The archaeologist of artists

Dominic Green looks at the sensual paintings of the acclaimed Victorian artist Lawrence Alma-Tadema currently on show at Leighton House in London

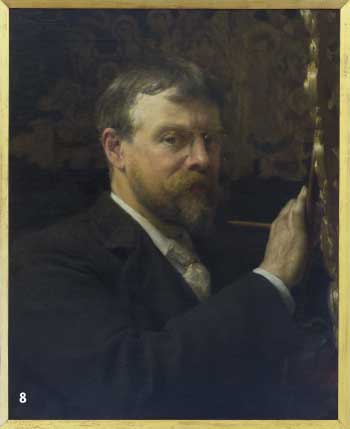

From his election as Royal Academician in 1878 to his death in 1912, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema's carefully structured canvases (1 to 8) – elegant in architecture, romantic in narrative, lush in pigment and rich in sensuality – defined the Graeco-Roman past for most high- to middle-brow members of the public. He was well paid, popular and – despite John Ruskin's reservations – tolerated, if not praised, by the critics. But, when Victorian art fell out of fashion during the early 20th century, the reputation of Alma-Tadema declined, too.

In 1955, an anonymous couple bought Alma-Tadema's lavish processional The Finding of Moses, 1904 (3) from a London dealer – for its frame. According to legend, the buyers left the canvas in the alley outside the gallery with the rubbish. Five years later The Finding of Moses found its way back to Christie's, but neither it nor its new frame could find a buyer. Then, in the 1960s, the hedonist hipppies ransacked the Victorian dressing-up box and brought 19th-century art out of the attic and it became fashionable again.

By 1973, The Finding of Moses was on show at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, one of many works by Alma-Tadema amassed by Allen Funt, the producer of the television comedy show, Candid Camera. Although the Met rather disowned its show, entitling it Victorians in Togas, like Constantine's Rome, Alma-Tadema continued to rise from his fall. In 2010, Sotheby's in New York sold The Finding of Moses to an anonymous buyer for $35,922,500.

This year, Alma-Tadema returns in triumph to London after a century of exile. After opening in Holland at the Museum of Friesland (near his birthplace in Leeuwarden), then progressing to the Belvedere at Vienna, Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity opens at Leighton House Museum on 7 July. This is his first major London show

since the posthumous tribute of 1913. Arise, Sir Lawrence!

Lourens Alma Tadema was born in 1836, a notary's son from rural Friesland. In 1852, aged 16, he left for the Royal Academy of Fine Arts at Antwerp, and an apprenticeship under two Belgian painters. From Jan August Hendrick Leys, he learnt the art of staging a dramatic tableau

– the placement of characters to reflect emotional dynamics, the use of oblique perspective to suggest that the viewer has just entered a private narrative, and deployment of historical detail to weave the eye into the image. From Lodewijk Jan de Taeye, Alma Tadema learnt the techniques of the northern Old Masters – the emotional intimacy of the shadowed interior, the use of lighting to heighten domestic stillness into a quiet epic.

Alma-Tadema launched himself in the 1860s with Merovingian scenes for patriotic Belgians, but he was already looking south. The story of The Education of the Grandchildren of Clotilde, 1861, is bloody, like the Dark Ages – Clotilde is teaching her grandchildren to throw axes, so that they can avenge their father – but the scene is staged before Corinthian capitals.

Dubbed 'the archaeologist of artists' by the American critic Georg Ebers, in The Nation in 1886, Alma-Tadema had experienced archaeology at firsthand. In 1863, he and his wife, Pauline, had honeymooned in Italy. As the newly-weds wandered through the excavations at Pompeii, he discovered his stage, the urban fabric of the 1st century AD. Lourens drew Pauline sitting on the steps of the Odeon, the small comedy theatre – one of first placements of a modern character in an ancient Roman drama. In the watercolour Pauline at Pompeii, his wife is in the rear corner of a domestic interior. Her red dress merges with the red walls, and her black bonnet is a monochrome counterpoint to the white marble table in the foreground. It is as though Lourens was working out how to blend living subjects with undying stone and marble.

Alma-Tadema also took photographs of the ruined city's exposed interiors, made some drawings of domestic architecture and took precise measurements of marble slabs and decorative paintwork.

A black-and-white photograph shows the artist on honeymoon with his measuring tape, crouched in the corner of the House of Sallust as he examines a marble skirting. Later, he collected fabrics, which he catalogued, complete with observations of how each type of cloth fell into its own kind of pleats.

The Roman and Egyptian paintings that followed are as much the work of an architect, or a novelist, as a painter. Like a neo-Gothic building or an historical novel, they reflect the era of their creation as much, if not more, than the era of their setting. The subjects of Glaucus and Lydia (1867) are characters in Edward Bulwer Lytton's bestselling novel of 1834, The Last Days of Pompeii.

Bulwer Lytton had himself been inspired by seeing Karl Briullov's painting The Last Day of Pompeii, 1830–33, while on holiday in Rome. Briullov's canvas is a Romantic apocalypse: as the Pompeiians flee the fire in darkness. Alma-Tadema's subject is a domestic interior, placid on the surface, but dramatically disturbed by a narrative framework of deep romance and apocalypse.

In Bulwer Lytton's novel, Glaucus, a noble Athenian rescues Nydia, a blind slave who is expert in tying floral wreaths for lovers. Alma-Tadema depicts Glaucus reclining on a couch, watching Nydia, but not seeing that she loves him, and that the wreath she is tying is for him. When Vesuvius erupts, Nydia will save Glaucus and Ione, the beautiful and aristocratic Greek woman he loves. Then Nydia will walk into the sea, preferring death to unrequited love.

Alma-Tadema's public already knew this because they had read Bulwer Lytton's novel. They might also have seen the American Neo-classicist Randolph Rogers' sculpture Nydia, the Blind Flower Girl of Pompeii (1854), in which Nydia cocks an ear to the coming eruption. Rogers' Nydia, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, became so popular that she was duplicated in some 77 casts.

The public might even have visited Pompeii and heard tourists reading aloud from Bulwer Lytton's novel, and asking for directions to the homes of his fictional characters.

Then, in 1869, real-life disaster struck when Pauline died, leaving Lourens with two young daughters. He developed a mystery ailment which required treatment in London which seems to have been cured at Ford Madox Brown's house, when he fell in love with 17-year-old Laura Epps. Her father agreed to her marrying a man twice her age (one of her sisters was already married to the novelist Edmund Gosse). The marriage was long and happy. Laura painted too, specialising in sentimental domestic scenes and Lourens' mystery ailment was soon forgotten. He Anglicised his forename to Lawrence and hyphenated his surname to 'Alma-Tadema' in order to be first in the catalogues so perhaps his 'illness' was simply guilty ambition.

Alma-Tadema throve in the imperial metropolis. Henry James, visiting the Royal Academy's summer season of 1877, objected to Alma-Tadema's 'disagreeable want of purity of drawing', and deficient 'sweetness of outline'. But he could not fault the setting: 'the rendering of yellow stuffs and the yellow brass is masterly, and in the artist's manipulation there is a sort of ability which seems the last word in consummate modern painting'.

The last word seems to have been 'taste'. Alma-Tadema pandered to a high Victorian taste at once affluent and puritanical. It was important to be earnest, even when selling smut.

In The Kiss, 1891, a beautiful young mother bends to kiss her daughter; the 'sweetness and light' that Matthew Arnold attributed to the Greeks. But The Kiss is really two pictures. In the foreground, the mother and child stand on a marble platform. In the background, naked women frolic in the sea. The girl looks at the viewer, but the lines of the marble platform draw the eye towards the bathers. In the bottom left corner, a naked woman stands in the shallows. She also looks the viewer in the eye.

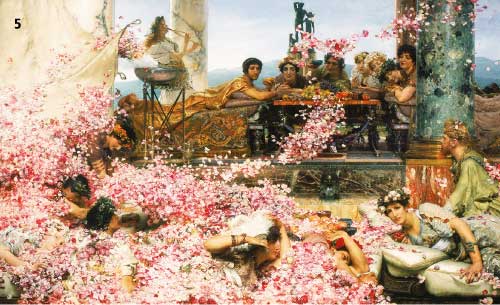

The newly hyphenated painter produced historically hyphenated art. Roman decadence, Greek hygiene, Victorian manners are all rendered with an immaculate, depraved professionalism. The pink tone of the flowers that decorate the barge in Cleopatra, 1883, recur in the flowers with which the emperor drowns his courtiers in The Roses of Heliogabalus, 1888 (5), and recur in the garlands of the scrubbed maidens engaged in A Summer Offering, 1911.

Alma-Tadema was far too much at home in what Whistler derided as 'five o'clock tea antiquity'. The narrative fate of Alma-Tadema's ancients may be unclear, but their motivations and predicaments are as Victorian as an antimacassar. The couple on the kerb in front of the Odeon at Pompeii in Entrance of the Theatre, 1866, could be attending a fancy-dress night at Covent Garden. The two girls in Unconscious Rivals, 1893 (1), could be ingénues at a London ball; even the painting's name derives from modern psychology.

Split between modern motives and ancient settings, Alma-Tadema was the master of the naïve love triangle and its charge of chaste eroticism. In A Foregone Conclusion, 1885, two comely Greek maidens shelter behind a marble banister, as though playing hide and seek in a Holland Park villa, while a youthful suitor rehearses his proposal as he climbs the stairs, ring in hand – but which sister will he marry?

In A Coign of Vantage, 1895 (4), two girls lean over a marble balcony as, far below, a white-sailed ship returns from a long voyage bearing its heroic crew. One girl leans over in excitement; the other half swoons with sexual anticipation. Are they waiting for the same man? In Eloquent Silence, 1890, a virginal couple sits awkwardly on a marble bench. We are voyeurs, enjoying the wavelike texture of the marble, the blue of the marbled sea, and the beautiful young people under the eternal Attic sky. Is the viewer the chaperone aunt – or the goatish old uncle?

Alma-Tadema liked it both ways, and so did his public. He was a storyteller, not a historian; a technically brilliant fan-dancer who knew his price, and numbered each canvas to preempt forgeries. Yet he also understood the value of his art in more than pecuniary terms. Like Bulwer Lytton's novel, his paintings reflect how a modern imperial nation preferred to understand the ancient imperial peoples of Athens and Rome. He raised the past as a mirror to the educated middle class in a sensual, moralising, and historically conscious age.

Modernists, not admitting any trace of their less fashionable inspirations, expunged Alma-Tadema along with other Victorian artists. So the essays in the accompanying catalogue to Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity are a fascinating and necessary correction. Markus Fellinger traces the artist's influence on the young Klimt. Peter Trippi recounts Alma-Tadema's sideline advising Sir Henry Irving on his production of Cymbeline in 1896, designing sets and costumes for his Coriolanus in 1901 and also for Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree's Hypatia in 1893, and Julius Caesar, 1898.

Art Gallery, City of London.

Most striking of all, though, Ivo Blum describes how Alma-Tadema's image of antiquity has become our image of antiquity – through cinema. Cecil B DeMille referred to The Finding of Moses in The Ten Commandments. Ridley Scott used the Pièta-like pose that can be seen in The Death of the First Born, 1872, in Exodus: Gods and Kings. Alma-Tadema remains our contemporary, whether we see it or not, whether we like it or not.

Ruskin, Henry James said, had 'the beauty of his defects'. So did Alma-Tadema. It is ironic that while we might chide Alma-Tadema as a moralist, John Ruskin, the aesthetic conscience of the Victorian age, chided him for the beautiful defect of immoralism. He denounced the fact that many of Alma-Tadema's interiors were seen in twilight with the people in them lolling about or crouching 'in fear or laziness'. The purpose of Classicising art, Ruskin explained in 1875, was 'didacticism': not 'the license of pleasure', but 'the law of goodness'. In The Art of England, his 1883 Slade lectures at Oxford, Ruskin hit Alma-Tadema where it hurt most, in the marbles.

Alma-Tadema's stones had no depth, Ruskin said, only a 'superficial lustre and veining'. His settings were immoral, too: instead of the clarity of the 'southern sun', he gave us the dubious 'cool twilight of luxurious chambers'. There was one painting Ruskin really detested, describing it as 'the most gloomy, the most crouching, the most dastardly of all these representations of classic life... the little piece called Pyrrhic Dance (7) of which the general effect was exctly like a microscopic view of a detachment of black beetles in search of a dead rat'.

© Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence.

He disliked Alma-Tadema for all the decadence that Ridley Scott loved and that he digitised in Gladiator with its lavish fabrics, shadowy interiors and lots of warm flesh on marble. Yet there is more to Alma-Tadema than surfaces. There is architecture, the fabric of history and subtle ambivalences: dilemmas of emotion, interior shadows and decadent foreshadowings. There is the Kiplingesque warning that every empire must fall.

With Alma-Tadema, the art is in the narrative, not the brushwork. Henry James thought that his technical skill made the paintings of his English contemporaries seem like 'schoolboy work' – and James, like Allen Funt with his Candid Camera, was a narrator of staged dilemmas who knew how to get under the skin of his subjects – so perhaps he understood Alma-Tadema in a way that was quite alien to Ruskin and his

other detractors.