Tantra: From Ecstasy to Enlightenment

Lindsay Fulcher enters the transgressive realm of Tantra. This rebellious Indian cult, which has overturned religious, social, sexual, and political norms from AD 500 to the present day, is currently being celebrated in an exhibition curated by Imma Ramos at the British Museum.

With the publication of Beyond the Pleasure Principle in 1920, psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud concluded that all our instincts fall into one of two major categories: Eros (life instincts, including sexual instincts) or Thanatos (death instincts). Sex and Death are undoubtedly two potent forces that drive humankind, but what if the power of these energies could be harnessed and used to produce enlightenment? This is one of the central questions, but by no means the only one, explored in Tantra: enlightenment to revolution, a major exhibition of more than 100 objects, curated by Imma Ramos and currently on show at the British Museum.

Prior to this, the first exhibition of its kind to be held in the West – named simply Tantra – was curated by Philip Rawson (1924-1995) at the Hayward Gallery in 1971. At the time, Rawson was Keeper of the Oriental Museum (then known as the Gulbenkian Museum of Oriental Art and Archaeology) at the University of Durham, where there were galleries devoted to both Tantric and Daoist art. He was also a lecturer on the undergraduate Indian Civilisation course and the author of many books on art, including two definitive volumes on Tantra. In one of them, Tantra: The Indian Cult of Ecstasy (published by Thames & Hudson, 1973), he writes beguilingly:

Tantra has no dealing with fantasy. What it describes and maps is a world of realities, a world which may only be visited by following the maps. It is there to be found; but someone who has not visited it can have no idea what it is like. For there is no way of examining it from the outside. It is what we are – although we don’t usually realise the fact – and we can never step out of it to take an analytical view.

Despite Rawson’s impeccable academic and artistic credentials, the fact that he went on to describe Tantra as ‘a vision of cosmic sexuality’ and stated ‘it asserts that, instead of suppressing pleasure, vision and ecstasy, they should be cultivated and used’ meant that many people who saw this 1971 exhibition took Tantra to be an add-on to the demands of the 1960s counterculture for ‘free love’. Even today, any mention of it tends conjure up tabloid rumours of the singer Sting’s alleged sexual prowess gained through following Tantric practices. But, although there is a small section on the appropriation of Tantra by pop stars in the latest British Museum show, its curator Imma Ramos is keen to present us with a much deeper exploration – more cosmic than carnal – and one that tracks Tantra’s effect on historical events, from AD 500 to the end of British colonial power in India in the 20th century, and on into 1960s pop culture and feminism up until today.

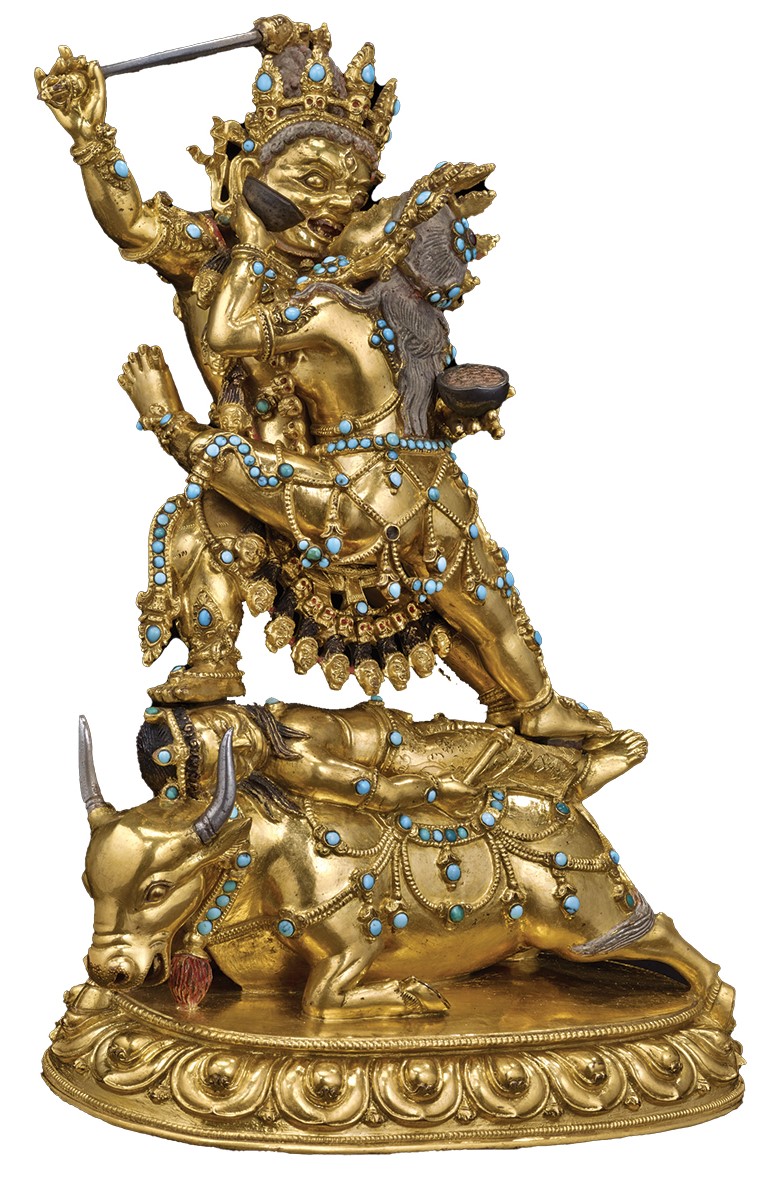

Size: 21.8 x 15.8 x 11.4cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum

This is not to say that the sexual side of Tantra is underplayed in the new exhibition; on the contrary, the galleries are alive with images of entwined gods and goddesses enjoying ecstatic union. The first image that greets us is one showing yab-yum (‘father-mother’ in Tibetan) – two divine figures locked in a serpentine embrace. These lovers are embodiments of the goddess of wisdom (prajna) and the god of compassion (karuna), who together can lift the Tantric practitioner, or Tantrika, above the endless cycle of rebirth.

Another example of yab-yum can be seen in the 16th- to 17th-century Tibetan gilded bronze sculpture of the meditational deities, Raktayamari and Vajravetali, locked erotically together while trampling on Yama (the Hindu god of death) and his buffalo vahana (vehicle).

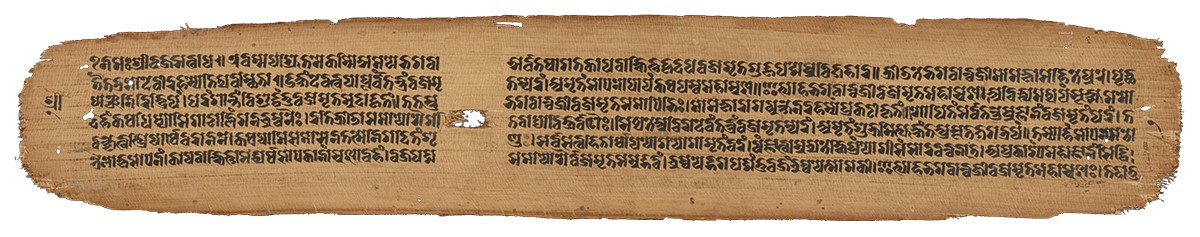

The philosophy of Tantra is rooted in sacred texts named tantras (derived from the verb tan, meaning ‘to weave’ or ‘to compose’). These texts, both Buddhist and Hindu, are often composed in the form of conversations between the god and the goddess. In the Buddhist Vajramrita Tantra (Nectar of the Thunderbolt Tantra), written in AD 1162, the goddess Mamaki asks the Buddha how to get access to the nectar (amrita) of the thunderbolt (vajra), which will give her power and immortality. As Ramos explains:

The Buddha tells the goddess it can accessed through pleasure, including sexual union, if both partners have internalised the deities… The text instructs the reader to keep its teachings secret, revealing them only to an initiate who ‘desires the supreme awakening’.

While the 14th- to 15th-century Hindu tantra Yoginihridaya (Heart of the Yogini), which consists of a dialogue between the goddess Tripurasundari and the god Bhairava, gives ritual instructions for divination. Other benefits of Tantric ritual include longevity, prosperity, political gain, defence against malevolent forces, the conquering of obstacles, and even invisibility and the power of flight.

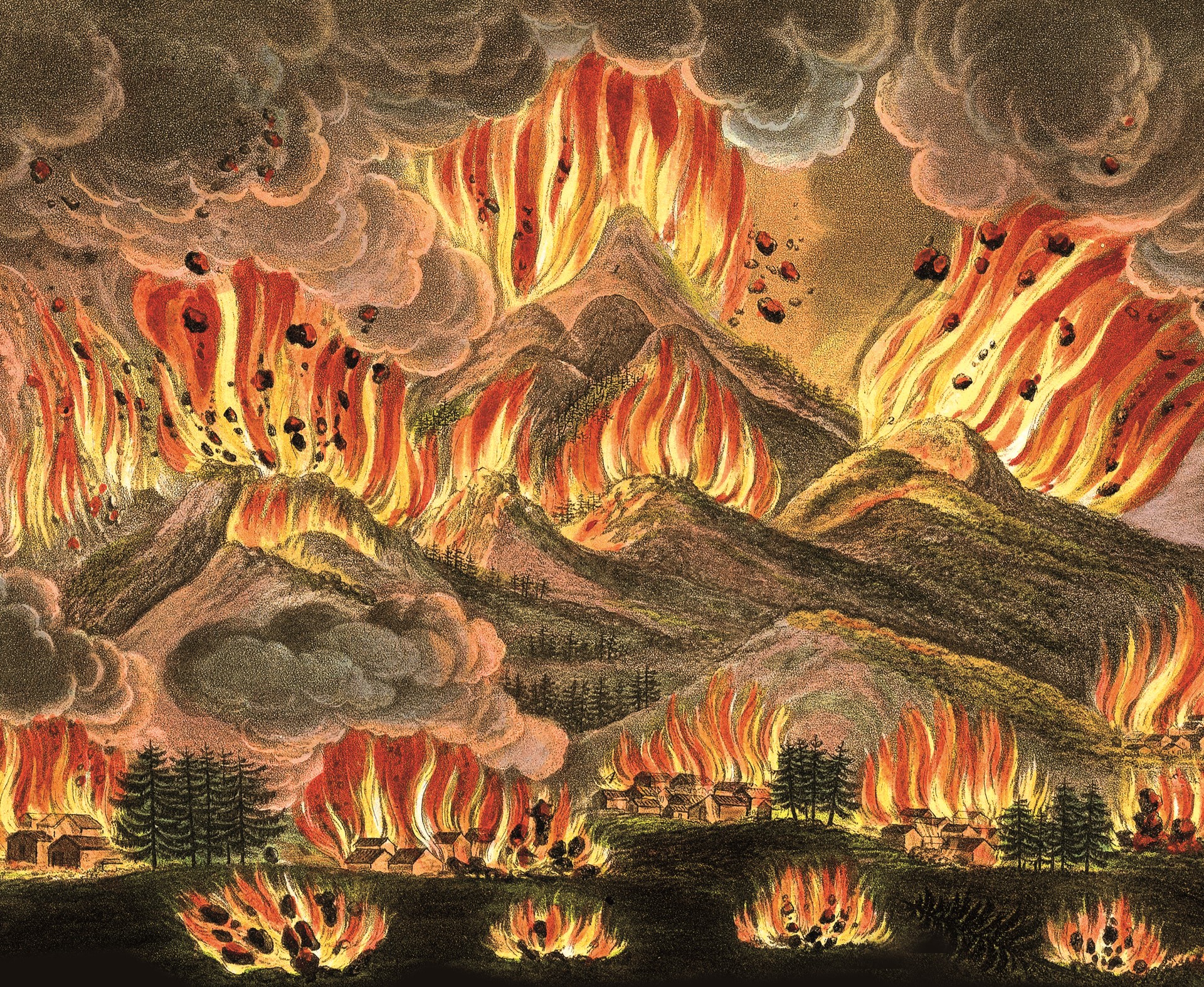

These tantras describe in great detail the procedures which the Tantrika should follow. Mantras, power words in which each syllable embodies the nature of a deity, are chanted while, at the same time, the disciple visualises the essence of each sound. To help in this task, he or she also uses yantras or cosmic diagrams. By all these means, the disciple hopes to merge with the cosmic form of the goddess. Tantras also describe transgressive acts to be performed in rituals involving taboo activities, such as exuberant sexual activity, excessive imbibing of intoxicants, the devouring of meat, and the smearing of the body with cremated human ashes – all of which are undertaken to invoke all-powerful Tantric deities. Through visualisation, the participants in the rite identify with the god or goddess and are lifted up into a divine state of ecstatic bliss.

The earlier 8th- to 9th-century Hevajra Tantra states: ‘By passion the world is bound; by passion, too, it is released’. Some ten centuries later, in his Proverbs of Hell (1790-1793), William Blake reworded this dictum: ‘The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.’ Whether Tantric excesses should actually be enacted depends, of course, on whether the cult follower decides to take the vamachara, the left-hand path, or instead sees these transgressive rites as purely symbolic and sticks to the safer right-hand path, known as dakshinachara.

Although Tantra cuts a swathe across Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, it is not, in itself, a religion. It may best be described as a philosophy or even a way of life, a cult of action. Its texts, which date from the 6th to the 19th century AD, tell you in detail how to enact rituals which may involve hatha yoga, the recitation of mantras, visualisation using yantras, meditation, or making offerings to the deity being invoked, as well as practising the sexual act itself.

Tantra is essentially rooted in the idea that all material reality is animated by Shakti, unlimited divine feminine power, which can manifest as benign and nurturing, or terrifying and destructive. This goddess-worship is yet another way in which Tantra challenged the status quo of Indian patriarchal society and religion. Gender is, as it were, turned on its head. As Ramos explains in her book that accompanies the exhibition:

Power is central to Tantra – a power described and visualised as feminine, resulting in the centrality of goddesses within the movement and inspiring the dramatic rise of goddess worship (Shaktism) in medieval India. The goddesses venerated by Tantrikas directly confronted traditional models of womanhood as passive and docile in their intertwining of violent and erotic power. According to many Tantric texts, the veneration of goddesses should carry over into the veneration of mortal women as natural embodiments and transmitters of Shakti. This marked a dramatic departure from previous orthodox Hindu and Buddhist teachings regarding the status of women.

In Tantra: enlightenment to revolution, the Great Goddess, who stands at the centre of this teaching, is shown in all her various manifestations illustrating her all-enveloping irresistible power. A 9th-century sandstone temple relief, from Madya Pradesh, shows the ferocious goddess Chamunda dancing on a corpse, while in later galleries 19th-century images show Kali (which means ‘black’), the all-devouring female deity of Time, striding over Shiva, and also as a symbol of an independent rebellious Mother India rising up against British colonial rule. According to Ramos,

The Tantric worldview sees everything as animated by Shakti – unlimited, divine feminine power. The earliest known text to describe the idea of Shakti is the Devi Mahatnya (Glory of the Goddess), dated from c.AD 400-600. It identifies Shakti with Devi or Durga, the Supreme Goddess, from whom all other goddesses emerge… Durga is a weapon-wielding, lion-riding warrior who must fight a series of demons that threaten the stability of the universe. Famously she slays the buffalo demon, Mahisha (an embodiment of ignorance), whom the gods had been unable to defeat.

Durga is often assisted by other wild, bloodthirsty goddesses known collectively as the Matrikas, or the Mothers. The Seven Mothers (Sapta-Matrikas) are depicted with Shiva on a 10th-century sandstone temple panel also from Madya Pradesh. But among these Matrikas, three of them – Maheshvari, Vaishnavi, and Indrani – had a maternal side and are shown elsewhere holding children on their laps. This contradictory mix of benevolence and violence, beauty and horror is embodied in the Great Goddess and runs right through Tantra.

Krishnanagar, Bengal, 1890s. Painted and gilded clay. Size: 53 x 29 x 43cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum

By the 7th and 8th centuries, the Matrikas had evolved into the seductive yet deadly Yoginis, the witch-like goddesses of Tantric Hinduism. We meet these medieval ‘shapeshifters of the sky’ early on in the exhibition – they can appear as women, birds, snakes, tigers, or jackals, but we get to see them as screeching, bird-like entities flying across the twilit sky in an animation with a chilling soundtrack. In order to gain their magical powers, Tantrikas appeased them in nocturnal cremation grounds with ritual offerings of blood, alcohol, and sexual fluids. But this was a highly risky undertaking for, if a mistake were made, the Tantrika could be crushed and consumed in an instant, as described in a 7th- to 8th-century text, the Brahmayamala:

The [practitioner] of great spirit should recite the mantra, naked, facing south. After seven nights, the Yoginis come – highly dangerous, with terrifying forms, impure, angry and lethal. By seeing this, the [practitioner] of heroic spirit should not fear, after prostrating, he should give them the guest-offering. [They become] pleased towards the practitioner with [heroic] spirit… And touching him, they tell truly [the future], the good and bad. If by mistake a practitioner of weak spirit should tremble, the Yoginis… devour him that very moment.

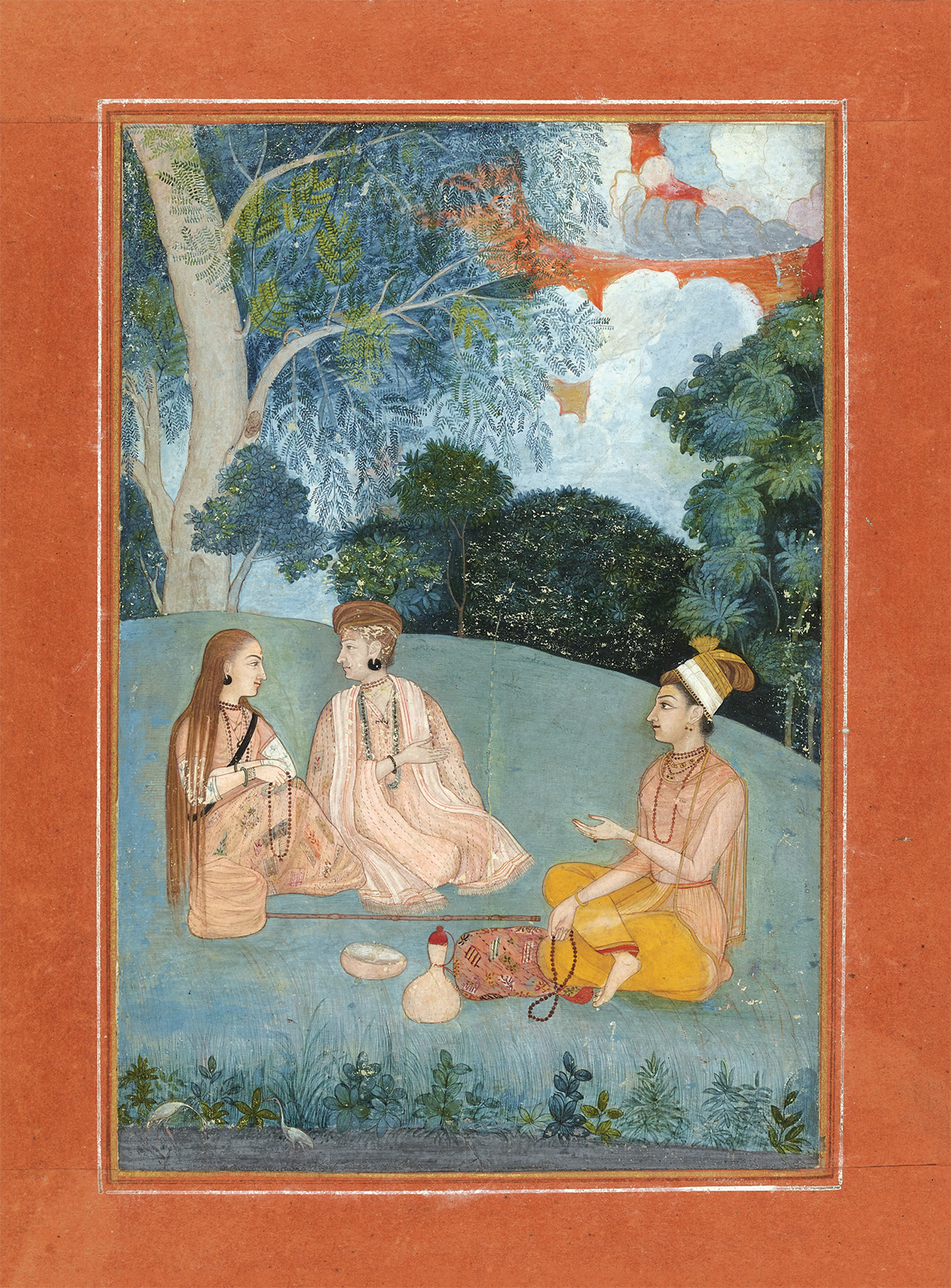

Later in the exhibition, a gentler side of Tantra is portrayed in an 18th-century court painting showing a woman visiting two calm, fully clothed, seated female gurus, or yoginis, of the Tantric Nath order. The Naths, who developed Tantric methods for raising kundalini (female energy) using hatha yoga practices, were believed to live for hundreds of years and were regarded as the guardians of esoteric alchemical knowledge. They became famed for producing elixirs and tablets that would impart immortality, for foretelling future events, and even for transforming base metals into gold, so it is not surprising that they received royal support and patronage. Images of women as gurus and yoginis are often seen in 18th-century court paintings, and in several Tantric texts they are said to be as adept as their male counterparts.

Buddhist Tantrikas named these female practitioners dakinis and they soon assumed an important role in Tantric Buddhism, which flourished in eastern India from the c.7th to 12th century AD, spreading into Nepal and Tibet by the 8th century. Tantric Buddhism is more commonly known as Vajrayana ‘Thunderbolt Vehicle’, because it takes its teaching from the Vajramrita Tantra.

Two of the most popular Tantric Buddhist deities are Chakrasamvara and Vajrayogini, who are depicted in a close embrace on an 18th-century Tibetan thangka (a painting on cloth). The 12-armed, blue-skinned god Chakrasamvara is locked in coitus with the red-skinned goddess. He is decked out in long chains made of human heads and grinning skulls. Together, the Tantric couple trample on the Hindu deities Bhairava and Chamunda, who are seen as obstacles to enlightenment. Ramos notes:

The image is a perfectly composed yet explosive choreography of sexual energy and dynamic ferocity. The couple’s red-rimmed, wild eyes and laughing, fanged mouths suggest their immense power. They each have a third eye, a reference to their omnipotence over all three worlds: the world of desire, which is our own world; the world of form, with its heavens; and the world of formlessness, with its liberating emptiness…

Vajrayogini is an inflamed, blood-red colour, naked save for gold and bone ornaments. In her right hand she holds up a curved knife for hacking away at misplaced pride and the ego. Chakrasamvara holds up an array of symbolic objects, including an axe, trident, and noose, with which he extinguishes attachment, anger, ignorance and worldly desire…

Sex and death are inextricably entwined in this danse macabre. A garland of grisly decaying heads – each depicted with individual, almost humorous, character – hangs around Chakrasamvara’s neck and he carries a skull-cup bubbling over with blood… The interplay of sexual and violent symbolism in this and other yab-yum images speaks of the coming together of two uniquely Tantric forms of visual rhetoric. To represent the qualities of wisdom and compassion through images containing symbols of demonic wrath and military conquest not only evokes collapsing polarities but also highlights the belief that only the most ferocious deities can abolish the obstacles to enlightenment.

In the last gallery we see more recent depictions of Tantric deities. Here, we find a number of works by contemporary female artists, such as Sutapa Biswas’ 1985 mixed-media work, Housewives with Steak-Knives, which shows a bloodthirsty feminist version of the goddess Kali. In 1971, Kali – with her great, long red tongue – even inspired the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers logo, which is now seen on T-shirts across the world. In 1968, Mick Jagger had been the co-producer of a 40-minute experimental art film entitled Tantra: Indian Rites of Ecstasy. In the same year, the underground magazine Oz gave away a psychedelic pull-out poster entitled Tantric Lovers – showing a yab-yum couple surrounded by stylised, almost art nouveau swirls. By this time, Tantra was linked with anti-establishment movements calling for social, sexual, and political liberation, as well as spiritual freedom. And Tantra is still alive and well, being practised today in different parts of India.

As Hartwig Fischer, Director of the British Museum, says in his foreword to the book that accompanies the exhibition:

Tantra has been the subject of great fascination for centuries. However, it has often been misunderstood, particularly in the West where it is interpreted as a hedonistic guide to sex. Although the erotic plays an important role in Tantra, it should be understood as part of a broader philosophy of ritual transgression… Tantra challenged distinctions between opposites by teaching that all material reality is sacred, including the ‘forbidden’, which is ritually harnessed… The British Museum has one of the most comprehensive collections of Tantric material in the world and is in a unique position to present a history of Tantra through objects that challenge assumptions about it in stimulating ways.

This is exactly what Tantra: enlightenment to revolution sets out to do – and it succeeds.

Tantra: enlightenment to revolution is on show at the British Museum until 24 January 2021 (www.britishmuseum.org/exhibitions/tantra-enlightenment-revolution).

The accompanying book, Tantra: enlightenment to revolution by Imma Ramos, is published in hardback by Thames & Hudson in collaboration with the British Museum, at £30.