Knossos

Myth surrounds the famous Palace of Knossos, but there is much more to the Cretan site than the fabled Minotaur and King Minos. A new exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum delves into the archaeology of the Minoan site and the later work that is reshaping Arthur Evans’ controversial interpretations, as Maev Kennedy finds out.

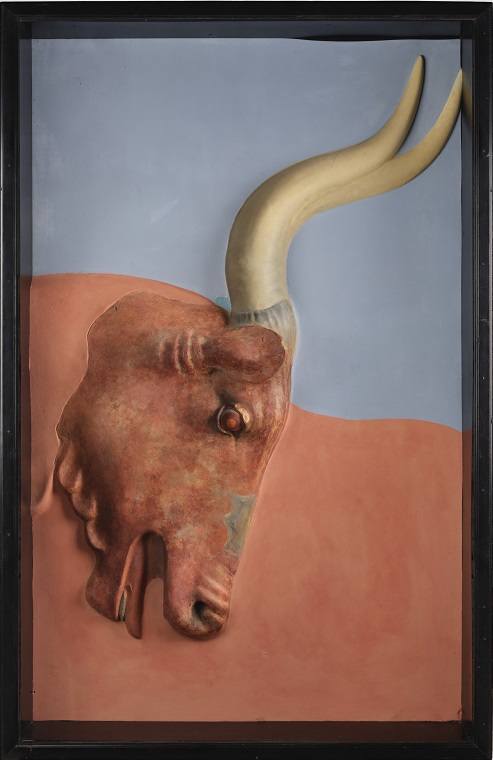

Replica of the bull’s head fresco from the North Entrance of the Palace of Knossos. Painted plaster, early 20th century. Size: 88 x 136cm (Image: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

The Palace of Knossos, on a low hill near the modern city of Heraklion, is the most renowned tourist attraction in the island of Crete, a World Heritage Site, and the second most-visited archaeological site in Greece after the Parthenon. As the world woke up and tourism recovered after the pandemic, visitors queued for hours for admission last summer – a record 8,000 on one day – entranced by the legends of King Minos and his happy world of beautiful youths processing among flowering plants and butterflies, dancers soaring in daring leaps over the backs of mighty bulls, and gorgeously costumed bare-breasted goddesses fearlessly holding snakes.

The major exhibition about Knossos and the Minoan world opening at the Ashmolean in Oxford in February (Labyrinth: Knossos, myth and reality) is surprisingly the museum’s first, even though it holds the most important collection outside Greece, and its own history is intimately connected with the archaeology of the site. Sir Arthur Evans, the museum’s keeper in 1884-1908, led the transformation of the Ashmolean from natural history to the art and archaeology museum in an imposing building it is today. He was also the scholar and archaeologist who helped create the modern fame of Knossos, a Bronze Age palace complex wreathed in later Greek legends telling of the labyrinth created by Daedalus to house the Minotaur, the monstrous offspring of a queen and a bull, the sacrificial offerings of Athenian youths to said creature, and the rescue of the Athenian hero Theseus by the beautiful – and later abandoned – Princess Ariadne, with the aid of the ball of thread.

Ancient Greek coin from Knossos showing the Labyrinth. Silver, c.300-270 BC. Size: 2.6cm diameter (Image: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

These legends fascinated centuries of travellers who were shown a stone quarry with its myriad tunnels and dead ends as the site of the mythical labyrinth. Their power endures, and the exhibition includes 20th-century images of the Minotaur by Pablo Picasso and Michael Ayrton, and the labyrinths created for London tube stations by Turner Prize-winning artist Mark Wallinger.

In the early 20th century, it was the beauty of artefacts more than 3,500 years old, excavated from March 1900 by Evans and his team, that astonished and enthralled the world. They included spectacular jewellery; eggshell-thin ceramics; elegantly stylised carved or painted images of humans, animals, and sea creatures on gemstones, cups, and vases; and the vivid frescoes, which seemed so contemporary that one woman with kohl-lined eyes, reddened lips, and whitened skin, hair tumbling in ringlets around her neck, was dubbed ‘la Parisienne’. Thousands flocked to exhibitions at the Royal Academy, replica artefacts were sent on world tours, and Evans’ own three-volume account of his work became a bestseller.

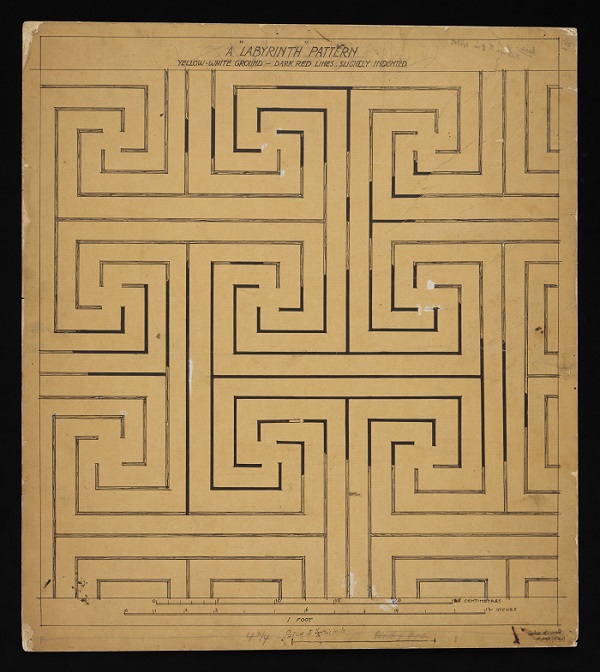

Reconstruction drawing of the labyrinth fresco from Knossos. Early 20th century. Size: 57 x 47cm. (Image: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

Since childhood, Evans had very poor distance sight, but at close range could see intricate details in sharp relief, such as the beautiful carvings on seal stones from Knossos and other Minoan sites on Crete. Most are so small, packed into a space no bigger than a fingernail, that the images are barely visible to the naked eye. In the late 19th century, when he looked at the first tiny carvings to arrive at the Ashmolean, Evans saw a whole new world in the flowers, fish, bulls, and graceful human figures – a great and brilliant civilisation older than Classical Greece. Soon he would set out to visit the island for himself – this was 1894 – collecting antiquities from village shops wherever he travelled. Evans, independently wealthy as the son of the gentleman scholar and businessman Sir John Evans, would eventually buy – for the equivalent of £60,000 today – excavate and restore the site of Knossos, creating its fame and lasting controversy.

Fragment of fresco with labyrinth design, from the Corridor of the Labyrinth Fresco, Palace of Knossos. Painted plaster, 1700-1600 BC. Size: 21.5 x 20cm (Image: © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Heraklion Archaeological Museum)

Largely thanks to his work, and despite mistakes in interpretation still being unpicked by scholars, Knossos became one of the most renowned archaeological sites in the world. Annual excavations are still uncovering more of the Minoan civilisation which flourished for millennia rather than centuries, its palaces and palatial buildings decorated with beautiful frescoes, wonderful ceramics – and sophisticated plumbing. A 3D-printed model has been specially created for the exhibition to attempt to make Knossos slightly easier to understand. It may have been a palatial complex rather than a true palace, but it was certainly labyrinthine, built and rebuilt over millennia with up to a thousand rooms stacked four storeys deep.

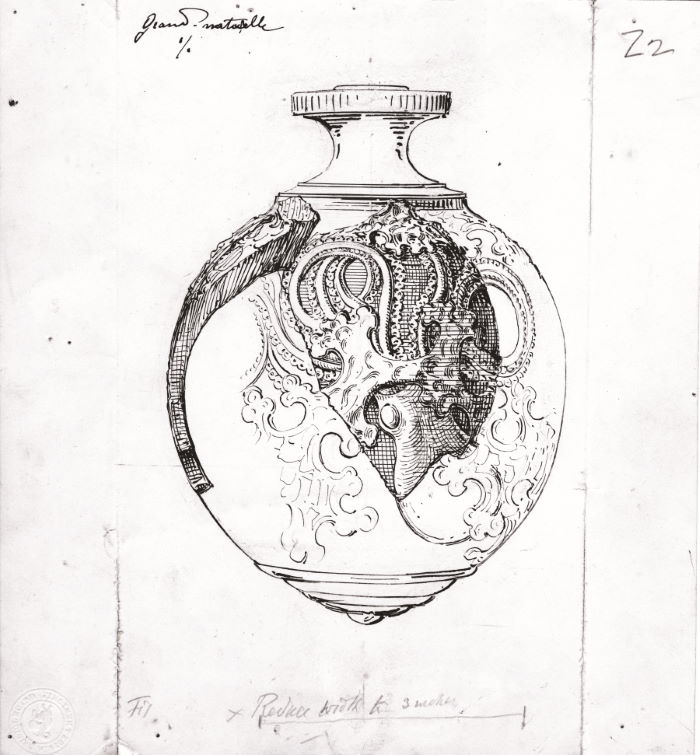

Fragment of the ‘Ambushed Octopus’ stone rhyton, from the Throne Room of the Palace of Knossos. Chlorite, 1600-1450 BC. Size: 7.9cm high. (Image: © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Heraklion Archaeological Museum)

The Ashmolean holds all of Evans’ now fragile excavation notes and drawings, as well as hundreds of objects he collected, including the duplicate and less important objects he was allowed to bring back to England and the replicas he commissioned of the most precious artefacts, which could not be exported. The exhibition is speeding up the digitisation of the archive, and many newly conserved objects and documents are being brought out of the Oxford stores to be united with loans from the museum in Heraklion that have never left Crete before. In some cases, the real objects will be seen with Evans’ drawings for the first time since they were excavated, including one of the beautiful bull’s head rhytons – containers for ritual libations or offerings.

Reconstruction drawing of the ‘Ambushed Octopus’ stone rhyton. Ink on paper, undated. Size: 22 x 20cm. (Image: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

Evans’ work was controversial in his time and since. Many major sites would now be backfilled to protect the original fabric after excavation, but much of what visitors see today at Knossos is a recreation of what Evans was convinced had been there: he termed his interventions ‘reconstitution’. While excavation continued, his workmen rebuilt entire rooms, among them the brilliantly coloured, frescoed Throne Room dating from the 15th century BC, giving full-height columns, walls, and ceilings to spaces shown in excavation photographs as roofless outlines full of rubble from collapsed upper storeys. Major restoration work has recently been needed on reconstructions now over a century old, with concrete walls and ceilings originally believed indestructible but actually decaying because of corroding iron reinforcing-rods.

Bull’s head rhyton from the ‘Little Palace’ at Knossos. Ceramic, 1450-1375 BC. Size: 20.2 x 11.3cm. (Image: © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Heraklion Archaeological Museum)