The rise of rulers

Extraordinary burials discovered in south-eastern Europe marked out individuals even at a time of egalitarian societies. Attila Gyucha and William A Parkinson guide us through spectacular finds from eleven countries that show how the elite grew their power in prehistory.

From the Neolithic to the Iron Age, the lands of south-eastern Europe played host to dramatic social changes as people made the transition from egalitarian farming communities to societies ruled by formidable chiefs and mighty kings and queens. Across a period of some 5,500 years, communities with increasingly complex political and economic inequalities developed, and an emergent elite grew their power and influence by exerting control over four focal aspects of prehistoric life: technology, trade, rituals, and warfare. For a new exhibition at the Field Museum in Chicago, we selected artefacts crafted during the Neolithic, Copper Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age (about 8,000 to 2,500 years ago) from the exceptionally rich archaeological heritage of south-eastern Europe to explore the importance of these four aspects in the evolution of social inequality and hierarchy in the Balkans and beyond.

The exhibition is an unprecedented intercontinental collaboration between the Field Museum and 26 museums in 11 south-east European countries: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, and Slovenia. It provides a unique opportunity for people from these countries to reflect on their common prehistoric past, for North American communities from these parts of Europe to come together and celebrate their common cultural heritage, and for people without direct connections to these regions to learn about and appreciate the long and rich cultural history of south-eastern Europe.

We begin this long history in a land before kings, with the early agricultural communities of the 7th to the 5th millennium BC. These Neolithic communities are commonly assumed to have been egalitarian, where social status was based on age and gender or was achieved through personal skills and actions, rather than being automatically passed on to the next generation. The mortuary record, however, suggests that some people were treated differently. Archaeologists have recovered burials in south-eastern Europe where the funerary process deviated from the regional norm and the number and quality of grave goods that were included were truly extraordinary. For example, a woman who was placed in a wooden coffin at the tell-centred site of Polgár-Csőszhalom in Hungary around 4900-4600 BC was buried with elaborately crafted objects, including arm-rings and necklaces made of Spondylus shells from the far-off Adriatic or Aegean Sea, indicating her important status within the community.

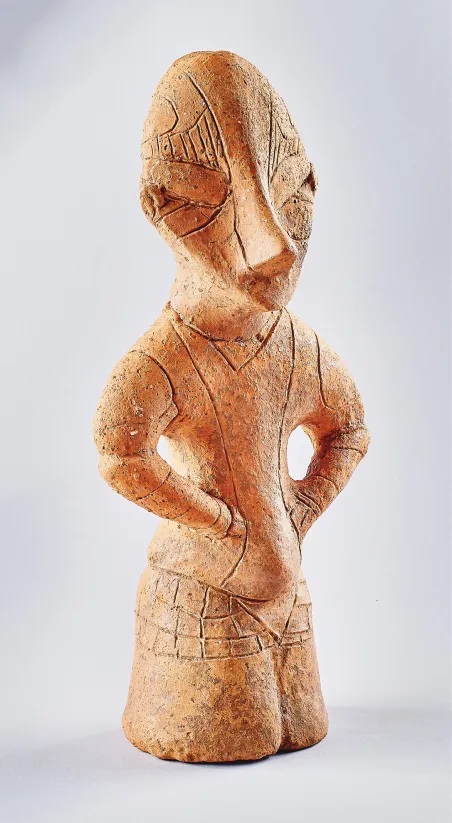

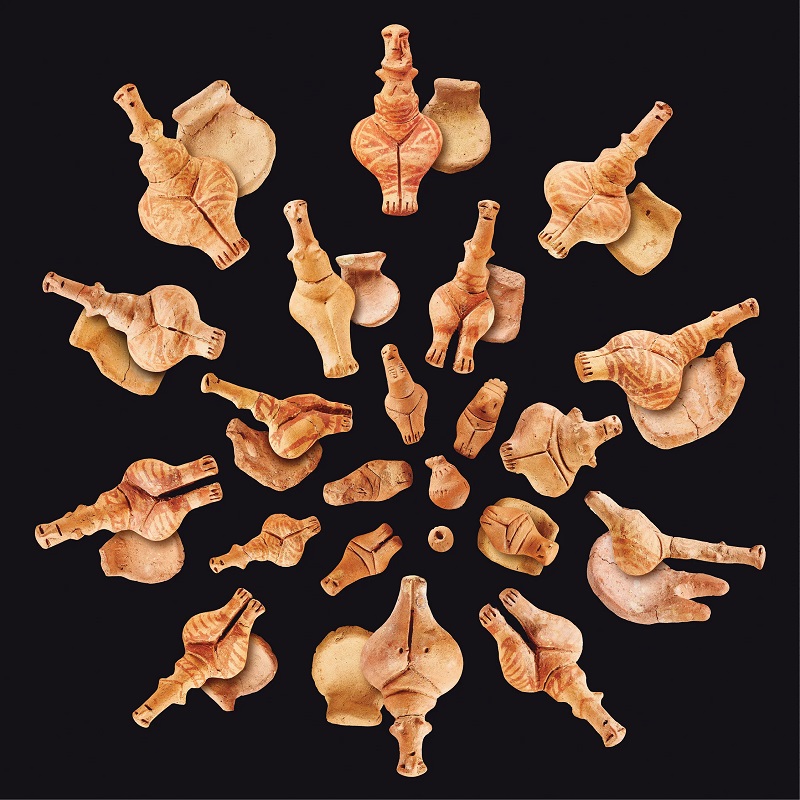

As well as grave goods, spectacular objects that would have been used as focal elements during the course of different ritual activities have been uncovered. Human figurines made of fired clay were common artefacts in many regions of south-eastern Europe, but their forms and decoration varied by region and period. A wide range of explanations has been proposed for the role of figurines in Neolithic communities: researchers have interpreted these objects as the representations of particular members of the community, ancestors, or supernatural creatures. Two examples from Kosovo, dating to 5200-4600 BC, represent the central Balkans, with characteristic facial features. In a few cases, figurines have been found as part of a larger assemblage of human depictions and other objects. In a possible sanctuary at Poduri, in Romania, 21 figurines of different size and decoration were recovered, along with 13 chairs, possibly representing members of the community, or perhaps a pantheon of gods.

The Neolithic was a dynamic era, with a trial-and-error approach taken to various aspects of life, including the organisation of settlements, subsistence, and social structure. People in south-eastern Europe enacted a wide range of responses to the challenges they faced, establishing institutions to secure social cohesion in regional and local communities, and developing innovative agricultural techniques to supply food to a growing number of people. The markedly diverse archaeological record testifies to the flexibility and adaptive capability of Neolithic communities across the region.

Over a thousand years after most people in south-eastern Europe had settled into a village lifestyle based on farming and animal husbandry, a series of technological and social changes occurred, heralding a first gilded age of sorts. Throughout the region, archaeologists have recognised a formal Copper Age that followed the Neolithic period and preceded the Bronze Age. Starting in the 5th millennium BC and ending at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, this era was characterised by the production of large copper artefacts, especially axes and adzes, and also by other transformations in social organisation, including the establishment of some of the first formal cemeteries in Europe.

The earliest use of copper in the region dates at least to the beginning of the Neolithic period, around 6200 BC, when early agricultural groups in the Danube Gorges in Serbia and Romania shaped and drilled chunks of ‘native’ copper metal and copper minerals, such as malachite and azurite, to make beads. Sometime around 5000 BC, metalworkers developed an innovation that would allow them to extract copper metal from copper minerals: smelting. This must have been seen by others as an almost magical act, carried out by specialists who possessed important knowledge.

After 4500 BC, artefacts made of smelted copper, including large mould-made axes and adzes, circulated throughout south-eastern Europe, linking the diverse farming communities from the Carpathian Basin to the Adriatic, the Aegean, and the Black Sea into networks of social interaction through which flowed ideas, information, and objects. Copper was not the only metal to be exploited during this time. Gold, panned from the rivers of the Balkans, also began to be used for crafting a wide variety of objects, including ornaments and status symbols.

In addition to innovations in metallurgy, the Copper Age witnessed the widespread adoption of a new funerary practice whereby the deceased would be buried in stand-alone cemeteries that were not directly associated with settlements. This created an important new venue for the performance of funerary rituals, which now would be carried out not only in front of the members of one’s own household and village, but on a regional stage as well.

During the Copper Age, the burial ritual started being used regularly to mark aspects of a person’s life other than gender, age, and personal skills, such as positions of rank and hierarchy within their community. Nowhere is this clearer than in the Copper Age cemeteries of Varna and Durankulak along the Black Sea coast of Bulgaria. In those cemeteries, during the middle of the 5th millennium BC, several hundred people were buried with unprecedented amounts of gold, copper, and other precious objects to mark social status. One burial at Varna contained almost a thousand gold artefacts and a variety of other objects made of exotic materials indicating the individual’s outstanding status and power in the region. Other graves contained artefacts but no dead bodies; these ‘empty graves’ or cenotaphs most likely represent people who died elsewhere. The assemblage of gold objects – including bracelets, dress appliqués, a miniature diadem, pendants, and a sceptre – from Grave 36 at Varna was part of a cenotaph, probably associated with a young man as suggested by other burials in the cemetery.

Another tradition that evolved during the Copper Age was the burial of groups of objects in hoards. Sometimes, these caches of objects may have been functional – people burying valuable things in troubled times so others would not find them – but in many cases hoards were ritually placed into the ground to recognise specific events, moments, deities, or people. Based on later examples, we presume that some hoards commemorate alliances or perhaps the memory of a leader.

During the Copper Age, major innovations were introduced in south-eastern Europe, including the wheel and the wagon. Their importance for the local communities is indicated by wagon models, such as the one from Szigetszentmárton in Hungary. People from the steppe may have brought domestic horses with them during the transition between the Copper Age and Bronze Age, and they became important symbols of power and prestige across south-eastern Europe in the millennia to come. In fact, horses might have played a significant role in laying the foundation for dramatic changes in leadership and hierarchy that occurred throughout the region during the Bronze Age.