Treasures of the Scythian Kings

Barry Cunliffe, among the most distinguished of world archaeologists, has recently drawn together the evidence for the Scythians in a comprehensive new book, The Scythians: nomad warriors of the steppe. Neil Faulkner asked him what we know of this most mysterious of ancient peoples.

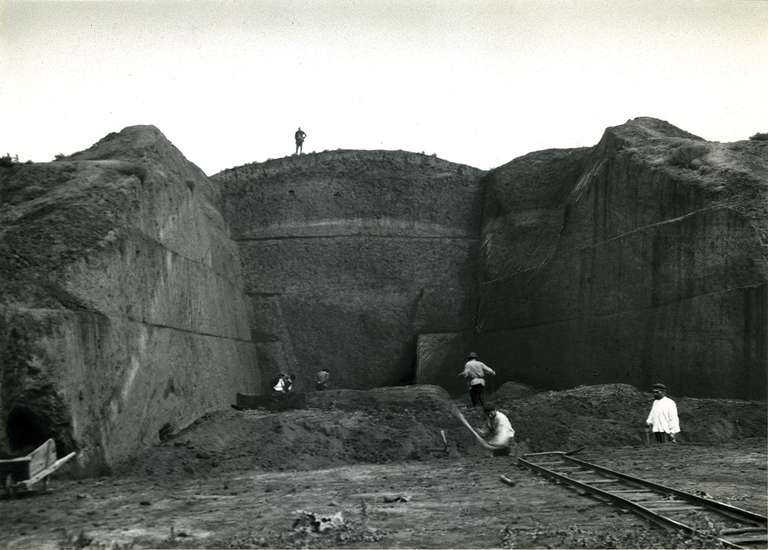

The 1913 excavation took the form of a giant trench cut into the side of an 18m-high mound. One of thousands of ‘kurgans’, that at Solokha in eastern Ukraine was among the largest, betokening the burial-place of Scythian nobility of the highest rank. As so often, the main chamber, centrally placed, had been plundered in antiquity. But there was a side chamber, and when Russian excavators reached it, the burial was found intact. A deep shaft descended to a long corridor leading to the burial chamber itself. The main interment had been placed in the largest of three recesses. The buried person, explains Barry Cunliffe, was wearing a Greek-manufactured gold torc around his neck and was surrounded by his personal equipment. On his right-hand side lay his ceremonial sword in a wooden scabbard covered with elaborate repoussé-decorated gold sheeting, with a second sword placed next to it. To the left, beyond the swords, was a small side-chamber created to contain a gold phiale (vessel) and a gorytos (quiver) sheathed in gold and silver decorated with battle scenes. Close to his right arm was a mace with a six-lobed head. Nearby were six silver vessels, a now famous battle-scene comb, a bronze helmet – Greek in origin, but modified to suit the wearer’s needs – and a pair of Greek bronze greaves with the tops cut off.

At the entrance to the chamber containing his body, a fourth set of equipment was laid out: a short-sleeved tunic covered with iron scales, two spears, a sword, and a number of arrows. Close by, along the north wall of the chamber, was the skeleton of another man, who appears to have been wearing scale armour. He may have been the armour-bearer of the warrior king. To complete the picture, to the south side of the royal burial was a small recess containing the funerary feasting equipment. There were three cauldrons with an iron flesh-hook and a bronze ladle. The burial assemblage also included a bronze basin, a rhyton (drinking horn) with silver rim, and ten Greek amphorae, once containing oil and wine. Not far away was the body of the cup-bearer.

It was last of the great kurgan excavations of the heroic age of Russian archaeology. Exploration had begun as early as 1763, after Catherine the Great’s armies had opened up the Pontic Steppe north of the Black Sea to archaeological investigation. Most of the mounds had been robbed, but some were found with treasures intact, and the Hermitage in St Petersburg acquired a growing collection of stunning objects from the burial chambers – objects of gold, of superb craftsmanship and artistry, many of them 2,500 or more years old. And as the armies of later Tsars extended the Russian Empire deep into Central Asia during the 19th century, other kurgans were investigated, some in the frozen wastes of Siberia, where tombs were uncovered with timbers in situ, textiles preserved, and bodies mummified – a rich gift of the bitter cold to archaeologists who found themselves uncovering the evidence for a civilisation that had previously been the stuff of legend.

The Greek myth of the Amazons – a race of barbarian warrior women – seems to have been based on the Scythians. Here, for example, is the anonymous Greek writer of a medical treatise (we know him as ‘Pseudo-Hippocrates’):

In Europe there is a Scythian race called Sauromatae… Their women ride on horseback, use the bow and throw the javelin from their horse, and fight with their enemies as long as they remain virgins; and they do not lay aside their virginity until they kill three of their enemies nor have any connection with men until they perform the sacrifice according to the law. Whoever takes to herself a husband, gives up riding on horseback unless she is obliged to by the necessity of a general expedition.

Certainly, when depicted in Greek art, the Amazons appear in unmistakably Scythian dress. Greek settlements lined the Black Sea coast and were in contact with the Scythian communities of the interior. Herodotus of Halicarnassus, the great historian and ethnographer of the 5th century BC, travelled extensively in the Pontic Steppe. But how reliable were his accounts, and those of others like Pseudo-Hippocrates? Were they accurate reporters, or mere collectors of tall tales from the outback? No one could be sure without archaeological verification. This we now have for many of the details supplied by the Greek writers, thanks to the exceptional preservation in the tombs, especially the frozen tombs at Pazyryk, where so much organic material has survived. Take the description by Pseudo-Hippocrates of Scythian ‘caravans’:

The Scythians… are called nomads because they have no houses but live in wagons. The smallest have four wheels; others have six wheels. They are covered over with felt and are constructed like houses, sometimes in two compartments and sometimes in three, which are proof against rain, snow, and wind. The wagons are drawn by two or by three yoke of hornless oxen… Now in these wagons live the women, while the men ride on horseback followed by their sheep, cattle, and horses. They remain in the same place just as long as there is sufficient fodder for their animals: when it gives out they move on.

In Kurgan 5 at Pazyryk, archaeologists uncovered the remains of a light carriage built of birch with four large spoked wheels. The four horses that had pulled it were buried with the carriage. The inner pair had been harnessed to a central pole, while the outer two had hauled on traces. This may have been a ceremonial vehicle – hence its deposition in a high-status tomb – but, in the light of this discovery, there can be no good reason to doubt Pseudo-Hippocrates’ description of Scythian caravans. The evidence of petroglyph images, clay models, and comparative anthropology suggest that a range of vehicles, open and covered, lightweight and heavy, were in use. Here was a nomadic culture with an exceptional repertoire of material-culture forms. Barbarians to the Greeks perhaps, but a people of ingenuity and skill in their adaptation to the harsh environment of the steppe.

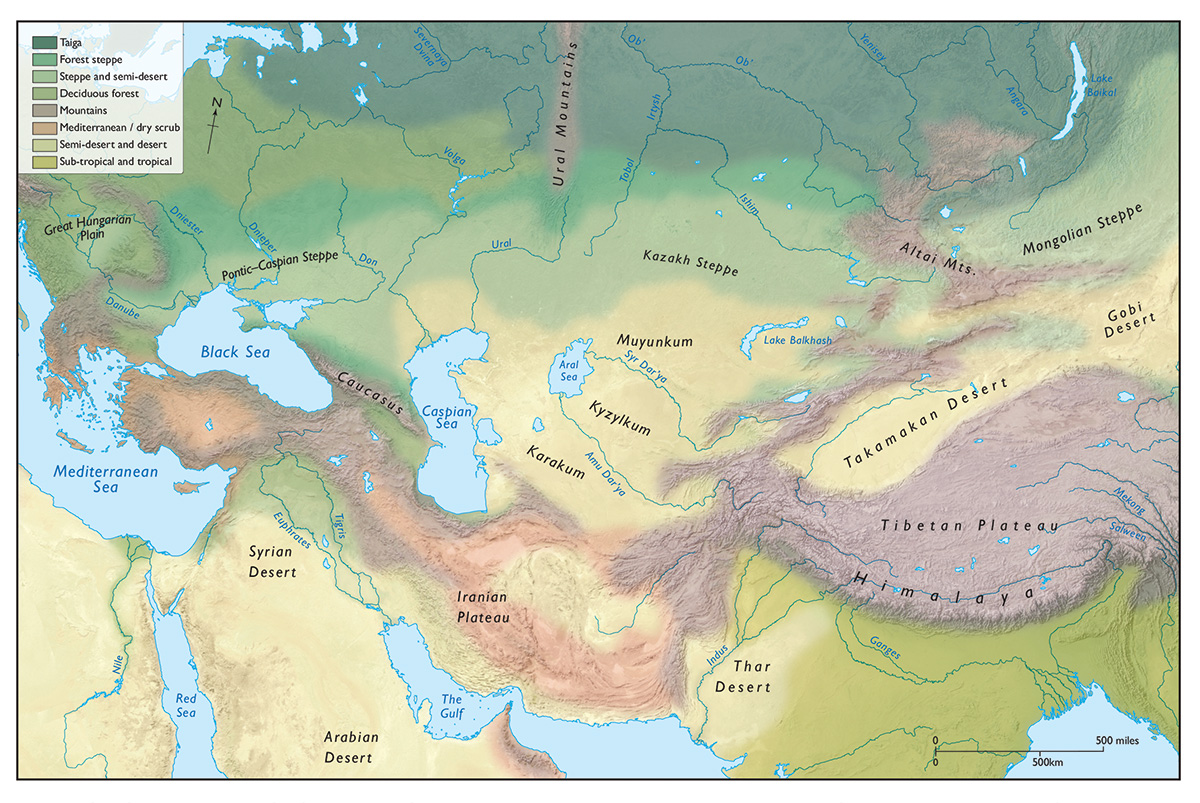

People of the Steppe

The Eurasian steppe is a belt of grassland several hundred miles wide which extends from the Pacific Ocean to the Hungarian Plain. To the north lie forests, to the south deserts, and the steppe has traditionally been home to nomadic herders of horses, cattle, and sheep. Six thousand miles in length east–west, it functions as a ‘corridor’ of movement, and the generally lusher grasslands towards the west (the ‘steppe gradient’) have tended to encourage movement from east to west in moments of ecological or social crisis. These, in the longue durée, have been relatively frequent, for modest fluctuations in climatic conditions can have a profound impact on the delicate balance between people, animals, and grazing on the steppe. It is an unstable equilibrium at the best of times, with the relative abundance of summer pasture contrasting with dependence on the reeds of rivers and marshes for animal feed during the bitter winters. A subtle shift in ecology can trigger successive shock-waves of folk movement across the steppe as whole communities trek west in search of fodder.

So the steppe peoples have always been warriors. They must be ever-prepared to fight for their place in the world – or, rather, for a new place further west where the grass grows taller. And these shock-waves have sometimes sent the steppe peoples barrelling beyond the steppe, colliding with more sedentary societies of cultivators to the south. Then they explode on to the historical stage, and we hear of them as Kimmerians, Sarmatians, Huns, and Mongols. All these are portmanteau terms to describe agglomerations of otherwise disparate tribes thrown together in moments of turmoil. Such were the Scythians, and for a long time we might have suspected this term to have been a crude lumping category created by Greeks, Persians, and other southerners to define a generic barbarian threat beyond their frontiers. But the archaeology implies a high degree of cultural affinity among the people of the Eurasian steppe for several hundred years during the 1st millennium BC. The Scythians, like other ‘barbarian’ peoples recognised by Greek writers – Celts, Persians, Libyans – turn out to have been an archaeologically distinct ‘culture group’.

Warmer and wetter conditions in the early 1st millennium seem to have expanded the grasslands and allowed a greater biomass of people and animals to subsist on the steppe. A growing surplus made it possible for an elite to elevate itself, becoming a class of princes, nobles, and warlords; and, no doubt, the tribal groups that did this most successfully, adapting themselves for more organised forms of warfare, would have gained advantage over their more ‘backward’ neighbours in times of stress. Thus, perhaps, overlaid on the recurring dynamic of ecological crisis and folk movement was a new dynamic of politico-military competition among rival elites.

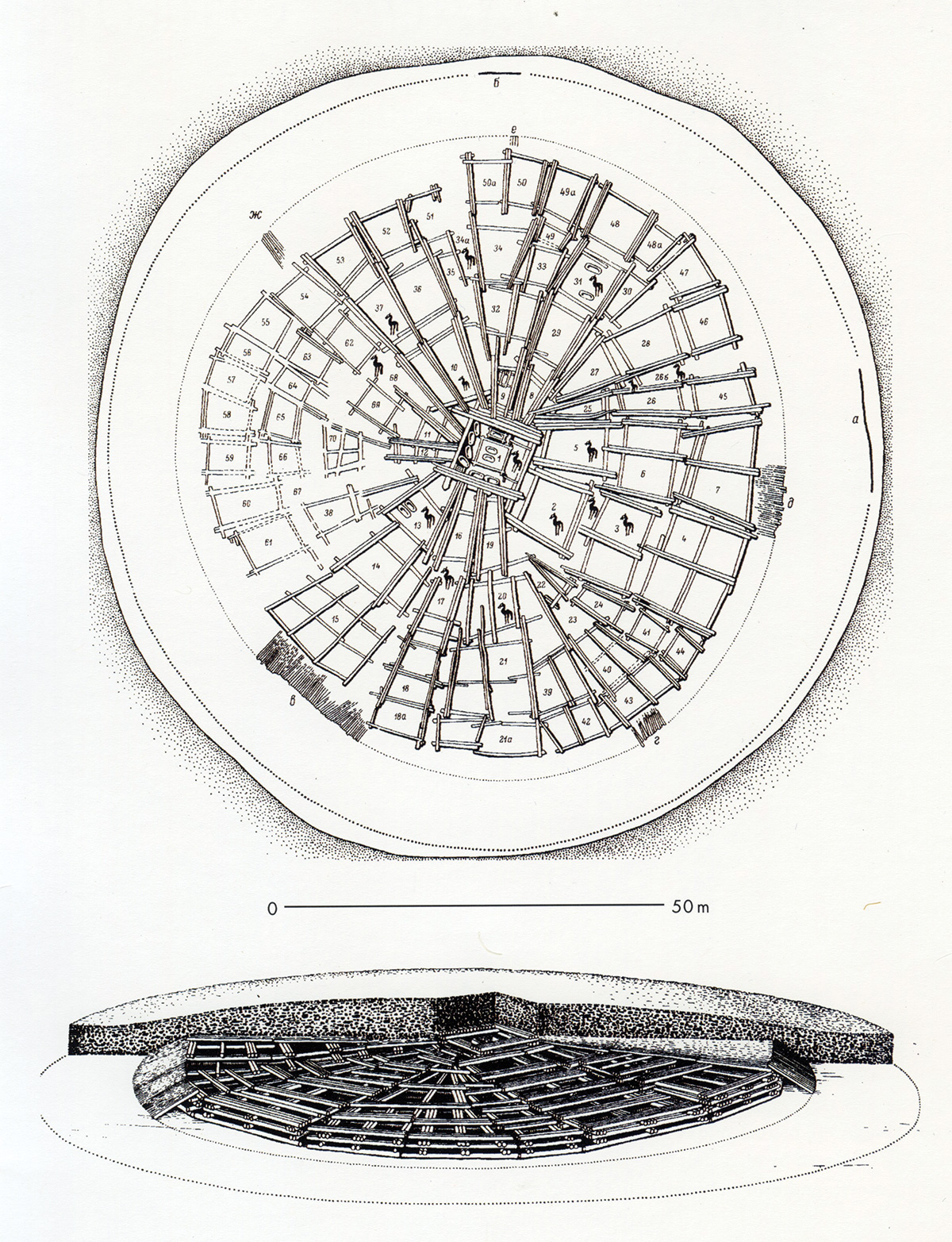

The Yenisei River Valley, and the Altai Mountains more generally, located on the western edge of Mongolia, may have been the primary incubator of these changes, for the distinctive features of Scythian culture seem to find their earliest expression in this region. The royal kurgan burial at Arzhan 1, for example, dating to the late 9th century BC, comprised a log-built grave chamber 8m across and a surrounding latticework of logs extending across much of the 110m extent of the mound. Some 6,000 tree-trunks were employed in the construction, and its accomplishment would have required up to 10,000 person-days of labour. The central chamber had contained an old man and a young woman, buried in finery of gold, turquoise, and coloured fabrics. Nearby were eight other bodies – presumably retainers, sacrificed to accompany the dead leader into the afterlife – and also six horses, their bridles decorated in gold. Among other grave offerings interred around the central chamber were some 150 horses with saddles and bridles.

Here, it seems, in the remote Altai Mountains, were the archaic Scythians, the primal lords of the grasslands, whose descendants would cascade across the Kazakh Steppe, through the Ural–Caspian gap, across the Pontic Steppe, and eventually through the Carpathian passes and out on to the Great Hungarian Plain, through several centuries of churning movement, cultural interaction, and violent collision.

The horse, of course, was central to Scythian life. A native of the steppe, the horse can survive winter on the snow-covered wastes, and it was domesticated early, perhaps even in the 5th millennium BC, and was likely reared partly for its meat, milk, blood, hide, and bone. As a mount, though, it was transformative. Horsemen can range 40 miles a day and thereby manage far larger flocks and herds. They can use horses to transport families, homes, and possessions long distances. And, of course, they can organise themselves into powerful armies. ‘The symbiotic relationship between horse and human’, argues Cunliffe, ‘was to become a decisive force in human history for the next seven millennia. It opened the way for two major advances: the use of teams of horses pulling chariots and the creation of bands of horsemen working in concert with devastating effects. These nomad hordes were soon to dominate life on the steppe and threaten the sedentary communities of Europe.’

It is Scythian warriors whom we primarily meet in the kurgan burials and represented on the sumptuous artworks contained within them. They wear pointed hats, long-sleeved tunics, and tight-fitting trousers. And, from the evidence of textiles preserved in the frozen tombs, we know that these were made of felt, fur, and soft leather, and that fabrics were often elaborately decorated with embroidered designs and gold and tin foil. The mummified corpses are sometimes covered in intricate tattoos, a complex interlacing of swirling animal motifs; the hope might have been that they provided magical protection against the blows of the enemy in battle.

Art and artefact combine to reveal the equipment of the nomadic steppe warrior. He carried the composite ‘recurved’ bow for long-range shooting; his quiver, often highly decorated, hung at his side. He was armed with a lance, either a close-range missile or a thrusting spear for use in the mêlée. He had a sword for hand-to-hand fighting. A helmet (homemade or perhaps a Greek import), body armour of metal scales sewn on to a leather jerkin, and a shield, perhaps of close-woven wicker, provided personal protection.

This material culture of the Scythians is as rich as any known in the ancient world; it equipped the people who used it for their life of mobility, animal husbandry, and war as efficiently as the technologies of the age were capable. What, though, of the spiritual life – even zeitgeist – of the Scythians?

There are clues about ritual practices in the reports of Greek ethnographers and the artefacts found in tombs; and perhaps evidence of belief systems in the extraordinary animal art that the Scythians carried with them from the edge of Mongolia deep into central Europe. Here, Cunliffe argues, at the Middle Danubian interface between Scythian and Celt, it appears to have influenced an emergent Hallstatt culture and the later La Tène culture that developed from it. This is astonishing: it means a cultural continuum that can be traced from Mongolia to Britain – a continuum across thousands of miles and several centuries – represented by dynamic forms of animal representation. But the evidence is compelling, for the similarities are striking and the links can be traced.

The Scythians ornamented their bodies, clothing, and metalwork with riots of curling, twisting, fighting beasts. We see recumbent deer, coiled felines, winged griffins, and birds of prey. We see predators tearing at sheep, deer, and horses; and sometimes predators fighting each other. We see human hunters in action, running down and spearing ferocious wild beasts, whether lifelike lions or mythic horned felines. And these images seem to blur into depictions of war, where human fights human, as if the battling beasts should be read as metaphors for battling people.

No doubt, Scythian animal art was ‘over-determined’, that is, embodied many layers of myth and meaning. Currents of archaic totemism are surely present, where tribal groups are symbolically represented by special animals. An element of hunting magic seems likely, where the hunter depicts his prey, and perhaps its destruction, and this representation of the wish is equated with its accomplishment. Are we not also witness to a whole conception of life as eternal struggle, a battle for survival, a brutal war of all against all raging across the steppe? And is this not also very much the art of a warrior aristocracy – the aggressively confronting heads, the savage fights to the death, symbolic of a world of competing warlord bands? Might this not help explain the phenomenal spread of this art form in Iron Age Eurasia, apparently jumping across otherwise formidable linguistic and ethnic barriers.

The Athenians employed Scythian slaves as policemen, and their most famous comic playwright, Aristophanes, satirised them on the 5th-century Attic stage as lumbering dimwits speaking pidgin Greek. The artists of the age – we have around 600 surviving representations on Attic black-figure pots – saw them as the quintessential barbarians in their beards, skin-tight trousers, and funny hats. It was ever thus: ‘we’ are civilised, ‘they’ are barbaric. The rich civilisation of the Scythians – a civilisation adapted to life and war on the Eurasian steppes – is now more visible to us than ever before, and Barry Cunliffe, a supreme master of archaeological synthesis, has done a superb job of collating and interpreting the evidence.

Further reading

Barry Cunliffe’s The Scythians: nomad warriors of the steppe is available from Oxford University Press, price £25.