Written in Gold

Some of the most significant texts from around the world have been given very special treatment, with words of holiness and of diplomatic value written both in and on gold. Annabel Teh Gallop, Eleanor Jackson, and Kathleen Doyle investigate the indelible importance of the precious metal in luxury manuscripts.

All images: © British Library

Gold speaks in a universal tongue and has long held a special place in manuscript traditions around the world. Throughout the centuries, it has been incorporated into books and documents in all sorts of ways: as golden writing, as inscriptions on strips of gold, in illuminated paintings, and in gilded book covers. So intrinsic was gold to the craft of luxury book production that manuscript decoration is known as ‘illumination’ from the use of gold to light up the pages. This relationship is at the heart of the British Library’s new exhibition, Gold: 50 spectacular manuscripts from around the world, which showcases 50 golden manuscripts in 17 different languages, from 20 countries, ranging in date from around the 5th century AD to the 1920s. It includes many of the finest items within the Library’s collection. Some of these are very well known, and may be familiar from publications or previous exhibitions, but there are many other no less exquisite manuscripts that have never been seen in a gallery setting before.

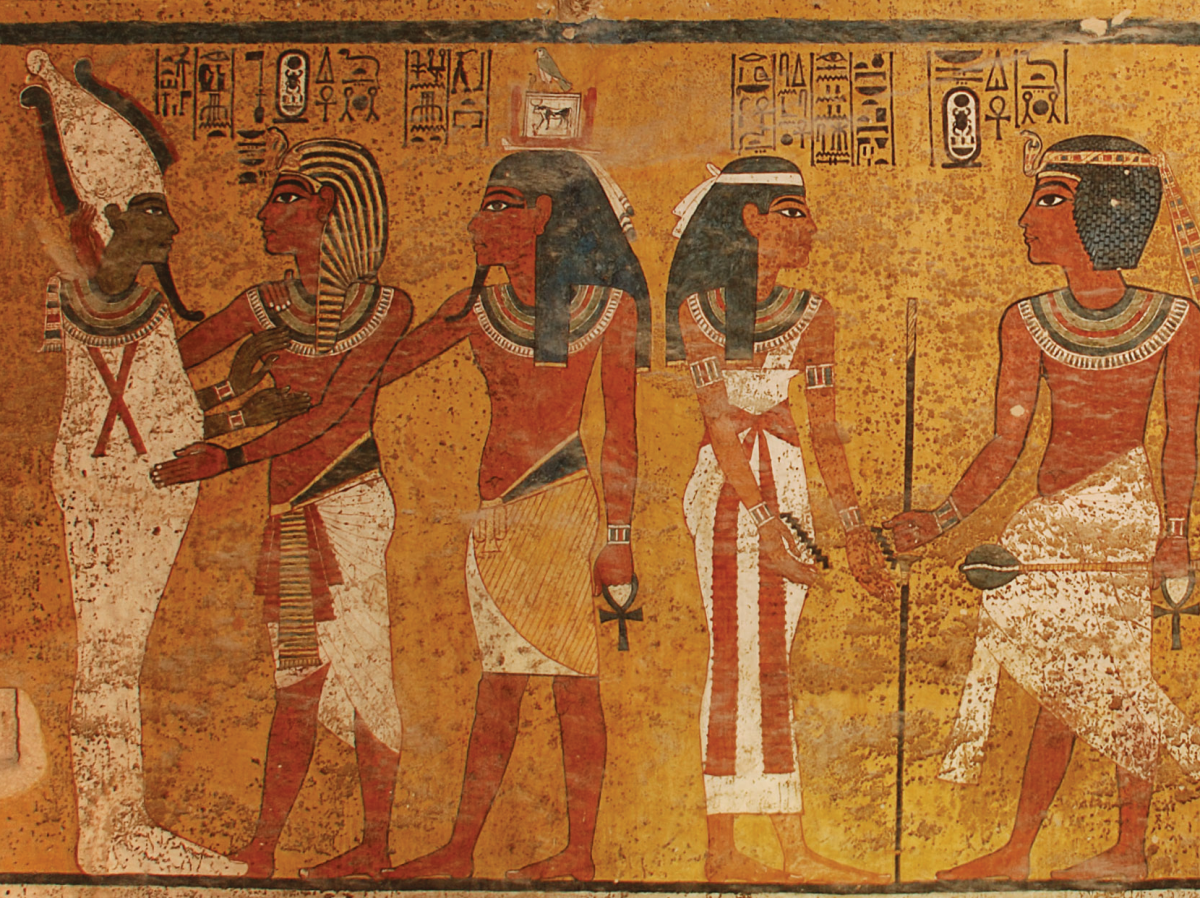

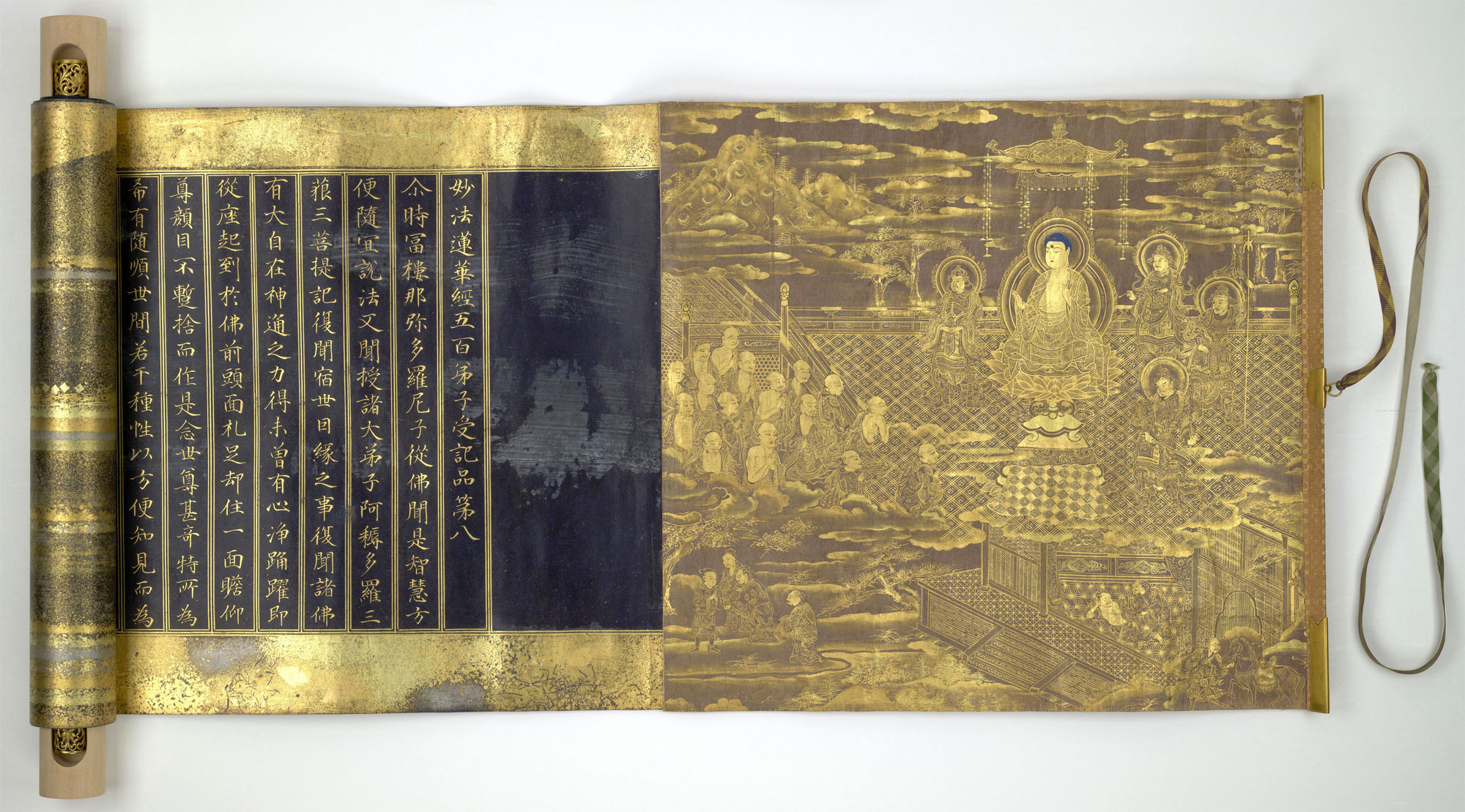

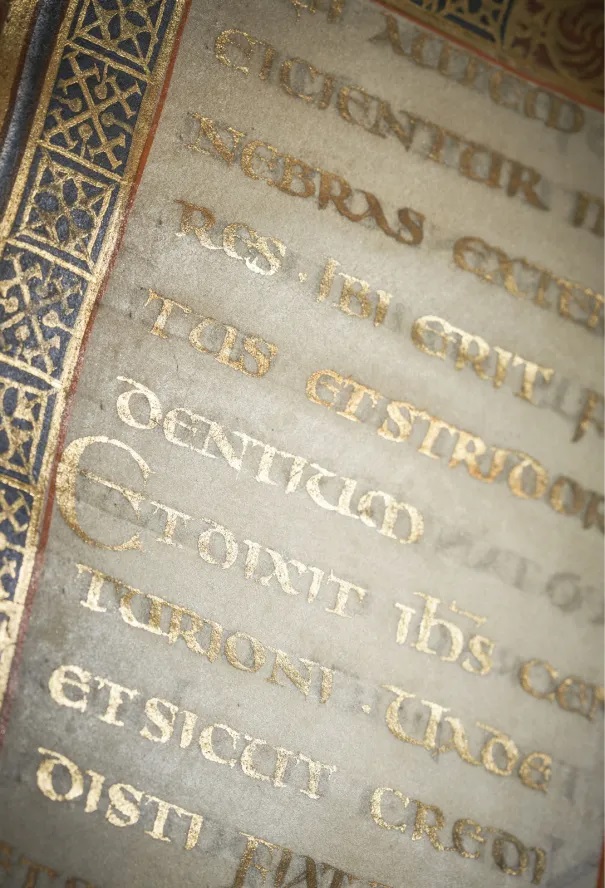

We open the exhibition with three sacred texts, representing three major religions, each illustrating perfectly how – across time and place – people wrote in gold to express the extraordinary importance of a text. The 9th-century Harley Golden Gospels – a copy of the Four Gospels, probably written for Emperor Charlemagne at his court in Aachen – is shown alongside one of seven volumes of a Qur’an commissioned by the Mamluk ruler of Egypt, Sultan Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Jashnagir, and completed in Cairo between 1304 and 1306. Between these two impressive books is another spectacular text: a lavishly decorated scroll from Japan, written in 1636 in gold ink on blue indigo-dyed paper, commissioned by the Emperor Go-Mizunoo for presentation to the Toshogu Shrine in Nikko. It contains the Lotus Sutra, one of the most influential scriptures of the Mahayana school of Buddhism in East Asia, and seen by many as the summation of the Buddha’s teachings. All three copies of holy scriptures, which are written entirely in gold respectively in Latin, Arabic, and Japanese, also contain beautiful painted illuminations – such as the depiction at the start of Lotus Sutra of the Buddha granting promises to his disciples that they may attain Buddhahood in their future lives – but in this exhibition we have chosen to focus attention on the golden text itself.

Just as gold was used in sacred contexts to evoke the awe and mystery of God, secular rulers also saw the potential of gold for conveying an impressive message. Royal documents were embellished with gold to both honour the recipient and reflect the wealth and stature of the sender, as well as to emphasise the text’s authority. Perhaps the most magnificent royal decree in the exhibition was issued by the Mughal emperor Shah ‘Alam II in 1789 to Sophia Elizabeth Plowden, bestowing on her the aristocratic rank of begum with the title Bilqis uz-Zaman, ‘Sheba of the Age’. The wife of an East India Company Officer, Sophia collected Persian and Hindustani songs at the Lucknow court, which she recorded in European musical notation and later published to great acclaim. The background of this great firman or decree written in Persian is entirely gilded, with religious phrases in Arabic at the top written in gold in ‘square’ calligraphy. The whole document was then mounted on a fine piece of red silk brocade almost two metres in height.

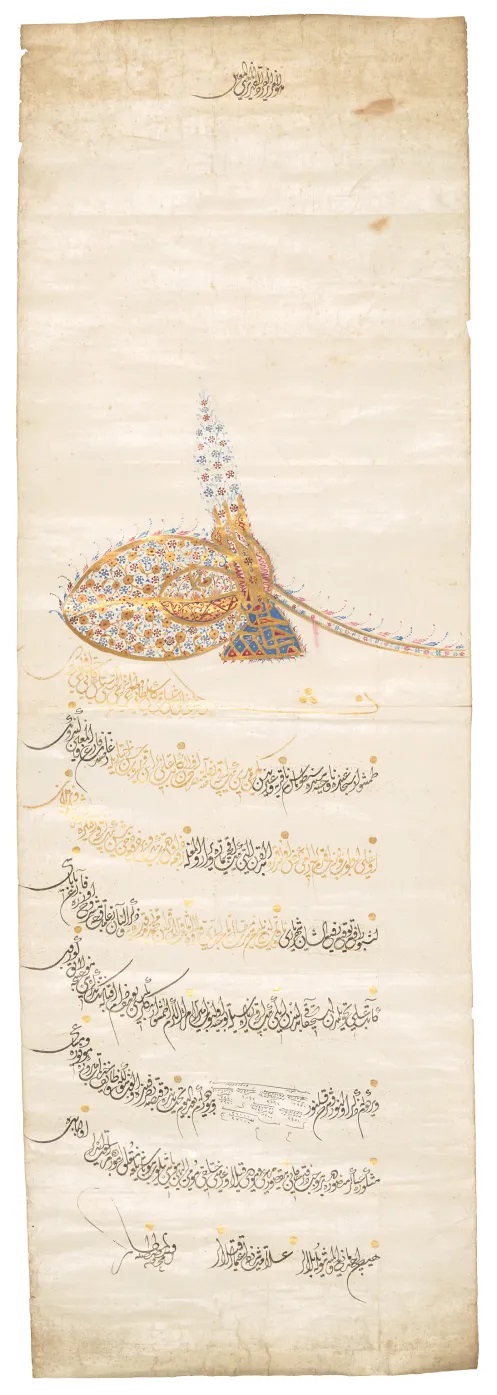

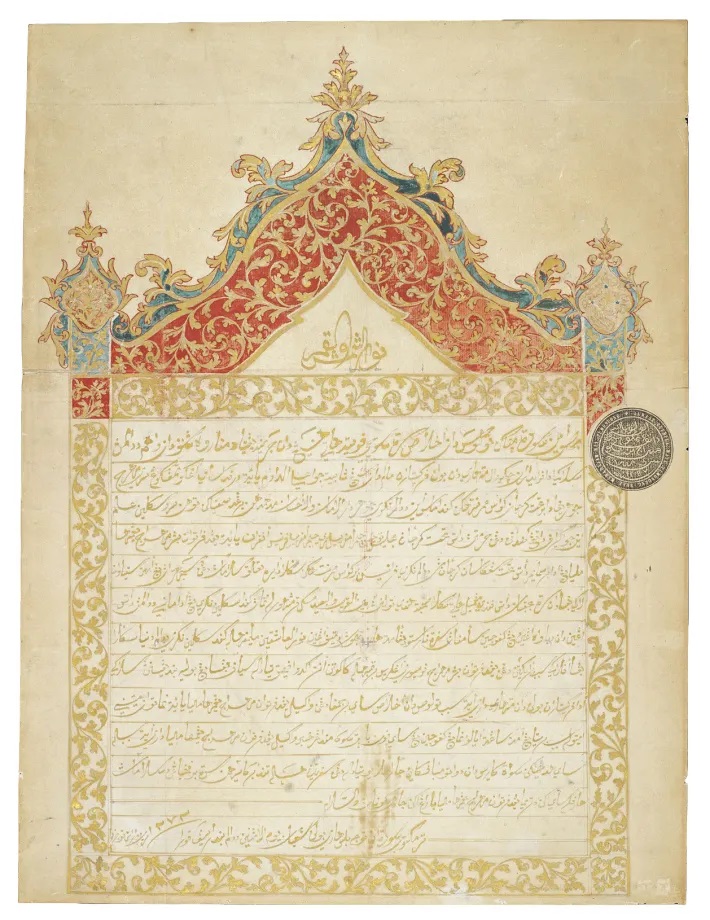

Another breathtaking but little-known document is an Ottoman land grant of 1628, bearing Sultan Murat IV’s great tughra: the stylised calligraphic rendering of the Ottoman emperor’s name that acted as his monogram or seal to authenticate royal documents. Here the sultan’s regnal name and titles are outlined in gold, with the constituent words acting as branches from which sprout red and blue flowers. The deed is written in Ottoman Turkish in gold and blue ink in ornate chancery script, in boat-shaped lines. Reflecting the great extent of the Ottoman empire at the time, the text attests to the transfer of land near Timișoara in present-day Romania.

From Johor, at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, comes the earliest known example of Malay chrysography – writing in gold ink – in a beautiful letter produced in 1857. It was sent by the ruler of Johor, Temenggung Daing Ibrahim, to Napoleon III of France. The epistle is more significant as a work of art than diplomacy: its 13 golden lines pay effusive compliments to the French emperor but adroitly offer little else of substance, for at this time Johor was firmly allied with the British.

There are two main methods of applying gold to the page, each of which produces different effects. The first uses gold leaf, which is gold beaten into a thin foil. This is applied to a surface, sometimes over a raised ground of gesso (plaster mixed with glue), then burnished until it gleams. The results are large areas of brilliant sheen. The other technique uses ‘shell’ gold, which is gold ground up into a fine powder. Its name derives from the traditional practice of storing it in seashells. This powder can be mixed with a binder to make a paint, allowing artists to apply the gold finely with a brush to create delicate paintings and calligraphy. This was also the method used to make gold ink, whether for writing lengthy texts or for highlighting certain words.

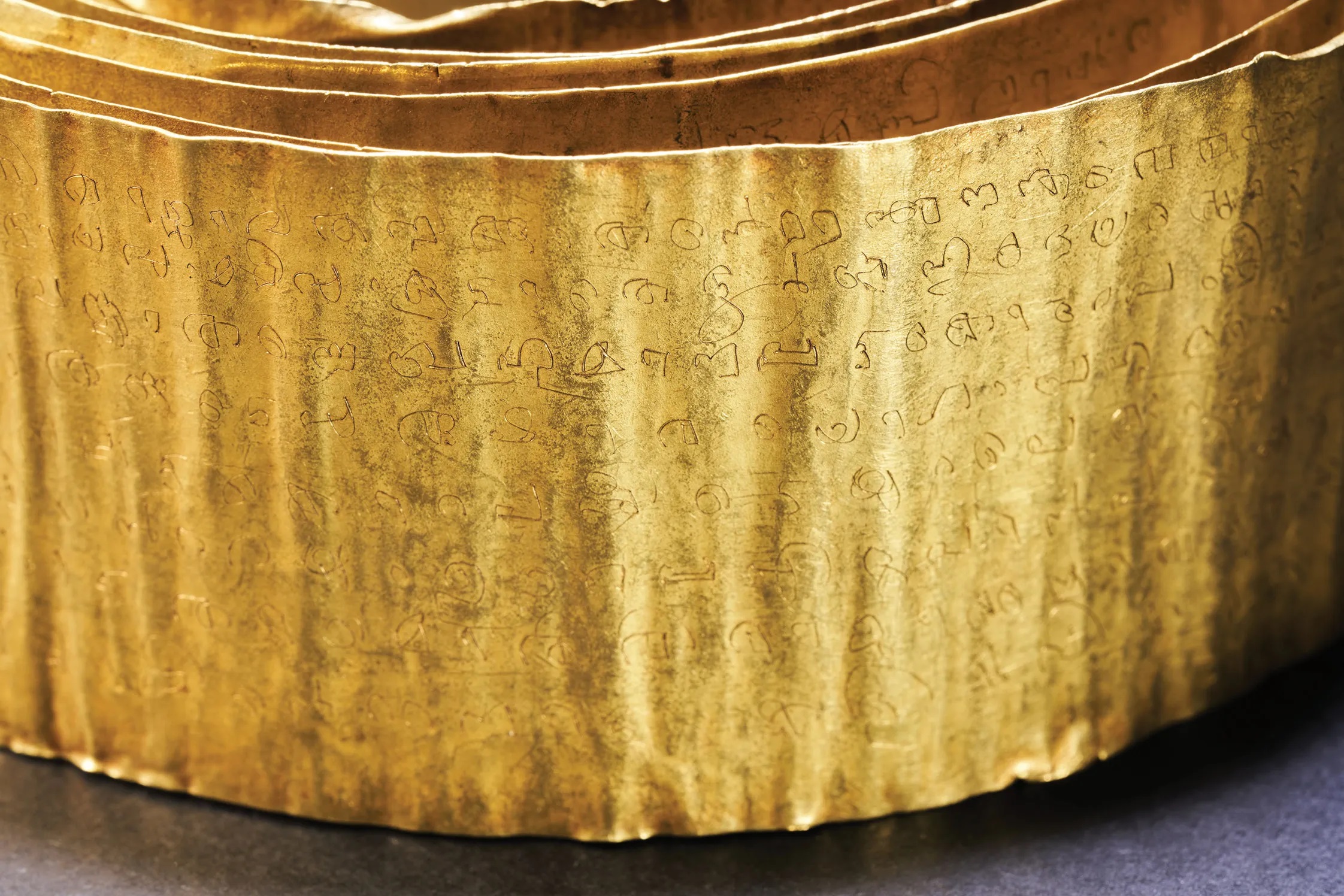

The magnificent books and documents exhibited illustrate myriad ways of writing and painting in gold. But perhaps the real stars of the show are the ultimate golden manuscripts, where the text is written – or, rather, incised – on an actual sheet of gold. The Gold exhibition has brought together in one dazzling case manuscripts of pure gold originating from South and South-east Asia, and spanning well over a thousand years. One cannot help but be struck by the similar shape of these manuscripts: all are written in horizontal format, on strips of gold that are longer than they are wide. Indeed, most books from South and South-east Asia written in scripts of Indian origin, on a range of materials such as birch bark, palm leaf, and locally made paper, are produced in horizontal or landscape format. This is in distinct contrast to European books and those from Arabic script traditions, which are generally in portrait format.

This is an extract of an article that appeared in Minerva 196. Read on in the magazine (click here to subscribe) or on our new website, The Past, which details of all the content of the magazine. At The Past you will be able to read each article in full as well as the content of our other magazines, Current Archaeology, Current World Archaeology, and Military History Matters.