This is an extract of an article that appeared in Minerva 189. Read on in the magazine (click here to subscribe) or on our new website, The Past, which details of all the content of the magazine. At The Past you will be able to read each article in full as well as the content of our other magazines, Current Archaeology, Current World Archaeology, and Military History Matters.

Thomas Becket: Canterbury Tales

In 1170, Archbishop Thomas Becket was killed in his cathedral by knights linked to his former friend King Henry II. As the British Museum prepares to open a major exhibition exploring these events and their long legacy, curators Lloyd de Beer and Naomi Speakman tell us how a man who was both chancellor and turbulent priest was made into a revered saint and protector of the king.

Last year saw the 850th anniversary of a bloody crime in an English cathedral that would feature in art throughout medieval Europe and transform the city of Canterbury into a centre of pilgrimage: the murder of Thomas Becket. In May 2021, after delays due to the pandemic, the British Museum will open the first major exhibition on the life, death, and legacy of this figure, Archbishop of Canterbury and thorn in the side of King Henry II of England. Thomas Becket: murder and the making of a saint explores more than 400 years of history, drawing together objects from the British Museum’s extraordinary collection and 22 lenders from the UK and Europe. The exhibition charts Becket’s stratospheric rise to become one of the most powerful people in 12th-century England, first appointed royal chancellor to the young King Henry II and then, in 1162, Archbishop of Canterbury.

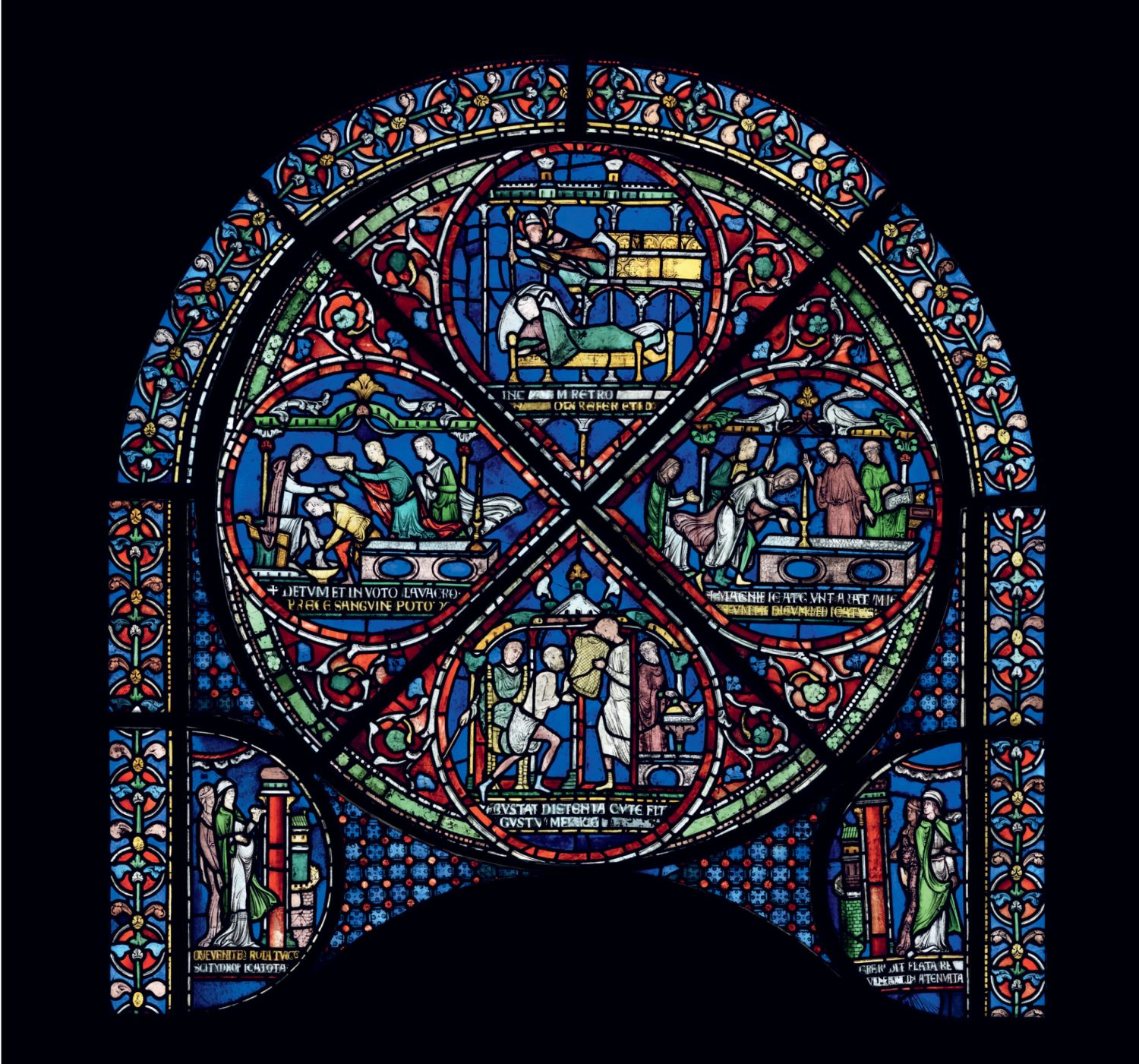

During his eight years as chancellor, Becket was a close friend of the king, part of his inner circle, but once he became archbishop his loyalties shifted and he began to oppose Henry’s authority. It led to their dramatic falling out, with dire consequences. Finally, in a shocking event no one could have predicted, Becket was murdered on 29 December 1170 by four knights from Henry’s entourage. Their violent altercation was depicted countless times over the following centuries in manuscripts, wall-paintings, stained glass, and sculpture. In recognition of his martyrdom, Becket was canonised by Pope Alexander III in February 1173 and was henceforth known as St Thomas of Canterbury.

We open Thomas Becket: murder and the making of a saint with a single object, a jewel-like casket enamelled in brilliant shades of blue, red, and green, made in Limoges, France, to contain a relic of St Thomas. It is the earliest, largest, and most magnificent of the early Becket reliquary caskets. On loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum, it was probably made around a decade after Becket’s death and shows the archbishop attacked from behind as he faces the altar. Two monks witness the scene and throw their arms up in horror. This dramatic moment sits at the heart of the exhibition, which examines the impact of Becket’s murder, from the establishment of Canterbury as a major pilgrimage centre to the destruction of St Thomas’s shrine and near total obliteration of his cult in the 16th century.

Moving back in time, Becket’s life story is revealed, beginning with his humble origins in London, his early career, and, finally, ending with his dispute with King Henry. Few surviving objects can be directly connected to Becket, apart from a number of manuscripts he collected and left to Canterbury Cathedral, which were later dispersed during the English Reformation in the 16th century. These include classical books such as Livy’s History of Rome, contemporary works such as John of Salisbury’s Policraticus (on loan from Corpus Christi College, Cambridge), and biblical texts such as an illuminated and glossed copy of the Gospels containing what is possibly the only known image of Becket made during his lifetime.

A tantalising link to the man himself comes from a single surviving wax impression made from his personal seal matrix. Becket probably carried the device from which the impression was made throughout his life, and would have used it to seal private letters and authorise legal documents. Measuring just a few centimetres in diameter the impression reveals aspects of Becket’s character. The legend SIGILLVM TOME LUND says that this is the ‘seal of Thomas of London’, as he was commonly known. He probably had the matrix made before he was appointed either chancellor or archbishop, when his title was formally changed to reflect his new status. For the centre of the matrix, Becket selected a beautiful Roman gem engraved with a standing figure, possibly Apollo. It reveals his interest the classical world and his choice of a fine ancient intaglio communicated to his peers, many of whom also had seals with reused Roman gems, that he was a learned man of the moment. Below the impression are traces of fingerprints. While we cannot be certain to whom these prints belong, they were made at the time of the document’s creation and are probably those of a clerk from Becket’s household staff, one trusted enough to handle his personal seal.