Painting Pompeii

Richly painted frescoes enlivened the often dark and claustrophobic rooms of Roman houses. How was this interior world of colour created? Dalu Jones celebrates the triumph of Pompeii and Herculaneum’s frescoes.

‘…fleeting as thought and as beautiful as if drawn by the hand of the Graces…’

JOHANN JOACHIM WINCKELMANN (1717-1768)

Fragments of ancient Roman frescoes have been uncovered across the Empire, but it is the more substantial and better-preserved sections from the cities around the Bay of Naples, sealed for centuries under the debris from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, that really capture the imagination. New discoveries from Pompeii continue to astound and add to the picture of the rich decoration of private homes and public eateries in the Roman world, their surfaces covered with vivid mythological narratives, erotic scenes, idyllic landscapes, and imitations of more costly marble. Indeed, it is from frescoes in and around Pompeii that scholars came to define the four styles that chart the development of Roman wall painting.

The wall paintings found in these buried cities are once again the subject of a major exhibition: I Pittori di Pompei (The Painters of Pompeii) at Bologna’s Museo Civico Archeologico. This time, however, the focus is on the painters who created these extraordinary artefacts in Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Stabiae rather than on the cataclysm that obliterated them and their work. Three hundred years after the first discovery of these towns, researchers are able to provide precise information on the technical details of the famous Roman wall paintings that survived the eruption in AD 79, shedding light on the painters themselves, their tools, the pigments they used, and the pattern books that probably circulated within the society they lived and worked in and which sponsored them.

There are more than 100 painted panels in the exhibition from the collection of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, and they give an overview of production in the late Republic and the early Empire, from the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD. Many of the panels were cut out from the walls of the then newly discovered buildings of the lost cities of the Bay of Naples in the 18th century. They were framed and hung as standalone paintings in the summer palace of the Bourbon royal family at Portici, close to Herculaneum. Such was the success of these paintings that the king had to take measures to prevent theft from excavated sites and the widespread practice of manufacturing alluring forgeries, some of which mixed styles and materials such as mosaics in relief.

Because of the lack of surviving easel paintings – with the exception of the outstanding, vividly realistic Fayum portraits – frescoes give us a clear and vital indication of the high-quality and sophistication of Roman painting in the Republican and Imperial centuries. The Fayum portraits, painted on wooden boards to cover the faces of mummies in Roman Egypt between the 1st century BC and 3rd century AD, have an almost-unsettlingly lifelike quality and a powerful intensity that puts them on par with some of the most-arresting masterpieces of Renaissance and later portraiture. The same liveliness and keen observation characterise the best of the Roman portraits sculpted in marble or painted on glass, as well as those inserted as medallions in the painted decoration of some of the houses in Pompeii. A portrait of an actor looking at the mask he will be wearing on stage is a good example of the Pompeian artists’ capacity for immediacy.

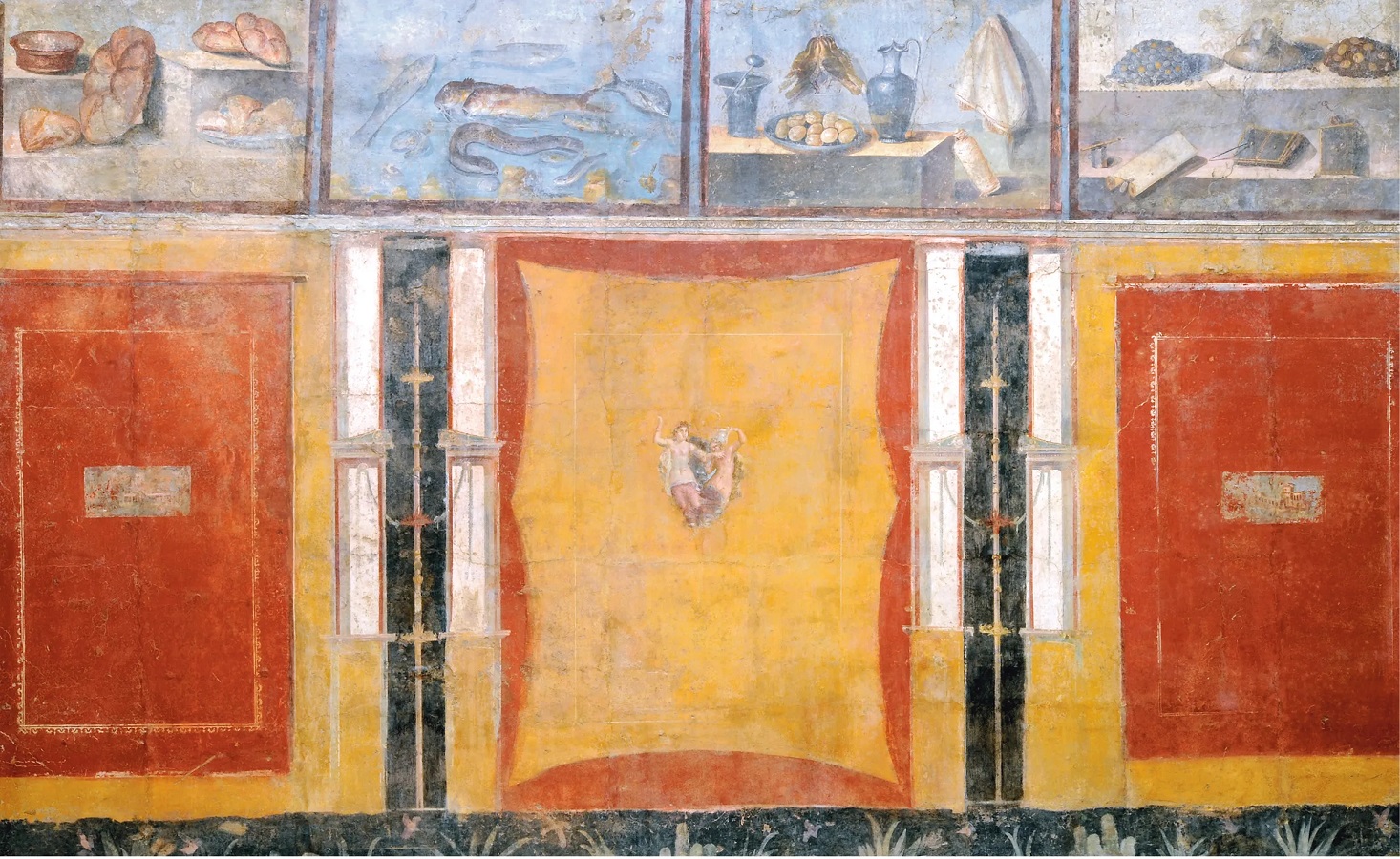

An interesting example of this Fourth Style in the exhibition is a complex, theatrical trompe l’oeil composition, enhanced with polychrome stucco, that was found in the tablinum (office) of the House of Meleager in Pompeii. The scheme includes a framed scene showing Io (the nymph and princess pursued by Zeus, who later turned her into a white heifer to avoid his wife Hera’s suspicion) and Argus (who in some versions of the myth is a many-eyed giant, appointed by Hera to watch over Io). The overall design of this flamboyant frescoed room also included landscape scenes and still lifes characteristic of the latest and most elaborate of the four Pompeian styles. Another beautiful framed scene comes from the adjoining atrium. It depicts a regal Dido, enthroned. This fabled founder of Carthage has a black servant holding a rhyton by her side and another woman nearby wearing small tusks in her hair. We are probably meant to understand these as elephant tusks, and thus the woman probably represents Africa. The ship of the Trojan prince Aeneas, driven by destiny to Italy, is already sailing away in the distance.

Much is understood about the subject of Roman wall painting thanks to past generations of antiquarians and archaeologists such as Mau, but there is still much to explore, especially in light of fresh discoveries made in different areas of the Roman Empire and in the still partially unexcavated Vesuvian cities. In August 2022, an unexpected discovery was made at the 1st-century AD ruined temple at Cupra in central Italy: here, archaeologists found that the temple’s walls and a high ceiling had been painted in bright colours in the Third Pompeian Style, known to be popular further south. The frescoes found in recent years in Pompeii include the engaging images of a sea nymph, rooster, and ducks decorating the outer walls of the counter of a thermopolium (a fast-food shop); a gory depiction of gladiators from a stairwell that possibly lead to a brothel; and, from the bedroom walls of a private house, the mythological tale of Zeus in the shape of a swan, seducing the mortal Leda. This last fresco is just the latest of the many erotic scenes found in situ in Pompeii or hung in the archaeological museum in Naples.

Because of their subject matter, these paintings, as well as erotic sculptures and phallic objects, were the cause of much controversy and were shown only under special circumstances, until, in 2000, the ‘obscene’ collection in Naples was opened without limits. By taking the artefacts out of their original context, their meaning and function was often misinterpreted. By the mid-19th century, a special Gabinetto Segreto degli Oggetti Osceni (Secret Cabinet of Obscene Objects) at the Museo Borbonico (as the National Archaeological Museum of Naples was then known) was only accessible to ‘people of mature age and respected morals’, following the suggestion of the future king of the Two Sicilies, Francesco I. It was believed that to be able freely to view such objects would corrupt the observer – the working classes, women, and children especially.

What do we know of the pictores themselves, the painters of these and other scenes? Roman artists were almost always anonymous and their output often considered not as individual works of art on their own merits but merely as part of the overall decoration and furnishing of a house or a public building. Roman wall painters were classified and hired according to their skills, and paid accordingly. The pictor parietarius (wall painter) was responsible for the backgrounds and the borders, and left spaces for the centrepieces to be painted on the wet plaster by the pictor imaginarius (figure painter).

The pictor imaginarius, who according to a much later AD 301 edict under Diocletian was to be paid twice the fee of the pictor parietarius, would fill these spaces with more complex scenes, generally inspired by mythology, or with landscapes and still lifes. A variety of landscapes appear in Roman frescoes, but they are somewhat limited because they mainly served to create a backdrop of recognisable landmarks where certain events might take place. As the 1st-century BC architect Vitruvius noted in his De Architectura, they included features such as mountains, rivers, groves, fountains, seashores, harbours, and shepherds with their flocks. The still lifes that would be added by a pictor imaginarius were usually framed at the top of walls. Known as xenia, a Greek word referring to offerings to guests, they were meticulous renderings of fish and fowl, eggs and fruit, often displayed on shelves among metal and glass containers. They were an illustration of the generous attitude of the owner of the house towards visitors – and further evidence of his wealth.

This is an extract of an article that appeared in Minerva 199. Read on in the magazine (click here to subscribe) or on our new website, The Past, which details of all the content of the magazine. At The Past you will be able to read each article in full as well as the content of our other magazines, Current Archaeology, Current World Archaeology, and Military History Matters.