Spiro: Renewing the World

Vast quantities of artefacts were found in a mound in Oklahoma in the 1930s. Together they tell an intriguing story of ritual and cosmic renewal. As an exhibition reuniting some of these objects travels to Texas, Lucia Marchini speaks to Michelle Rich and Eric Singleton to find out more.

The world was changing. Severe droughts that lasted decades at a time gripped the eastern part of North America. Large cities with their dozens of earthen mounds were struggling to harvest enough corn and other crops to feed their inhabitants. People of the Mississippian world called on their leaders to intervene.

At one site along the banks of the Arkansas River in eastern Oklahoma, people and objects convened in spectacular fashion to address this crisis. Riches from across North America – copper from the Great Lakes, shells from the Florida Keys and the Gulf of Mexico, and even obsidian from the area around present-day Mexico City – were brought together at Spiro around AD 1400, set up in a sacred tableau, and sealed inside a chamber within a mound, where they remained hidden for more than 500 years.

Spiro was not the biggest mound-site, having only 12 mounds and a population of several thousand. (The largest ceremonial centre was Cahokia in Illinois, with nearly 200 mounds and a population of 10,000 to 20,000 people.) Nor was it palisaded, and nor did its people depend on corn as their main crop, like other centres. But what really sets Spiro apart is this remarkable assemblage of items, the vestiges of a ritual enacted during the Little Ice Age seemingly to restart the world.

Many of the artefacts that shed light on Spiro’s unique role among these Indigenous communities were uncovered in a single context in the Craig Mound in the 1930s. For two years during the Great Depression, the Pocola Mining Company (PMC) dug up objects to sell. The number of high-quality objects that appeared from the now obviously important site led to the passing of Oklahoma’s first antiquities laws. Then, between 1936 and 1941, the University of Oklahoma collaborated with the Works Progress Administration, the University of Tulsa, the Oklahoma Historical Society, and the Woolaroc Museum to excavate what remained of the mound, revealing many more finds – altogether the largest set of artefacts known from any single Mississippian site.

Because of this chequered early excavation history, there is much that remains unknown about the original make-up of the assemblage, and the site is still the focus of ongoing research by the Spiro Landscape Archaeological Project, which returns to the field in May. The PMC did leave some notes and drawings, providing vital information about the arrangement of the objects, many of which are spread across collections today. Some of these artefacts have been brought together for an exhibition organised by the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum (NCWHM) in Oklahoma, in close consultation with the Caddo Nation and Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, the descendants of the Spiroan people. The exhibition opened at the NCWHM last year, before travelling to Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama, and now, for its final stop, the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA), Texas, where it recently opened as Spirit Lodge: Mississippian art from Spiro.

It is the first time that these objects – just a small fraction of what the mound once contained – have been reunited since they were removed from the ground. They tell the story of Spiro, but also of the beliefs and iconography of the wider Mississippian world, of which the site was evidently an important part. In the Midwest and the Southeast, Mississippian people developed a large and complex society between AD 800 and 1650. Their cities, or ceremonial centres, consisted of earthen mounds and plazas near rivers. These were cosmopolitan, well-connected places; people moved between towns and goods were traded over long distances, covering more than 1,000 miles.

People were also connected by a shared belief system with a tripartite universe. There is the above world, the supernatural realm of the Sun and Morning Star (also known as Red Horn, who in contemporary Pawnee traditions came to the earth as a meteor, bringing fire with him); the middle world, which we humans inhabit; and the below world, associated with chaos, underwater, and the night sky. All three were connected by an axis mundi or Tree of Life, via which supernatural characters and spiritual leaders could access different realms to make an impact on the real world.

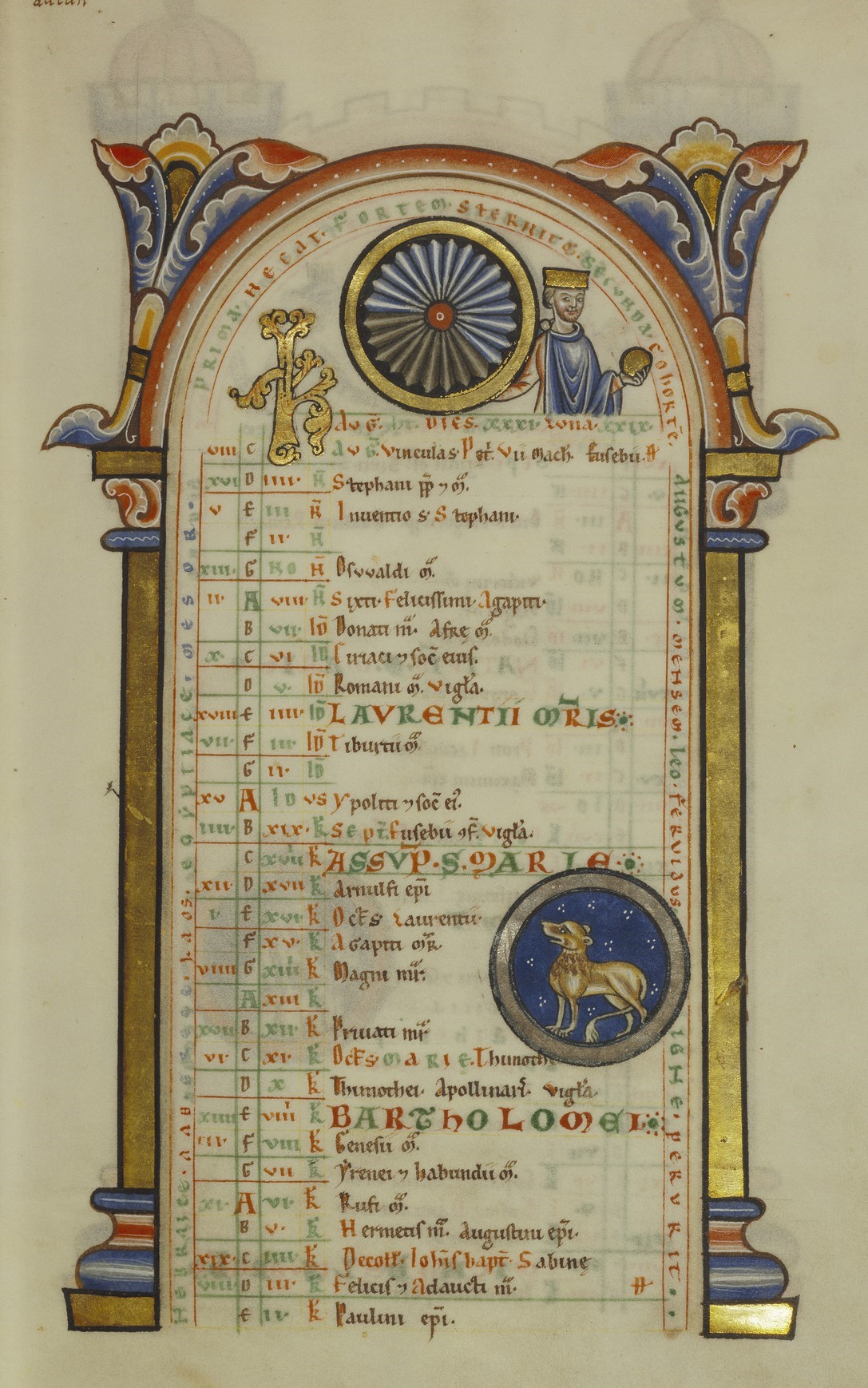

Spiro had been occupied since approximately AD 950. Important changes began after AD 1200, when the nearly 10m-tall mound that became the main part of the Craig Mound (originally four separate mounds that were later joined together with more earth) was built. Spiro’s inhabitants dug a pit into this mound. Known as the Great Mortuary, this was where they interred generations of their ancestors, along with objects brought from different settlements. Later, around 1350-1400, they dug into the mound and moved the burials to a different part of the Great Mortuary, making way for the building of a hollow chamber called the Spirit Lodge.

Here, the Spiroans placed objects of ritual significance filled with imagery relating to the cosmos in what has been described as a sacred tableau. Knowing how the world was created in their belief system and which characters were involved in the process, the Spiroans set out to do the same thing. These finds are the surviving remnants of what was probably a series of rituals to recreate creation and restart the world during the droughts of the Little Ice Age, which affected the eastern half of North America from around 1350 until around 1650.

‘What’s interesting is that recent archaeological research has uncovered across the site a series of post-hole remnants that indicate temporary housing’, says Michelle Rich, the DMA’s Ellen and Harry S. Parker III Assistant Curator of the Arts of the Americas and venue curator of the exhibition. ‘That supports this notion of a convening of people from across the Mississippian world at Spiro – local leaders, spiritual leaders, political leaders coming together and bringing all of their most powerful, potent ritual objects with them. I don’t want to trivialise it by making this comparison, but it’s like Burning Man, where thousands of people come together with their tents and their RVs, creating a town in the middle of the desert, and then they disperse again.’

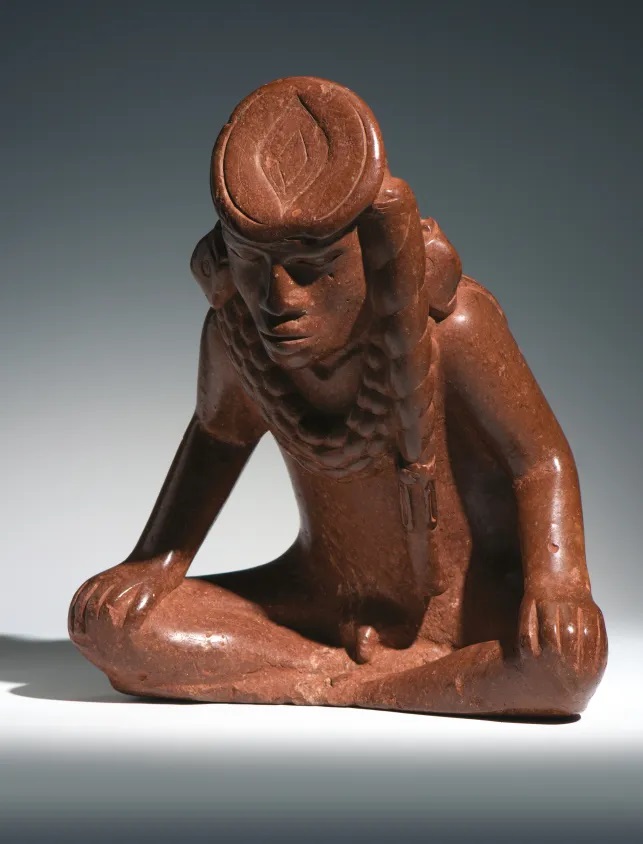

At the centre of the Spirit Lodge was a carved stone effigy pipe depicting Earthmother, the supreme provider and an essential ingredient for a new world. She holds corn and is responsible for rebirth. The placement of this life-giving figure in the centre of the floor has been interpreted as a means of establishing a new axis mundi between the tableau and the above and below worlds. Another fine effigy pipe – pressed into the wall of the hollow chamber – depicts Morning Star, seated and seemingly nude as befits a primordial god, but wearing a feathered cape, a beaded necklace, a palette with an ogee on his head, a horn hanging down from his hair, and other adornments, known as maskettes, in his ears. A carved wooden statue of First Man, a human who could perform rituals to interact with the spirit world, was here too, accompanied by two smaller ‘assistant’ statues. There were also 18 baskets filled with regalia, which enabled their wearers to embody a specific deity, bowls of pearls, arrowheads, earspools, and more.

This is an extract of an article that appeared in Minerva 195. Read on in the magazine (click here to subscribe) or on our new website, The Past, which details of all the content of the magazine. At The Past you will be able to read each article in full as well as the content of our other magazines, Current Archaeology, Current World Archaeology, and Military History Matters.