Under the volcano - From Etna and Krakatoa to a tale of Gothic horror

Theresa Thompson investigates the history of a very hot subject, which can have cataclysmic results, at a new exhibition in Oxford

Seven years ago the eruption beneath the Eyjafjallajökull ice-cap in Iceland was a forceful reminder of the potency of volcanoes. The resulting plume of volcanic ash that was ejected many kilometres into the atmosphere caused huge hazards for air traffic across Europe, and in the days that followed its steam columns and fire fountains were witnessed by many in real time on news reports. Yet this was a relatively small volcanic eruption.

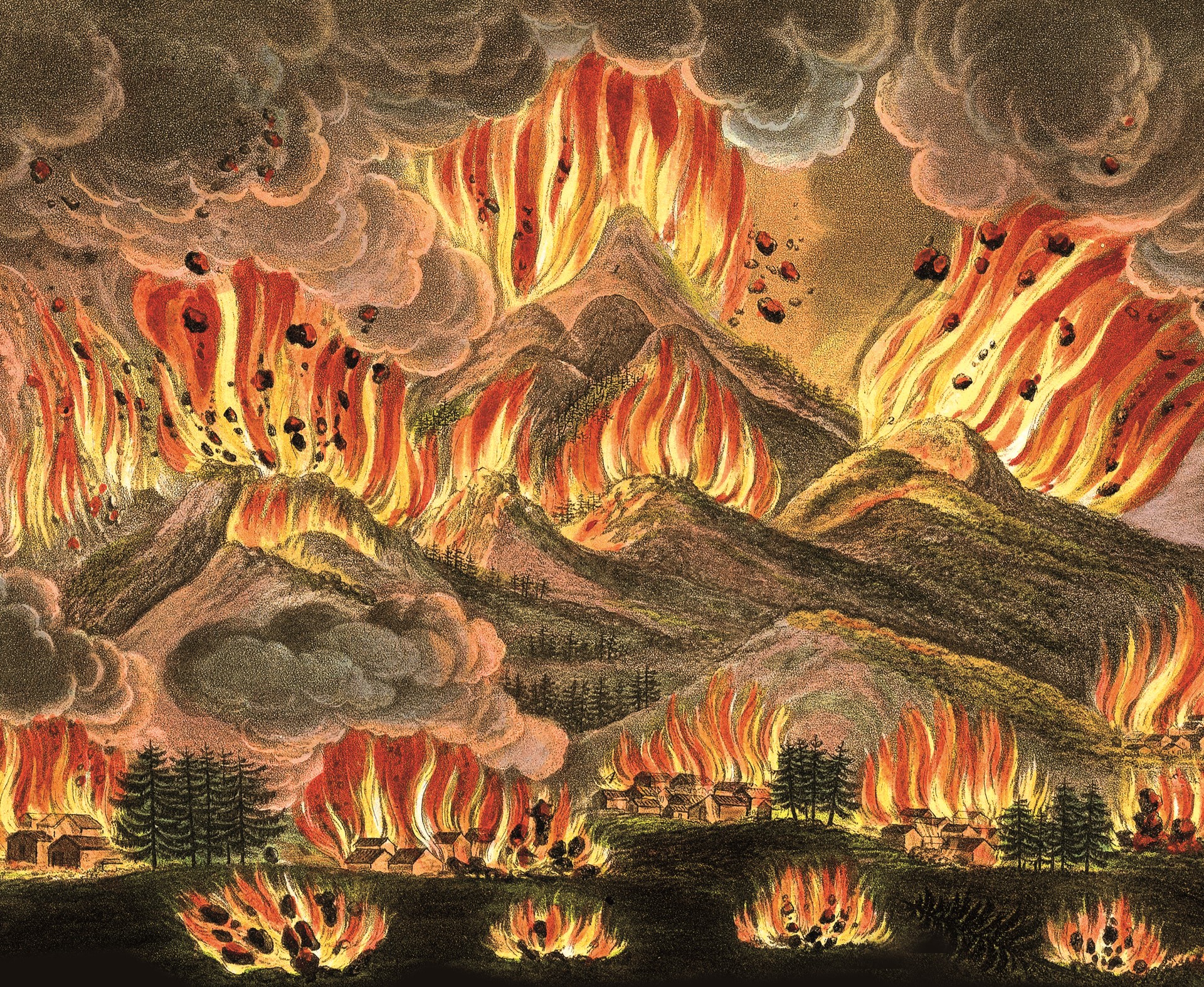

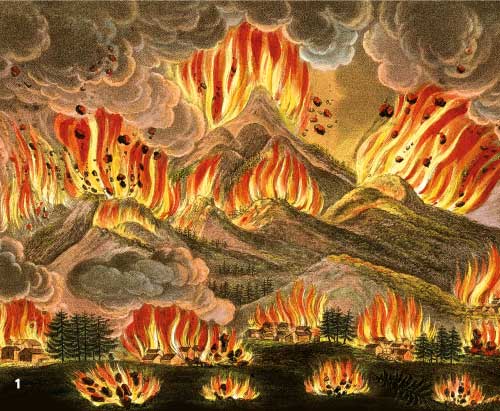

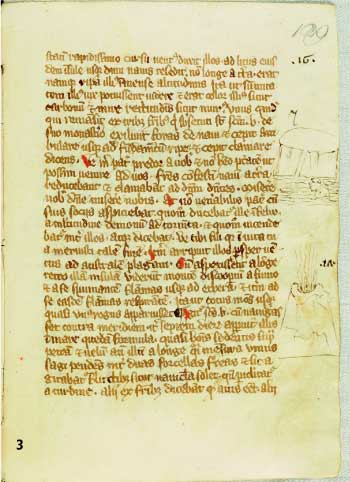

The huge eruption of Mount Asama in Japan in 1783 (1), recorded by Dutch doctor Isaac Titsingh, killed around 1500 people and lasted three months, while the eruption of the volcanic island of Krakatoa in Indonesia on 26 August 1883 was larger still, and one of the most violent eruptions of recent times. Not only did it cause an ear-splitting noise heard thousands of miles away and catastrophic tsunamis killing thousands of people, but it also triggered extraordinarily vivid sunsets around the world for months to come. So spectacular were they that the painter William Ascroft (1832–1914) recorded them in pastel on Chelsea Embankment in London that autumn. He published a series of paintings (2) that not only made his name, but also served as a detailed record of the meteorological effects of the eruption in the days before colour photography was in regular use.

A century earlier, in July 1783, the Worcestershire schoolteacher William Dunn (1731–95) noted in his weather diary that 'putrid air' had spewed across England following the eruption of Laki, a volcano in Iceland, on 8 June. He observed that the sun was 'red as blood with Thunder and Lightning' and a farmer was 'kill'd with his horse by lightning with a number of other beasts kill'd' during that hot summer.

Other writers who commented included the artist, writer and prolific diarist Reverend William Gilpin (1724–1804) who recorded his observations on the unusual weather that summer in the New Forest, Hampshire. He described how 'the sky was overspread with a dark dry fog', and how the heavy vapours hung around. Across Europe it was the same story, and many people suffered from breathing problems. Only later in the 1800s did scientists begin to understand the relationship between major volcanic eruptions and freak weather conditions that occurred miles away from the eruption site.

Throughout history volcanoes have captured the imagination. Eyewitness accounts like these, and others of fire-breathing mountains, blood-red streams of lava, burning rocks hurled by giants or gods, or myths about the underworld, have in their own way enhanced the gradual unfolding of the scientific understanding of volcanoes.

Handed down to us via letters, diaries, drawings and paintings, as well as early scientific observations and graphics, these first-hand accounts now form the basis of an exciting exhibition in Oxford. Volcanoes, which is currently on show in the new exhibition galleries in the Bodleian's Weston Library, is the brainchild of Richard Ovenden, Bodley's Librarian, and David Pyle, Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Oxford, the exhibition's curator.

'We are using archival material to gain more understanding of volcanoes,' explains Professor Pyle. 'You could say that we are filling in the gaps in our knowledge of the geology of volcanoes. We can work on volcanoes that are erupting, or on materials deposited as a result of eruptions many thousands of years ago and make inferences from these. But the period in between, when people have been making observations and capturing images in all sorts of ways, can lead to different insights.

Professor Pyle, a volcanologist whose doctoral research was carried out at Santorini, Greece, and who has studied volcanoes in Latin America, in the Caribbean and, most recently, along the Ethiopian Rift Valley, is interested in using historical sources to flesh out what is known about past volcanic activity and its societal impacts. He hopes this research will shed light on what might happen in the future in young or already active volcanoes.

Most of the material on display is from the Bodleian's own collection of printed treasures, dating mainly from the 16th to 19th centuries, some never previously publicly displayed. But among the 80 exhibits there are also loans from the Natural History Museum in London and from the University of Oxford's Museum of Natural History, the Museum of the History of Science, and Magdalen College in Oxford.

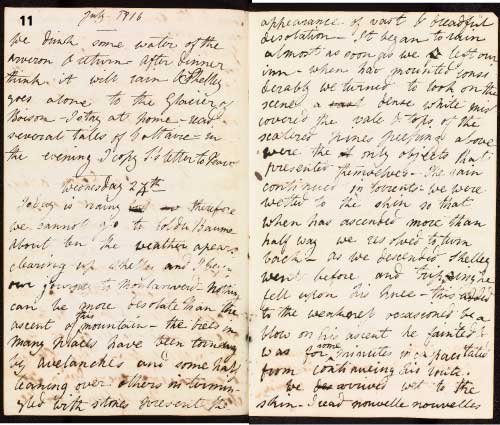

6. William Dunn's diary records 'putrid air' over England after the eruption of Laki in Iceland, July 1783.

Because the exhibition has been built around what is available in the Bodleian collection, it is not representative of volcanoes of the world. The exhibition does, however, look at some of the world's most spectacular volcanoes, including the famous eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, one of the most catastrophic in European history, and the best documented. Two of the first volcanic eruptions to be intensely studied by 'modern' scientists are the 19th-century eruptions of Krakatoa, whose effects in England were described by poets such as Gerrard Manley Hopkins and Alfred Lord Tennyon; and Santorini, where the huge caldera had been created by a massive eruption during the Minoan period, around 1650 BC.

In his book accompanying the exhibition, Pyle lists the more than 30 notable eruptions featured. They include Etna in Sicily in 1669, La Soufrière (The Sulfurer) on the Caribbean island of St Vincent in 1718 and 1812, and

20th-century eruptions such as Mount St Helens, USA, in 1980, Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991 and the recent eruption of Calbuco, Chile, which burst back to life in April 2015, giving less than two hours' warning after more than 40 years of silence.

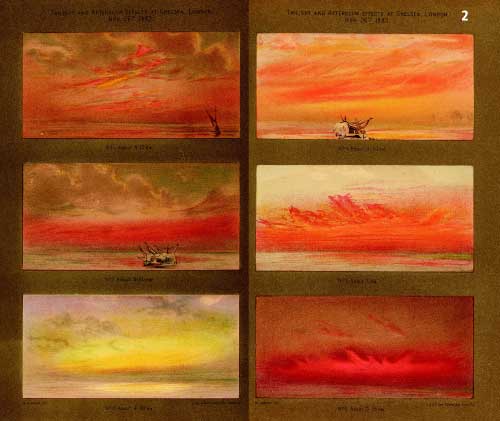

The earliest known image of a volcano was found sketched in the margin of a 14th-century manuscript (3) of the voyage of St Brendan, the Irish monk who travelled across the North Atlantic in the 6th century. In the epic tale of his voyage, he writes that he encountered wild seas, rare beasts and untamed islands, two of which, according to Pyle, were certainly volcanoes. The sketch he made is a pleasingly naïve representation of a volcano, but 'not too different to what most of us would draw today', says Pyle.

I wonder if the text gives us a clue to the volcanoes' whereabouts. But no, apparently they could be any one of a number of volcanic islands off Iceland or Greenland that have erupted and disappeared again. Instead, St Brendan colourfully describes 'great dark cliffs and smoking vents', 'mountains that vomited fire' and 'angry trolls that run down the mountain hurling rocks at the boat' – presumably volcanic bombs.

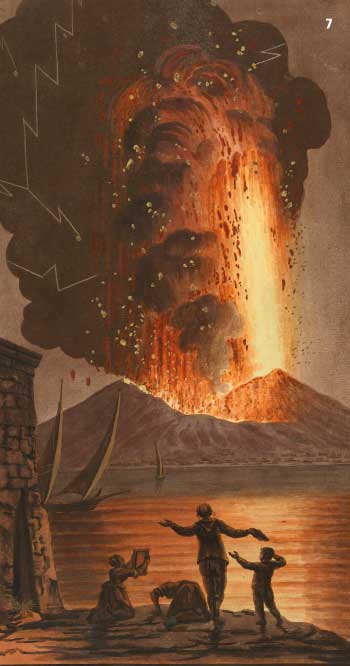

The human encounters with volcanoes that are explored in the exhibition range from the 17-year-old Pliny the Younger's account of the dramatic eruption of Vesuvius two millennia ago, to early Renaissance explorers (mostly European) who reported strange sightings of mountains that spewed out fire and stones, to the fascination of Scottish diplomat Sir William Hamilton (1730–1803) with Vesuvius while he was ambassador to the court of Naples in the last four decades of the 18th century. His residence at the foot of Vesuvius put him in a prime position for witnessing the changes in the volcano and the climate around the mountain. Vesuvius was active at the time, with frequent eruptions of lava and 'fire fountaining' episodes. The spectacle attracted sightseers, and Hamilton, who hired a monk to make daily observations, climbed the mountain on many occasions and even stayed on it overnight to witness the 1766 eruption. He later described this event in a report to the Royal Society. Hamilton was in the right place at the right time. As a result, he became 'one of the first descriptive volcanologists', according to Pyle.

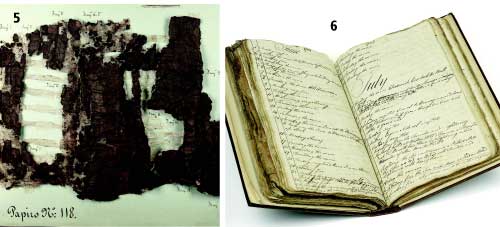

Hamilton's descriptions were published later that year in Campi Phlegraei: observations on the volcanoes of the two Sicilies, a scientific treatise beautifully illustrated with hand-coloured plates (7) by the artist Pietro Fabris (1740–92) that is one of the treasures in the show. Another highlight from Vesuvius is the fragments of burnt (carbonised) papyrus scrolls (5) from the library of a private house in the Roman town of Herculaneum, which were buried during the AD 79 eruption.

'It's interesting to see how much people knew about volcanoes in previous centuries,' says Pyle. citing material particularly from the 17th century. 'Of course, a lot of this was recycled from the early scholars and Classical mythology. The volcanoes of Classical Italy – Etna, Vesuvius, Stromboli and Vulcano, the Aeolian island that gave us the name – were all well known to the ancients.'

By the 6th century BC, Heraclitus, Pythagoras and Anaxagoras had all helped to develop ideas of a central fire within the Earth that caused winds, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The Greek philosopher Empedocles, living in Sicily, supposed that the interior of the Earth was molten. According to legend, he died by flinging himself into Mount Etna's crater in an attempt to prove his immortality: 'Great Empedocles, that ardent soul, leapt into Etna, and was roasted whole.'

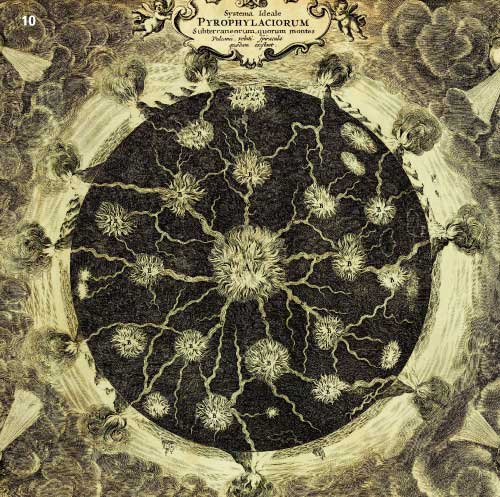

The accomplished 17th-century German scholar, Athanasius Kircher, wrote some spectacularly illustrated and encyclopaedic accounts of the workings of nature. Although he was using the Classical elements of earth, fire, air and water, he had, Pyle tells me, a scholarly view of the world as a whole organism, and drew analogies with the interior of the human body. He was also one of the first to create a map showing the locations of all the known volcanoes of the time, and the first to propose that they had subterranean origins. Kircher's stunning illustration of the Earth's 'subterranean fires' (9) shows the 'fires' escaping at the surface of a volcano, while a cutaway of Mount Etna (10) shows the fires and fissures inside the caldera.

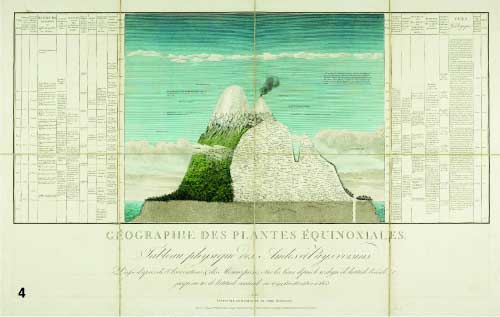

The early 18th and 19th centuries saw a huge growth in the natural sciences. Reports of expeditions made by natural historians, Alexander von Humboldt, Charles Daubeny and Charles Darwin, added to the growing body of knowledge on volcanoes. Although Darwin's voyage on HMS Beagle (1831–36) took him to many volcanic islands, it was the great earthquake he encountered in Chile that started him thinking about the links between mountains, earthquakes and volcanoes. The great Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt climbed many of the highest volcanoes in the world. In June 1802, he attempted to climb Chimborazo, a volcano in Ecuador (over 19,000ft) and made many observations on the way up. Two of his infographics about Chimborazo (4) can be seen in a section of the exhibition that examines the emergence of the science of vulcanology. One cross-section details the physical and biological structure of the giant volcanic massif. 'It is astonishing to think it is now over 200 years old,' Pyle observes. 'If it was today, a scientist would still try to represent it in a similar way.'

All images © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

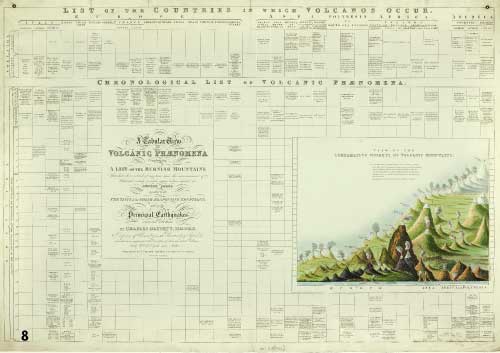

Likewise, the work of Charles Daubeny, a botanist, geologist and professor of chemistry at Oxford University in the early 1800s, contributed greatly to this emerging field of science. In 1826, he wrote the first systematic discourse on volcanoes (8), which was one of the volumes that Darwin took with him on HMS Beagle. Daubeny's pictorial summary of the world's volcanoes, showing comparative heights and their history, is on show in Oxford. There are also examples of early 19th-century brass scientific instruments, such as a mountain barometer and pyrometer, which naturalists took with them.

William Dunn's 1783 weather diary (6) is part of a display that examines the long-distance effects of volcanic eruptions. In April 1815 came the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia, said to be one of the greatest causes of atmospheric pollution in 19th-century Europe. A letter from Java that appeared in The Times newspaper in November 1815 described the 'most tremendous eruptions of the mountain Tomboro that ever perhaps took place in any part of the world'. It was not until the summer of the following year, 'the year without summer' that the wider effects of the eruption began to be felt around the globe. These included crop failures and famine across parts of Europe, Asia and the eastern United States. In that sunless summer of 1816 Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron took a holiday on the shores of Lake Geneva in Switzerland. The volcanic eruption made the weather so dire that they stayed indoors, entertaining themselves by making up ghost stories. The 18-year-old Mary's imagination, perhaps ignited by lightning flashing over the lake, conjured up the idea for her novel, Frankenstein. Her journal (11) open at pages in July where she writes of the persistent rain is on show. This is just one more eye-witness account to fill in scientific gaps. 'Looking back at history can help us learn valuable lessons about how best to reduce the effects of future volcanic disasters,' says Pyle. 'Humans have lived with volcanoes for millions of years, yet scientists are still grappling with questions about how they work.'

The enormous range of accounts in this exhibition bears witness to the power that volcanoes have over our imaginations. Captivating and dramatic, potent and beautiful, terrifying and deadly, they have long been used as metaphors for civilisation's fragility, making Volcanoes a compelling exhibition.