Surveying the Silk Roads - across deserts, mountains, steppes and seas

A sumptuously illustrated new book, edited by Susan Whitfield, looks at every aspect of the Silk Roads and its melting-pot of peoples, culture and landscapes.

Silk Roads is simply a convenient term for extremely inconvenient geographies, histories, peoples and spiritual expanses that edge uncomfortably and miraculously towards the unknown, the impossible and the impassable. The fastnesses and vastnesses of these landscapes have nurtured cultures of inner light and secret freedoms, metaphysical daring and notable human courage.

One cannot conceive of these regions in terms of flags and nation-states; Silk Roads studies take us deep into the heart of composite cultures, interdisciplinary ways of understanding and populations in motion that bring us face to face with the complexities of the contemporary globalism unfolding with shocking speed in our own lifetimes...

'There are many ancient places where one finds stones in graves, woods carved with some artistic design.

Sometimes there are letters engraved in the rock of a mountain, on a stone; letters today which no one can read. Yet one endowed with the gift of intuition can read them from the vibrations, from the atmosphere, from the feeling that comes from them. Outwardly, they are engravings, inwardly they are a continual record, a talking record... No traveller with intuitive faculties open will deny the fact that in the land of ancient traditions he will have seen numberless places which, so to speak, sing aloud the legend of their past.'

These evocative words spoken in London in the 1920s by Hazrat Inayat Khan, one of the first Sufi teachers in Europe, evoke the poignance and mystery of central Asian cultures...

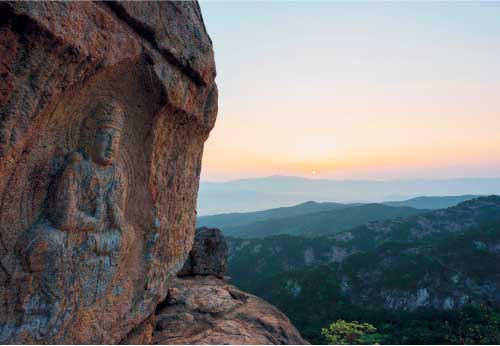

The objects and the peoples featured here are speaking in new ways thanks to new generations of scholars, but their songs are something you can only hear in the inner recesses of your own imagination, meditating on the transience of all things and their rebirth in new forms...

The tombs and stupas are for saints who never died and whose influence will only resonate more deeply after they have left the earth – their holy domes, nestled in the desert... radiating strength, compassion and infinite beauty.

Peter Sellars

'What can I do, Muslims?

I do not know myself.

I am neither Christian nor Jew, neither Magian nor Muslim,

I am not from east or west,

nor from land or sea,

not from the shafts of nature nor from the spheres of the firmament,

not of the earth, not of water, not of air, not of fire.

I am not from the highest heaven, not from this world,

not from existence, not

from being,

I am not from India, not from China,

not from Bulgar, not from Saqsin,

not from the realm of the two Iraqs, not from the land of Khurasan.'

Only Breath by Rumi (1207–1273), translated from the Persian by Bernard Lewis.

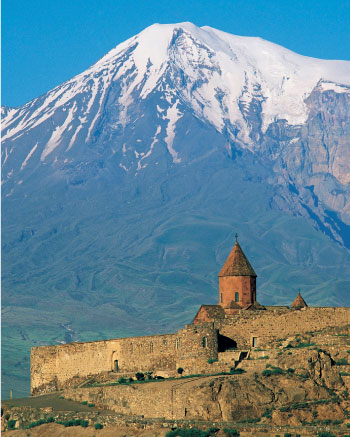

© Robert Harding/Alamy Stock Photo.

There was no 'Silk Road'. It is a modern label in widespread use only since the late 20th century and used since then to refer to trade and interaction across Afro-Eurasia from roughly 200 BC to AD 1400. In reality, there were many trading networks over this period. Some of these dealt in silk, yarn and woven fabrics. Others did not. Some started in China or Rome, but some in central Asia, northern Europe, India or Africa – and many other places. Journeys were by sea, by rivers and by land – and some by all three. Despite these ambiguities, the term has acquired a familiarity and brought regions and peoples, often less well covered by modern historical writings, to greater prominence and accessibility. It could also be argued that the growing popularity of the term has encouraged a more global historical viewpoint.

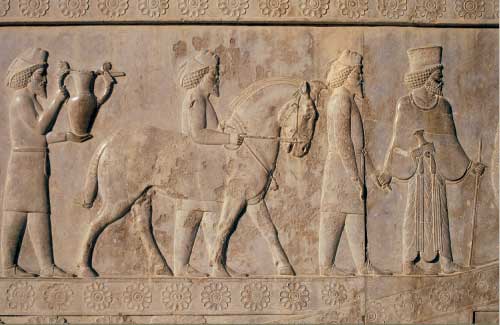

For this reason I have referred to the 'Silk Road', or perhaps slightly less misleadingly, the 'Silk Roads', unashamedly in my writings and exhibitions. If I were to provide a general definition of what I mean by the term, it would be something like: a system of substantial and persistent overlapping and evolving interregional trade networks across Afro-Eurasia by land and sea from the end of the 1st millennium BC through to the middle of the 2nd millennium AD, trading in silk and many other raw materials and manufactured items – including, but not limited to, slaves, horses, semi-precious stones, metals, pots, musk, medicines, glass, furs and fruits – resulting in movements and exchanges of peoples, ideas, technologies, faiths, languages, scripts, iconographies, stories, music, dance and so on.

Central to the Silk Roads is the interaction across 'boundaries', be they chronological, geographical, cultural, political or imaginary… Inevitably major empires, the dates and rulers of which are well known, take centre stage in Silk Road histories, often crowding out the many peoples and cultures who are less well served by history.

This is the case, for example, with many of the steppe cultures, often neglected or presented as passive recipients of the products of neighbouring empires, such as China, Rome or Sasania. But…this was always a two-way interdependent relationship and the steppe is an essential part of the Silk Road story. Similarly, the many small oasis kingdoms of the Taklamakan or Arabian deserts are barely mentioned in most Silk Road histories, despite some having their own languages and art, and thriving for hundreds of years.

As well as providing raw materials, the landscape sustained agriculture and pastoralism, so enabling human life and leisure. It both supported and impeded long-distance travel and, above all, it continues to hold traces that can reveal something of the transmissions across the Silk Roads. The types of landscape through which the Silk Road networks passed include steppe, mountains and highlands, rivers and plains, deserts and oases, and seas.

The landscape is an essential character in any Silk Road story, and too often is given only a minor role. It can, however, also bias or limit our viewpoint. It preserves and destroys without discrimination. For example, the desert sites of eastern central Asia and north Africa have yielded numerous silks, local and imported.

But the monsoons have long destroyed south Asia's textile legacy and we can only reconstruct it from clues in historical texts, from paintings and other artefacts and, very importantly, from textiles exported to distant lands, such as the desert settlements of Cadota and Antinoopolis.

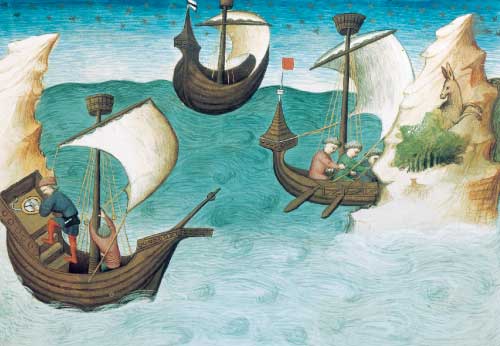

In recent times, the legacy of the sea has started to be uncovered with the growth of maritime archaeology. The hulls of long-sunk ships have preserved their cargoes of ceramics and glass, but direct evidence of the human cargoes of slaves – very much part of Silk Road trade – has long disappeared. Wherever it is possible, or known, such absence is noted.

The landscape's role in the logistics and risks of long-distance trade is also discussed – navigation across seas of sand and water by the stars, fording rivers in spate, negotiating high mountain passes – along with the specialist modes of transport: ships for the sea, yaks for the passes, mules for the perilous mountains and camels for the desert.

The cost and efficiency of the various forms of transport were also a factor: a ship could carry both heavy and fragile goods across great distances far more cheaply than a camel, but the risks were much greater.

The economics of the Silk Roads remains a large gap in our knowledge, mainly because of the lack of evidence to reconstruct it, even for trade in specific goods across discrete sections of time and space. Many cultures did not produce or use coins or use other forms of money.

Texts help in some places at some times, but probably many if not most transactions were not recorded and, even if they were, these were probably among the millions of ephemeral documents long since discarded.

But we can estimate extent of trade through the material legacy, easier with products such as lapis lazuli, which not only has a known provenance but also survives well in the archaeological record. Its rarity also means that it has often retained its original purpose – unlike many metal objects, for example, which have been melted down over the past two millennia. The development of more sophisticated testing, such as isotopic analysis, is providing much useful data and will, inevitably, add to the story.

Susan Whitfield

People travelled across Eurasia by land and sea from the earliest times, but their knowledge, even if passed down orally, was rarely recorded. Nor were there guides to the premodern 'Silk Road', at least until it was conceived in 1877. But there are early geographical descriptions of the known and mythical worlds, and maps made of them.

In ancient Greece, the world according to the 5th-century BC historian Herodotus, for example, included India but not lands to the north beyond the Caspian Sea. For the Chinese, Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas) from the 4th-century BC, gave geographical information, possibly extending to the Kunlun Mountains of central Asia. The expeditions eastwards of Alexander the Great (r 336–323 BC), and of Zhang Qian (164–113 BC) westwards extended the knowledge base considerably.

The territories conquered by Alexander were settled by Greeks and their subjects and became kingdoms within the Graeco-Roman world. China similarly expanded and included information, geographical and otherwise, about these 'western regions' in its official histories: for empires controlling foreign lands, such data were vital.

In the 2nd century AD, Ptolemy of Alexandria (circa 100–168) mapped the world known to the Roman empire with greater precision than ever before, showing Asia as far east as China but not the ocean beyond. His Geography contained a gazetteer giving some 8000 place names with co-ordinates of latitude and longitude. He included instructions on how to construct a map allowing for the curvature of the earth, identifying features such as the Himalaya, the Ganges, the southeast Asian peninsula and Serica Regio, the name by which China was known in the Graeco-Roman world, meaning the 'Kingdom of Silk'. Ptolemy claimed that he consulted all available geographical descriptions and travellers' accounts but does not give a list. He names the peoples inhabiting each region, but scarcely mentions their activities or material cultures.

Many centuries later, as Islamic rule spread to central Asia, their cultures developed their own schools of sophisticated map-making, in advance of those of their Byzantine neighbours. Al-Kashgari (AD 1008–1105) is one of the few cartographers known from central Asia, his map prepared as part of his great Turkic dictionary. Cartography skills reached their culmination with al-Idrisi (AD 1100–1165), who was active in Norman Sicily. He was a disciple of Ptolemy, and constructed a series of regional maps that dovetailed together within a rational framework to form one unified map of the known world. The al-Idrisi maps and accompanying book offer a wealth of topographical and settlement detail, the maps focusing on three features: place names, mountains and water. The book also gives itineraries with distances and includes a rich array of place names in central Asia, especially around Sogdiana, suggesting a strong interest in this area – and good sources of information.

Chinese pilgrim-monks, famously Xuanzang (circa AD 602–664), also produced itineraries with distances. The accuracy of these is seen in their largely successful use in modern times to identify significant sites of the historical Buddha by Alexander Cunningham (1814–1893) and places in the Taklamakan desert by Aurel Stein (1862–1943).

Chinese learning, like Chinese society as a whole, was very much under centralised, imperial control, and the maps produced were predominantly made to show political, administrative divisions. Although very accurately plotted, they were at a small scale. The rise of the Mongols and their spread across Eurasia changed this, with the Mongol emperor, Kublai Khan (r 1260–1294), commissioning a world map in 1286. This must have brought greater knowledge to many more people, not just the merchants and diplomats who visited distant lands, and it formed the basis for a map of the succeeding Ming empire (1368–1644) in China.

In medieval Europe, Marco Polo's (1254–1324) account of his overland trading journey to China became one of the most popular books of the time, and its descriptions of the wonders of China, called Cathay, was hugely influential in preparing the way for the subsequent so-called European Age of Discovery. Yet one of the surprising things about his book is that it was not accompanied by a map, and scholars have argued continuously about the route followed. It was left to others to plot his narrative in map form, and the Catalan Atlas is the earliest and the best known. Produced around 1375 in Majorca, its mapping of Asia represents a real advance in European knowledge.

Its most famous feature is the vivid picture of a group of merchants crossing the desert on horseback with their goods carried by Bactrian camels (only dromedaries were ridden) as shown in another image of the trans-Saharan routes.

The caption reads: 'This caravan has set out from the Kingdom of Sarra [the Caspian region] to travel to China'.

Peter Whitfield

These brief extracts from Silk Roads: Peoples, Cultures, Landscape give a glimpse into the exotic excursion undertaken by its authors and a glimpse of the fascinating facts and gorgeous illustrations that pervade every page. From steppe to desert, over rivers and mountains and across empty plains, from lapis lazuli mines in Afghanistan to ruined cities buried in the sands, when you open this book you can almost smell the fragrant wafts of frankincense and myrrh from Arabia and hear the swish of a silk sash from China. Its great empires rose and fell but its vast landscape remains and its wonderful artefacts show what these beacons of civilisation produced along trade routes stretching from Peking to Venice. • Its editor Susan Whitfield, an expert on the Silk Roads, is a scholar, traveller, lecturer and curator, who spent 25 years at the British Library as curator of the Central Asia manuscript collection. She invited more than 80 of the world's leading scholars to share their expertise and shed light on aspects of that most alluring of subjects – the Silk Roads.