that immediately spring to the minds even of people who are not particularly interested in the past, are the Pyramids, the Sphinx and the tomb of Tutankhamun. The pyramids are mind-boggling pieces of engineering which even these days present a challenge because of the precision of their construction and the complexity of organisation connected with it. The riddle of the Sphinx continues to amuse but the main appeal of the tomb of Tutankhamun lies in its fabulous riches and the fact that it survived almost intact for several millennia. For many, the boy-king's face embodies ancient Egypt, and it would be wrong to dispute it, however biased and limited this notion may be.

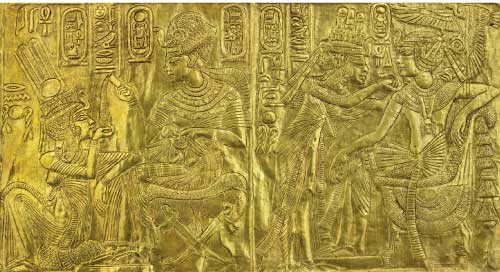

L. 33cm. W. 17cm. H. 24cm. Valley of the Kings, KV62, Antechamber. © Laboratoriorosso, Viterbo/Italy.

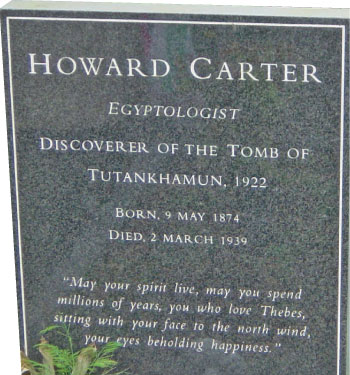

The discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, and the subsequent recording of its contents, is primarily due to one man – Howard Carter. He was born in London, on 9 May, 1874. His family came from the market-town of Swaffham in Norfolk, where Howard spent his early life. His father was an accomplished artist and his son, who had limited formal education, inherited his skills as a painter.

But it was a sheer chance that Didlington Hall, the residence of William Amhurst Tyssen-Amherst (1835–1909), later Lord Amherst, a keen collector of Egyptian antiquities, happened to be close to Swaffham. He probably met Howard in connection with his father's painting commissions and so became aware of the young man's artistic talent. William was acquainted with Percy Newberry who was in charge of the copying of tomb paintings at Beni Hasan in Middle Egypt on behalf of the London-based Egypt Exploration Fund. And when the need arose for another copyist, it was Howard Carter whose name was mentioned and who was chosen. He left Norfolk and arrived in Egypt in 1891 aged only 17.

Carter learnt his Egyptology on the job. He was very much a self-made man, with all the advantages and drawbacks this entailed. In 1893 he was transferred to work on another project, the recording of reliefs in the temple of Queen Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri. Six years later, he was appointed Chief Inspector of Antiquities in the Egyptian Antiquities Service.

One of the areas for which he was responsible was the Valley of the Kings. Of this he became especially enamoured and acquired a detailed knowledge of it. But all this came to an end in 1904 when as the

result of a reorganisation in the Antiquities Service he was posted to the north, to the inspectorate of Lower Egypt. This made him intensely unhappy and culminated in 1905 in an incident in the Serapeum at Saqqara during which the behaviour of a group of rowdy European tourists was challenged by Egyptian employees of the Antiquities Service. They received more than abuse from the unruly, but influential, visitors. Carter's sympathies were, however, unequivocally with the local men. This led to his resignation from the Service.

Several lean years followed but, in 1909, an event occurred which put him on the road to the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun. It was then that Carter met someone without whom this momentous event would never have happened. George Edward Stanhope Molyneux Herbert, the 5th Earl of Carnarvon (1866–1923), an English aristocrat who originally came to Egypt to aid his recuperation following a car accident, became so enamoured of ancient Egyptian antiquities that he began to finance excavations, eventually involving Carter. Carter would have preferred to work in the Valley of the Kings but permission to do this was not granted until 1914.

Once back there, Carter set about looking for a significant discovery, ideally a new royal tomb. But there was no way of deducing where this might be or, indeed, if there was one. He relied on his detailed knowledge of which parts of the Valley of the Kings remained unexplored but, ultimately, as is almost always the case in archaeology, it was luck which led to his stunning discovery.

Early on in the 1922-3 campaign, on 4 November, 1922, the first step of a staircase which appeared to lead to an unknown tomb was discovered and, when a sealed doorway was exposed the following day, Lord Carnarvon was summoned back to Egypt. In his presence, on 26 November, a small opening was made in a second doorway which had the cartouches of Tutankhamun impressed on it. Carter was the first to get a glimpse of the room (later known as the Antechamber) beyond it. It is on record that in reply to Carnarvon's question 'Can you see anything?' he allegedly uttered the now immortal words, 'Yes, wonderful things' (although this may be an edited version of what was actually said).

The tomb of Tutankhamun was the only royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings which was found substantially intact. It contained a collection of well-dated, contemporary items, some of them unique. They are mostly well-preserved and can be studied with ease.

Their meticulous recording and conservation took Carter a decade, between 1922 and 1932. During this time he assembled a small team of first class specialists to help him. His good relationship with Egyptologists from the Metropolitan Museum in New York was extremely useful. The British Egyptologist Arthur Mace (1874–1928) was Carter's second-in-command, Harry Burton (1879–1940) from the Metropolitan was responsible for photographing the tomb and its contents. Alfred Lucas (1967–1945) of the Egyptian Survey Department took care of the conservation of the artefacts and Carter's old friend, Arthur Callender (1876–1936) looked after the practical aspects of the clearance of the tomb. Several other Egyptologists including AH Gardiner (1879–1963), Percy Newberry (1869–1949) and James Henry Breasted (1865–1935) – all helped with specific specialised tasks.

The care and expertise with which the contents of the tomb were recorded impress us even today. Serious difficulties had to be tackled during the work. The nature of the discovery aroused huge public interest and the perhaps rather injudicious handling of the press caused Carter and his team endless problems. Egypt was also going through great political changes, and the relations with authorities and with the Antiquities Service which directed all archaeological work in the country reflected this.

Sadly, Lord Carnarvon who had sponsored the excavation, died as a result of blood poisoning in April 1923 – this gave rise to the popular myth of the persistent 'curse of the pharaoh'. Fortunately, and most generously, Lord Carnarvon's widow, Almina Herbert (1876–1969), continued to finance the work in the tomb, even though it was becoming clear that its contents would not be shared with the excavators. Practices in Egyptian archaeology were changing.

But who exactly was this golden boy-king? Originally he was named Tutankhaten and he reigned between 1336 and 1326 BC (note that several dating systems are in use and the dates given elsewhere may vary by up to 10 years), during the aftermath of the so-called Amarna Revolution during which the 'heretic pharaoh' Akhenaten (originally Amenhotep IV) abandoned traditional Egyptian beliefs in a multitude of deities in favour of the worship of one god, the sun deity, the Aten. This was a real religious revolution, a radical monotheism quite unprecedented in ancient Egypt – and never to be repeated.

Akhenaten (d circa 1336-1334) was Tutankhamun's father but the identity of his mother is still disputed. It may have been a minor queen but it is possible that it was Nefertiti herself. Also the precise circumstances which led to Tutankhamun's succession are not yet clear. Smenkhkare (d 1333 BC), his brother or half-brother, may have been Akhenaten's co-regent for a few years and there is also some evidence which suggests that for a short period of time, possibly after Smenkhkare's death, there was a female pharaoh, perhaps ruling as a co-regent.

During Tutankhamun's reign much effort was made to reverse the effects of Akhenaten's religious reforms, especially restoring the ideological and economic position of temples all over Egypt. Scenes on the walls of many which had been damaged during the previous years were now repaired. Akhenaten's new capital (named Akhetaten and, today, known as Amarna) in Middle Egypt, was abandoned in favour of Memphis. Fresh building projects were inaugurated and work on those left unfinished by Tutankhamun's predecessors resumed. Some of the items found in Tutankhamun's tomb bear the name of the Aten, as well as that of the god Amun, now restored to his pre-eminence.

In all this, the young king had to rely heavily on his powerful officials, among them General Horemheb who ascended the Egyptian throne and reigned circa 1319–1292 BC. From the examination of the mummy of Tutankhamun we know that the king was only about 18 years old when he died and from labels on wine-jars found in his tomb we can deduce that he reigned for eight or nine years. His death was almost certainly unexpected but the reasons for it, natural or accidental, are still disputed.

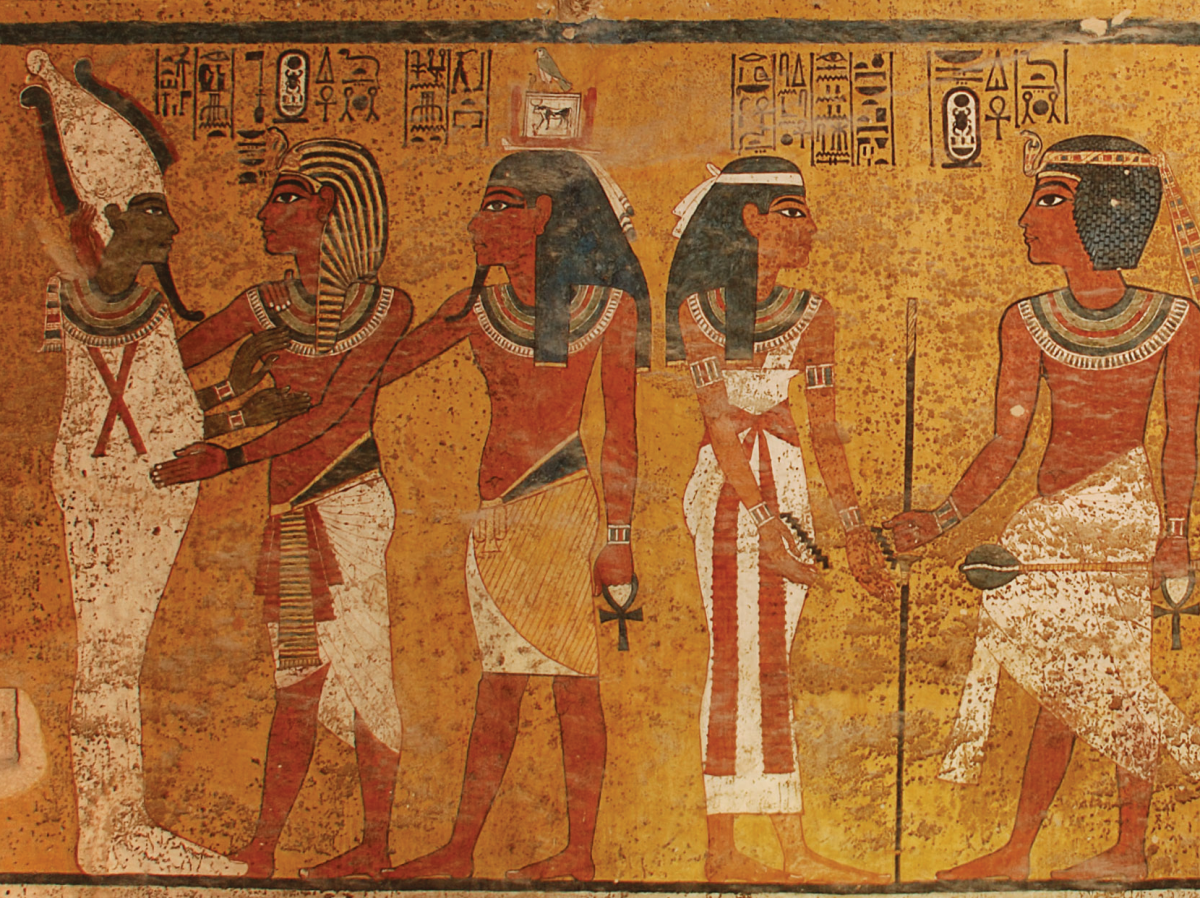

Royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings are made up of extensive underground galleries formed by a series of corridors and rooms but with no conspicuous entrances above ground. Mortuary establishments in which the cult of the deceased kings was maintained were situated further east, along the cultivation edge. But Tutankhamun's tomb is not of the standard design. It is very small and consists of only four rooms. The burial chamber, containing four wooden shrines over a quartzite sarcophagus with three coffins and the king's mummified body with the famous gold mask, was behind another sealed doorway, flanked by two standing statues of the king. A room connected to it held, among other things, a wooden shrine with a magnificent alabaster canopic chest containing the king's internal organs. Another store-room completed the plan of the tomb. Only the burial chamber was decorated with paintings; those on its northern wall show King Ay (r 1323–1319 BC), Tutankhamun's successor, performing a funerary ceremony for the deceased Tutankhamun.

Some anomalies on the surface of some walls, combined with the unusual and very simplified plan, have recently led to a suggestion by Egyptologist Dr Nicholas Reeves (b 1956) that this tomb, in fact, represents a part of another one from which it was disconnected when the king unexpectedly died without his own tomb yet ready for his burial. It has been mooted that the possible owner of the original tomb may have been Nefertiti. The theory has not yet been proved nor convincingly refuted. It is, however, worth mentioning that nearby there is a tomb of a similarly unusual plan which contained a male burial probably transferred there from Amarna. It is not impossible that Tutankhamun's tomb may have been converted from another also intended to contain an Amarna re-burial.

The contents of the tomb betray the haste in which the burial was conducted. There was a total of 5,398 objects, varying, in size, from very large to tiny, crammed into the tomb. Some of these had been used during the king's lifetime, others were made specially for the tomb, and some even represent objects originally intended for another tomb-owner and opportunistically used. The tomb was attacked by robbers not long after its closure but, before serious damage could be inflicted, the robbery was detected and order was restored by necropolis officials. The ultimate survival of the tomb was due to builders' debris from a later tomb nearby being dumped in its vicinity, combined with much sand, blown by wind and deposited by torrential rain – all of which hid the entrance.

Howard Carter died, aged 64, in 1939, without having time to produce a detailed publication of this astonishing corpus of material. His lasting contribution are three enthralling volumes The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, which were published between 1923 and 1933 (the first jointly with AC Mace).

It is worth mentioning, and it is a sobering thought, that probably about half of the material found in the tomb still awaits detailed scholarly study and publication. The reasons for this sad state of affairs are complex but to be

tackled urgently.

Carter's excavation records are now in the archive of the Griffith Institute, the University of Oxford. He died without direct descendant and this material was presented to the University of Oxford by his niece, Miss Phyllis Walker. His hand-written notes (about 3,150 of them) are on record cards measuring about 20.5cm x 12.5cm and there are some 1850 black-and-white glass negatives made by Harry Burton. Some of the cards also contain recordings made by Carter's assistants, in particular Arthur Mace and Alfred Lucas, as well as plans and sketches. Most of these records are now available on the Griffith Institute's website.

All black and white images © Griffith Institute, The University of Oxford.

The greatest wish of an ancient Egyptian was that, after their death, their name should continue to live on forever. There is little doubt that Tutankhamun has achieved this as the thousands of visitors who go to gaze in wonder at his treasures perpetuate his immortality. But how many remember the name of Howard Carter? Few people came to his funeral and he was buried in Putney Vale Cemetery in South London. His grave is now marked with a grey marble stone bearing an inscription from Tutankhamun's 'Wishing Cup': 'May your spirit live, may you spend millions of years, you who love Thebes, sitting with your face to the north wind, your face beholding happiness'.

TUTANKHAMUN: on show & in print

• Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh, presented by Viking Cruises, is on show at the Saatchi Gallery in London (tutankhamun-london.com) from 2 November until 3 May 2020.

• Tutankhamun: The Story of Egyptology's Greatest Discovery by Jaromir Malek is published in hardback by Andre Deutsch at £25.

• The Griffith Institute in Oxford (www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/discoveringTut) has initiated a series of publications in which objects from the tomb are studied and published. The latest is The Ornamental Calcite Vessels from the Tomb of Tutankhamun by Lise Manniche.

• Tutankhamun: The Original Photographs by Christina Riggs (with Rupert Wace) is published by Rupert Wace Ancient Art, in paperback, at £25 plus p&p (available to order from: [email protected]).

• Tutankhamun: The Discovery of a Forgotten Pharaoh will be on show in the Calatrava exhibition space in the Gare des Guillemins in Liege (www.europaexpo.be/toutankhamon) from 4 December to 31 May 2020.