Luxor: Divine kings

After coronation, the new pharaoh would head to the temple at Luxor to assume the royal ka that flowed from the gods Horus and Re all the way down Egypt’s line of rulers. Nigel Fletcher-Jones takes us on a procession through this all-important site, developed by kings strengthening their claims to divine ka.

Five hundred kilometres south of Cairo, the neatly linear temple at Luxor stands in the long spiritual shadow cast by the vast complex at Karnak dedicated to the god Amun-Re – the ancient Egyptians’ supreme god and a fusion of Amun, the patron god here in ancient Waset (Luxor), and the creator god Re, whose cult centre was at Iunu (Heliopolis, outside modern Cairo).

Luxor temple is often visited as the sun sets on an exhausting day within its sprawling neighbour of Karnak. Yet, as weary visitors pass in the twilight through the iconic gateway or ‘pylon’ and along the central route, they are walking alongside many of the most famous figures in antiquity, including the Egyptian pharaohs Hatshepsut, Amenhotep III, Tutankhamun, Rameses II, and, much later, the Macedonian king Alexander the Great and, perhaps, the Roman emperor Diocletian. For this temple was dedicated to the divine Egyptian ruler or, more specifically, to the divine royal ka or ‘essence’ that flowed through the long line of Egypt’s kings.

While we now borrow the convenient concept of ruling dynasties (family or political groupings) from the 3rd-century BC priest Manetho, earlier Egyptians saw only a continuous line of kings that stretched back to the rule of the god Horus and, further, to Re, the creator sun-god. Thus, the royal ka connected the ruler directly to the gods and his divine predecessors, allowing the king to exercise supreme power as an intermediary between the celestial and earthbound worlds.

A new king’s royal ka had been with him since he was conceived, but his human form was only subsumed by the divine ka at his coronation. Henceforth, the king became semi-divine while on the throne and until his death, when he became fully divine. Most usually, after their coronation, the rulers of Egypt would come to Luxor each year in a great procession – known as the feast of Opet, which began at Karnak and ended at Luxor temple – to reaffirm the divine nature of the living king that he had inherited from his father. For this was always the Egyptian expectation: a king would die and would be succeeded by his son.

Over so many centuries, however, history could never quite force itself to be so neat. Dynastic families died out or the obvious heir might be female, a commoner, or even a foreigner. Succession to the throne might prove legitimacy in practice, but it also required a more miraculous intervention of the divine spirit. It was here at Luxor, for example, that the royal ka had descended on General Horemheb (reigned c.1323-1295 BC), a few years after the death of the childless Tutankhamun (r. c.1336-1327) that marked the end of the immediate family of the ‘heretic’ king Akhenaten (r. c.1352-1336). It was here, too, that Alexander the Great, already declared a son of Zeus-Amun by the oracle at the western oasis city of Siwa, rebuilt Amun’s shrine. It was even here that the Romans – during the reign of Diocletian (r. AD 284-305) – built a cult chapel celebrating the divine Roman emperor.

Surely, the significance of the site and its relationship to ruling Egypt was still clear one and a half millennia after the temple rose to prominence. For, although it is possible that there were cult structures here from the Middle Kingdom (1985-1650 BC), Luxor appears to have been first favoured by a great but anomalous figure: the female king Hatshepsut.

Hatshepsut was the daughter of the warrior king Thutmose I (r. c.1504-1492) and became the consort of his son and successor Thutmose II (r. c.1492-1479) – her half-brother. Following the unexpected death of Thutmose II, the throne passed to Thutmose III (r. c.1479-1425), his young son by a lesser wife. Under such circumstances, there was precedent for a dowager queen to take the role of regent, and the boy’s aunt, Hatshepsut, duly assumed this role. From the beginning, it was clear that Hatshepsut took up the role of regent in a pronounced manner, but it was not until the seventh year of Thutmose III’s reign that she had herself declared king and co-ruler (r. c.1473-1458). In justification, Hatshepsut’s propaganda asserted that her father had, in fact, chosen her as his heir and, indeed, that her mother had been impregnated by Amun-Re in the bodily form of Thutmose I and hence the royal ka had descended upon her.

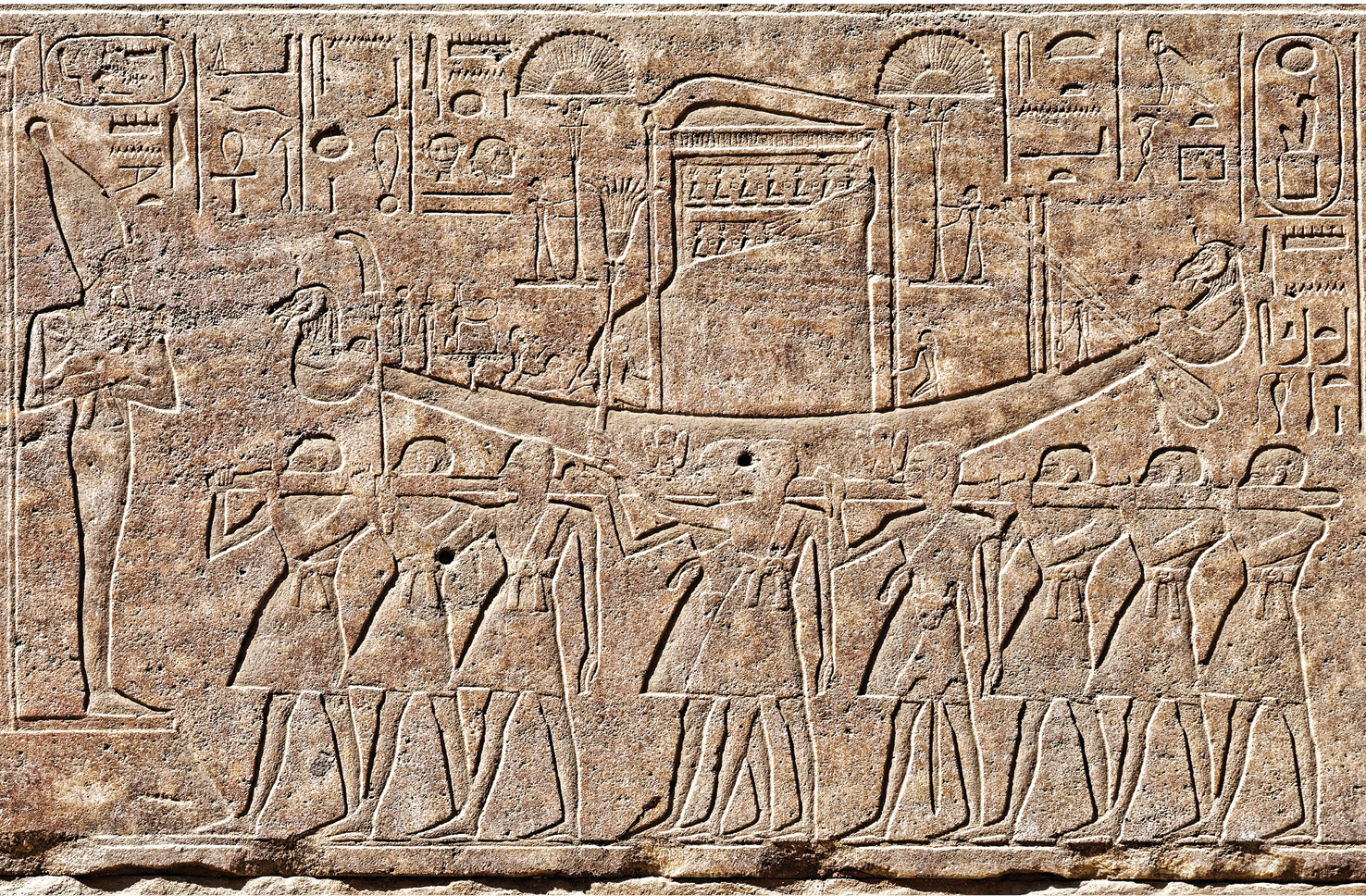

Throughout her reign, Hatshepsut never lost an opportunity to affirm her legitimacy as ruler through this narrative, and her extensive development of Luxor temple is to be seen in this light. Much of the work was later replaced, but we know that Hatshepsut built six stopping points for the boat shrines – sacred vessels containing the image of Amun, his consort the mother-goddess Mut, and their son Khonsu (together the ‘Theban Triad’) – that were carried from Karnak to Luxor.

This is an extract of an article that appeared in Minerva 193. Read on in the magazine (click here to subscribe) or on our new website, The Past, which details of all the content of the magazine. At The Past you will be able to read each article in full as well as the content of our other magazines, Current Archaeology, Current World Archaeology, and Military History Matters.

All images: Nigel Fletcher-Jones