I, Enheduanna

Enheduanna, high priestess at the ancient city of Ur, is thought to be the world’s first named author. She was a poetic innovator, but she was not alone in Mesopotamian history as a prominent or a literate woman, as Lucia Marchini learns from Sidney Babcock.

Sometime in the 23rd century BC, a writer composed a series of hymns devoted to the different gods worshipped in the temples of 36 cities across Mesopotamia. These Temple Hymns were signed off with the following lines:

The compiler of the tablets (is) Enheduanna.

My lord, that which has been created (here) no one has created (before).

This declaration of originality and authorship, and lines from another poem, ‘The Exaltation of Inanna’, give us the name of what is thought to be the first known writer: Enheduanna.

Though the name Enheduanna is a Sumerian one literally meaning ‘high priestess, ornament of heaven’, the priestess on whom it was bestowed was the daughter of King Sargon of Akkad (c.2334-2279 BC). Living around 2300 BC, Enheduanna was appointed high priestess, or en, of the moon-god Nanna in Ur, after her father unified the (northern) Akkadian and (southern) Sumerian city-states in what is now Iraq. Nanna, whose shrine was part of a huge ziggurat, was the patron deity of Ur, and so proper worship was vital for the city’s wellbeing. With a new Akkadian Empire on his hands, deploying his daughter to this important position in the significant Sumerian city was one way for Sargon to lend legitimacy to his rule in the south, promote a sense of unity, and elide the religious and administrative spheres.

Most texts were written by scribes, and so the priestess Enheduanna was stepping into an unusual role as poet. There are no surviving original versions of the works attributed to her, and some scholars have disputed her authorship. The poems became canonical works, set texts copied by scribes centuries later as part of their training. As well as giving us numerous versions of the texts, this practice of copying points to the high place the poems held in Mesopotamian culture, securing Enheduanna’s legacy for generations to come.

Sidney Babcock, curator of She Who Wrote, a new exhibition on Enheduanna and women in Mesopotamia at the Morgan Library in New York, explains the questions of attribution: ‘We only have copies and there are certain things that have crept in over the years, which is what happens with copying. People have been debating those on and on and on, and unfortunately some scholars have even questioned her authorship.’

‘There are those of us who don’t agree with that. She says it, why not give it to her? We have her image, we have her name. And when you read the poetry, this is a very strong personality that comes through, particularly in the “Exaltation”.’

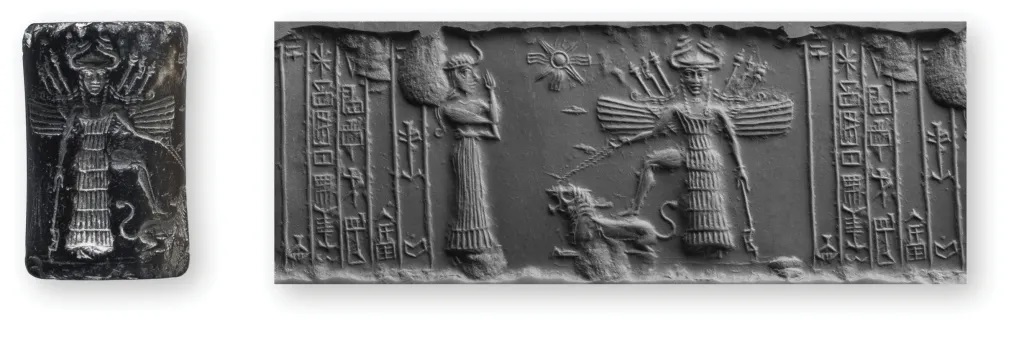

As well as these copies on cuneiform tablets, other physical evidence attests to Enheduanna’s important status. Cylinder seals in deep blue lapis lazuli and a seal impression on a fragment of clay (which may have been attached to a vessel to validate its contents) identify Enheduanna, daughter of Sargon, and members of her staff – scribes [x]-kituš-du and Sagadu, estate manager Adda, and hairstylist Ilum-pāl[il]. As high priestess, she would have had numerous personnel to oversee.

The priestess is identified again on an alabaster disc discovered in fragments at the gipar, the residence of the high priestess of Nanna at Ur. Enheduanna is both named in an inscription on the back and depicted on the front in a scene by a ziggurat-like building. Wearing a long garment with layers of fluid flounces and a headdress (attributes that we see in other images of high-ranking priestesses), Enheduanna is pictured slightly larger than the attendants accompanying her, and, as Babcock points out, ‘looking up into the numinous realm’ as she presides over the pouring of a libation at the altar in front of the building.

This Disc of Enheduanna (c.2300 BC) is fragmentary and the inscription on the reverse is only partially preserved. A copy of the full inscription, however, has been found on an Old Babylonian (c.1894-1595 BC) tablet, which clearly identifies Enheduanna, ‘priestess, wife of the god Nanna, daughter of Sargon, king of the world’, as the dedicator of the disc, and shows that it was known of for several centuries.

Enheduanna has left us with more than just her name to get to know her and the world she lived in. Her poetry is important in presenting a blending of Akkadian and Sumerian cultures. Writing in Sumerian, in the Sumerian city of Ur, she uses the name of the Sumerian queen of heaven, the goddess of sexual love and fecundity, Inanna, but essentially gives her the attributes of the formidable patron deity of the Akkadians, the goddess of war Ishtar. By conflating these two religious identities in ‘The Exaltation of Inanna’, Enheduanna seems to have been taking an active role in her father Sargon’s great unifying quest in the first Mesopotamian empire.

Verses from ‘The Exaltation of Inanna’ survive in around 100 copies from cities around Mesopotamia – including a trio of tablets dating from c.1750 BC, possibly from Larsa, that preserve the hymn in its entirety. In 153 lines, the poet-priestess praises Inanna (imbued with the warlike qualities of Ishtar) at length. The poem is also powerfully personal. ‘It is arguably Enheduanna’s most important work, where she herself steps forward and for the first time someone writes in the first person,’ says Babcock. ‘She basically invents autobiography and her strong personality clearly comes through.’

This is an extract of an article that appeared in Minerva 198. Read on in the magazine (click here to subscribe) or on our new website, The Past, which details of all the content of the magazine. At The Past you will be able to read each article in full as well as the content of our other magazines, Current Archaeology, Current World Archaeology, and Military History Matters.