Converting the Caucasus

According to legend, a king who had been saved after being turned into a boar ordered the conversion of Armenia to Christianity. From these royal beginnings came fights between crown, clergy, and defenders of different creeds. Christoph Baumer takes us on a journey through the ecclesiastical conflicts of the Caucasus and to its magnificent early churches.

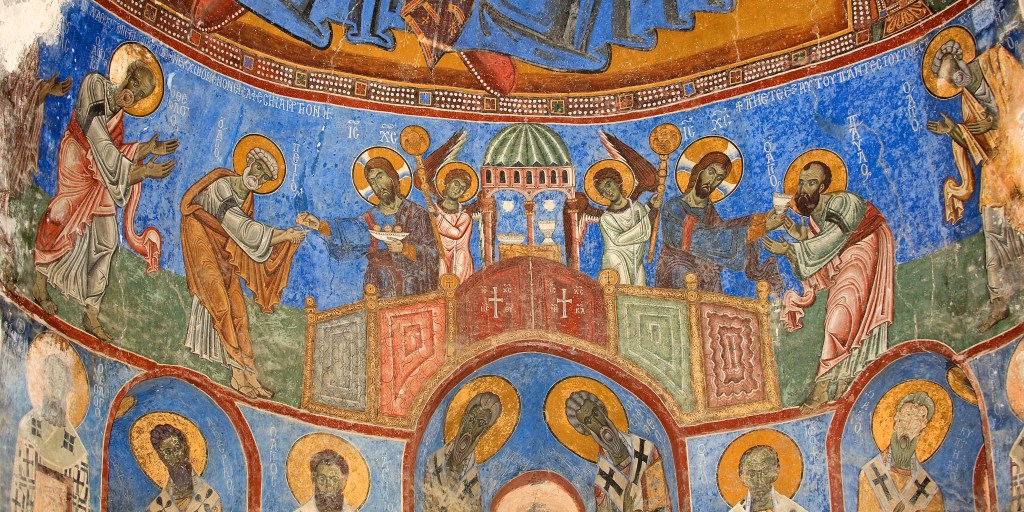

Located in the Caucasus, a meeting point between Europe and Asia, Armenia boasts of being the first state to have adopted Christianity – around the year AD 314 – followed by its neighbour Georgia twenty years later. Various encounters between this region’s indigenous peoples and many other groups, among them Romans, Persians, Greeks, Scythians, Arabs, Turks, and Mongols, brought new languages to the Caucasus and new religions like Christianity, which led to centuries of building chapels, cathedrals, and monasteries across the landscape of narrow mountain valleys that stretch between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea.

Christianity did not spread in a religious vacuum, but in the Caucasus encountered Iranian beliefs that were strongly adapted to suit local traditions. These local beliefs differed markedly from the purist reforms of Zoroastrianism implemented by high priest Kartir in the second half of the 3rd century AD. According to the Armenian historians Agathangelos (writing around 460) and Moses Khorenatsi (late 8th/9th century), the pre-Christian Armenian pantheon counted eight major deities: the creator god Aramazd (Zeus), derived from Zoroastrianism’s Ahura Mazda; Anahit (Artemis), the goddess of fertility and wisdom; Nanē (Athena), the personification of war and wisdom; Mihr (Hephaistos), the god of truth and the sun, related to Mithra; Vahagn (Heracles), who corresponded to Verethragna, the Iranian god of war, fire, and thunder (in the Svaneti region in Georgia he continued to be venerated by Christians as an intrepid slayer of enemies of the Church under the guise of Archangel Gabriel); Tir (Apollo), the god of oracles who recorded all the deeds of humans; the astral goddess Astalik (Aphrodite); and, lastly, Barshamin, the weather and sky god, who corresponded to Baal Shamin and was venerated in Syria and northern Mesopotamia. The fact that seven of these eight deities bore Iranian and Greek names reflects the political situation of Armenia, which (with interruptions) was a Parthian–Roman condominium, a territory in which these two empires both held power, from the 1st to 4th century AD.

Traditionally, the historiography of Armenia, Caucasian Albania (roughly today’s north-western Azerbaijan), Iberia (also known as Kartli, central Georgia), and Lazica (western Georgia) was influenced by the political conditions in the respective kingdoms and by the ethnically defined church organisations. Early texts ignored the missionary activities from Syria and Cappadocia during the 3rd century, and hagiographies initially focused on the reign of Emperor Constantine (r. 306/324-337). They assigned the leading role in the region’s Christianisation to Armenia and credited missionising the whole South Caucasus to one figure: St Gregory the Illuminator (d. 330/331).

According to legend, this Gregory, the son of a prince of Armenia’s ruling Arsacid dynasty, refused to offer sacrifices to the fertility goddess Anahit. King Trdat IV (r. 298-c.330/331) threw him into a dungeon, over which the monastery of Khor Virap was later built, in 1661-1662, on the ruins of a 7th-century chapel. About 12 or 13 years into Gregory’s imprisonment, St Rhipsime – along with 36 other virgins – sought refuge in Armenia from the persecution of Christians by Emperor Diocletian (or, rather, by Maximinus Daia). When Rhipsime rejected the king’s advances, she and her companions were martyred. Similar to the fate of King Nebuchadnezzar in the Bible, Trdat was then transformed into a boar. The turning point came when his sister advised him to free Gregory, who promptly healed him. Trdat and his family subsequently converted to Christianity. The king instructed Gregory, who was consecrated bishop in 314, to convert all Armenians and build churches. Moreover, he placed his troops at Gregory’s disposal to ‘convince’ recalcitrant nobles and destroy pagan temples.

The Armenian Apostolic Church sets the date for the conversion of Armenia as the year 301, which is too early. It is highly unlikely that Trdat, a client of Rome, would have dared to adopt Christianity when his overlords Emperor Diocletian, co-Emperor Galerius, and Caesar Maximinus Daia were pursuing a strict anti-Christian policy. Agathangelos confirmed that Trdat was at first an obedient client of Diocletian and Galerius. When their successor Constantine began to embrace Christianity from 313 onward, however, Trdat instrumentalised the novel monotheistic faith to unite his unruly nakharar (nobles) into a single monarchy under the auspices of the new religion. At the same time, the confiscation of the pagan temples’ wealth filled the treasury and financed the construction of churches.

Nevertheless, both Constantine and Trdat failed to anticipate that the hierarchically organised Christian clergy would not only soon refuse to submit to worldly power, but also, once becoming the state religion, strive for supremacy and challenge the rulers’ authority. Trdat was forced to compromise with the nakharar who had often controlled the pagan temples. He agreed to select bishops from among their ranks, which meant that ecclesiastical offices and church possessions remained part of the inheritance for noble families. The Gregorids, for instance, thus became one of the most powerful Armenian families. Bishops did not represent cities or state provinces as in the Roman Empire, but pursued the interests of the landed nobility.

Thirty years after Trdat’s conversion, the smouldering conflict intensified. Armenian kings had chief prelates murdered, while leading nakharars, both Christians and Zoroastrians, betrayed their Christian ruler by allying themselves with Byzantium’s arch enemy, the Persian Sassanids. After Byzantium and Persia divided Armenia in 387, these conflicts came to a head in 428: the leading Armenian nobles entreated the Sassanid Shah Vahram V to depose their king and abolish the Armenian monarchy. Vahram was only too happy to help and installed a Persian provincial marzpān (governor). While it is true that Christianity would eventually emerge as a cornerstone of national identity, the saga of a unified Christian bulwark against first the Zoroastrian Persians and then the invading Arabs is apocryphal.

This is an extract of an article that appeared in Minerva 194. Read on in the magazine (click here to subscribe) or on our new website, The Past, which details of all the content of the magazine. At The Past you will be able to read each article in full as well as the content of our other magazines, Current Archaeology, Current World Archaeology, and Military History Matters.