Monumental Mexico - the art and culture of the Olmecs

The Olmecs are best known as the creators of Mexico’s first civilisation, and for making some of the country’s most extraordinary works of art. Claudia Zehrt surveys a major new exhibition that aims to bring their history and culture to a European audience, and includes many fascinating pieces that have never left Mexico before.

Many visitors to Mexico travel to see the famous archaeological sites in the country’s central and southern regions. They explore the temple-pyramids of the Maya, the grandeur of the ancient city of Teotihuacan, or the remains of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan (underneath Mexico City). Far fewer tourists make it to the archaeological sites and museums along Mexico’s Gulf Coast – a region mainly encompassed by the modern-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco. Here, those who do undertake the journey find themselves in a subtropical wetland, criss-crossed by many rivers and creeks, mostly made up of floodplains along the coast and bounded by the mountains of the eastern Sierra Madre to the west. It is in this fertile area that we see the earliest beginnings of complex civilisation in Mesoamerica – the historical region that extends from central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. And it is here on the Gulf Coast that we find the first examples of many of the traits and motifs that would in subsequent millennia become defining characteristics of Mesoamerican art and iconography.

©Secretaría de Cultura. INAH. MEX-CANON. Archivo Digital de las Colecciones del Museo Nacional de Antropología / Colección Centro INAH Veracruz

For those unable to make the journey to Mexico’s Gulf Coast, this year brings good news. A major new exhibition, featuring some of the most beautiful examples of art and archaeology from the area, is scheduled to open at the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris in October 2020. Featuring many pieces that have never before left Mexico, the show – entitled The Olmecs and the cultures of the Gulf of Mexico – aims to bring the history of the region closer to a European audience, providing a fascinating introduction to its art and an insight into the shared cosmovisión (‘world view’) of its people.

From about 2000 BC – the beginning of the time known in the region’s history as the Formative period – Mesoamerica saw increased sedentism, as more people began to live in one place permanently. Supported by maize agriculture, this period also saw the development of larger centres and ceremonial structures. On the southern part of Mexico’s Gulf Coast, the settlements grew large and socially complex by about 1600 BC – and archaeologists and art historians in the 19th century started calling the distinct style of art emanating at that time from the area the ‘Olmec’ style. The word ‘Olmec’ comes from the Aztec-language (or Nahuatl) name for the people living in the Gulf Coast region. (‘Olmecatl’ means ‘rubber people’ – so-named probably because one of the area’s natural resources is the sap of the rubber tree. As with many archaeological cultures, the name the Olmecs used for themselves is unknown.)

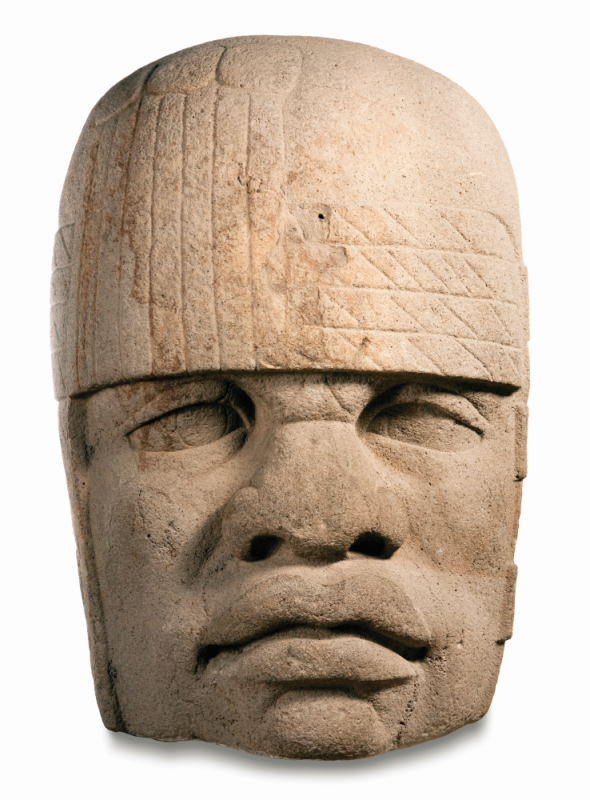

Visitors this autumn to the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac will be greeted by one of the most recognisable objects left behind by the Olmecs: an example of the famous sculptures known as ‘colossal heads’. At ‘just’ 6 tons in weight, and standing no more than 178cm tall, it may be among the smallest of the 17 known colossal heads of the Olmec world – but it will nevertheless serve as a striking introduction to one of the oldest complex cultures of Mesoamerica.

The head was found at San Lorenzo, the first large Olmec site – in the south-east of modern-day Veracruz – which during its flowering from about 1400 BC to 1000 BC covered an area of 70,000 hectares. At the time, it was the largest community in Mesoamerica, with an estimated population of up to 10,000 people. The site itself is built on a large plateau surrounded by a floodplain. It consists of largescale architecture, temples, and plazas, as well as residences of all sizes. The most important, largest, and well-built residences, as well as ceremonial and administrative structures, sit on top of the plateau, with the smaller and poorer homesteads and houses constructed further down towards the plain.

©Secretaría de Cultura. INAH. MEX. Catálogo Digital Museo de Antropología de Xalapa. Universidad Veracruzana

In this early large centre of the Olmec heartland, archaeologists found ten colossal heads, partially set up in rows, like a procession, in the central area of the site. The heads are of various sizes, weighing up to 28 tons, and each has unique features and individualised headgear – so they seem to depict different people. One hypothesis is that the heads portray the rulers of San Lorenzo and that the example to be shown in Paris, known as ‘Colossal Head 4’, shows the ruler as an older man with a wrinkled brow. As well as being master carvers, who recycled and recarved these large stone monuments over time, the inhabitants of San Lorenzo were also experts in working greenstone, creating pyrite mirrors, and expressing their beliefs in the form of terracotta figurines and earthenware pottery. Among the motifs that were to become typical of the Olmec art style are a pronounced cleft in the middle of the head, a downturned mouth, and almond-shaped eyes – as can be seen in the serpentine figurine from La Merced in Veracruz, one of the satellite settlements of San Lorenzo.

For about 500 or 600 years, the rulers of San Lorenzo used political ideologies, their polytheistic belief system, and control over large trade networks to expand their influence over this part of the Gulf Coast. Secondary centres were created to ensure control over resources (like the basalt used to make the colossal heads, which came from the Tuxtla Mountains to the north of San Lorenzo) or trade routes. Political integration and social cohesion were in part created through rituals, ceremonies, and pilgrimages, many of them involving stone monuments, which may have been created and then distributed from the centre. One such group of stone sculptures was found at the small site of El Azuzul, to the south of San Lorenzo, the arrangement of which can be admired in the new exhibition. The two seated human figures in the group, which also includes a pair of feline figures, might even point to the early beginning of the important and long-lasting Mesoamerican myths surrounding the ‘Hero Twins’ and their travails in the underworld. (Much later, in colonial times, these were written down in highland Guatemala as the Popol Vuh.)

©Secretaría de Cultura. INAH. MEX-CANON. Archivo Digital de las Colecciones del Museo Nacional de Antropología

A striking example of the importance to Olmec culture of pilgrimages and offerings made around water is to be found in the wooden busts discovered at the spring of El Manati, another small site close to San Lorenzo. There, the waterlogged environment facilitated the survival of usually perishable materials – so not only were offerings made from greenstone uncovered, but also rubber balls, showing the early importance of the Mesoamerican ‘ballgame’, a sport with ritual associations, played in the region since at least 1650 BC. But the most remarkable finds from the site are a group of wooden busts, whose features show similarities with the typical faces of so-called ‘Olmec babies’ – mainly ceramic figurines of what appear to be pudgy babies or infants.

Another typical Olmec motif can be seen in the anthropomorphic figures of humans with feline features known as ‘were-jaguars’. (The prefix ‘were-’ comes from the Old English wer, meaning ‘man’.) The were-jaguar theme may be connected to shamanistic beliefs about animal transformation and a shaman’s spirit companion. Alternatively, there may be an iconographic connection between caves, rain, and jaguars, which turned into the main rain-god motif in many parts of Mesoamerica. Monument 52 from San Lorenzo is a good example of a were-jaguar, with its flared upper-lip, downturned mouth, and almond-shaped eyes. The figure’s cleft headdress designates it as the Olmec rain deity, while the groove on its back may be associated with the water drainage system at the site.

Though the lack of any written record means there is much that must forever remain mysterious about the Olmecs, the wide dispersion of objects and artefacts in the Olmec art style allows us to appreciate the number and distance of early connections in Mexico and Central America. Although the most typical stone monuments seem to have been limited to the Olmec heartland at this time, Olmec-style ceramics are found throughout early Mesoamerica: they were locally made in the Valley of Mexico, near modern-day Mexico City, for example; and imitations of style and surface treatment can be found as far afield as Guatemala and Honduras. Today, archaeologists can reconstruct the networks of trade and exchange through these ceramic artefacts, but that trade must also have incorporated many materials that have not survived through time – including animal skins and furs, plants and fruit, and wooden, shell, and bone objects. Some artefacts – such as stingray spines, turtle shells, mosaics of pyrite and other stones, conch-shell trumpets, greenstone, and obsidian – give at least an idea of the items that were widely traded by the elite. These scarce and highly valued materials were prestige goods that underlined contacts, loyalty, and alliances between the rulers and elites of the different regions that were establishing themselves during the period, helping to centralise authority and emphasise growing social stratification and power structures.

©Secretaría de Cultura. INAH. MEX-CANON. Archivo Digital de las Colecciones del Museo Nacional de Antropología

Around 1000 BC, we can see that San Lorenzo encountered difficulties and ceased to be the centre of power in the Olmec world. The exact causes of its decline are unclear, but the growing influence of, and rivalry with, the newer centre of La Venta, in the modern Mexican state of Tabasco, might have something to do with it. People moved away from San Lorenzo, structures were abandoned, and some monuments were destroyed.

Meanwhile, from about 1000 BC to 400 BC, La Venta developed into the main Olmec centre, the successor to San Lorenzo. The canon of monumental art was continued there – another four colossal heads have been discovered at the site, along with large carved thrones or altars resembling those already seen at San Lorenzo. The La Venta site also has a large earthen pyramid – still 34m high today, after nearly 3,000 years of erosion – and a sacred precinct, known as ‘Complex A’, where archaeologists found a plethora of offerings and five formal tombs. The workmanship evident in the carvings in jade, basalt, and semi-precious stones discovered not only at La Venta, but also in the wider Olmec region, shows the high levels of sophistication reached by Olmec artists. Their accomplishment can be seen in the exhibited statue ‘El Señor de las Limas’, found 130km from La Venta in the upper regions of the Coatzacoalcos River. This exquisitely carved and polished greenstone statue, which stands 55cm tall, shows a cross-legged man holding a infant were-jaguar in his arms: the main figure has incisions on his shoulders and knees that show mythological beings – allowing us to piece together more information about the beliefs of the Olmecs.

From La Venta itself, the group known as ‘Offering 4’ can be seen as it was placed into the ground in the mortuary of Complex A: a cache made up of 16 figures made from semi-precious stone and six thin celts (adze- or chisel-shaped stones) with engravings, which might signify columns or stelae (or maize sprouts). The idea is that the offering shows a procession of some kind, but it is unclear if the figures depict rulers and nobles, or mythical personages. This cache was placed in a small pit on top of one of the so-called ‘Massive Offerings’ at La Venta: they consist of carefully finished and very large serpentine blocks, covered in massive amounts of clay fill.

Although La Venta also went into decline and was abandoned around 400 BC, the legacy and influence of the Olmecs on the rest of Mesoamerica was substantial. The rulers of La Venta had forged an even larger and denser network of trade and contacts than their San Lorenzo counterparts, and the influence of the Olmec style on objects, monuments, and architecture outside the Olmec heartland can be seen widely. The site of Chalcatzingo, hundreds of kilometres away in the country’s Central Highlands, for example, was a strategic regional centre of contact between the Valley of Mexico and the Gulf Coast, and although not Olmec itself, is renowned for its Olmec-style monumental art and iconography. On the other side of the isthmus, the influence of the Olmec tradition is visible in iconography and architecture at sites along the Pacific coast of the Mexican state of Chiapas, as well as in Guatemala and El Salvador.

Throughout Mesoamerica, the power of the elites was growing, as societies became more and more stratified during the Late Formative period (300 BC-AD 200), and signs of rulership and power are carved into jade and greenstone, scarce and precious materials, with many of them in the style we know from the Olmec heartland. Large basalt statues like ‘The Prince’ from Cruz del Milagro, Veracruz, vividly show the power of the ruler in a physical form.

©Secretaría de Cultura. INAH. MEX-CANON. Archivo Digital de las Colecciones del Museo Nacional de Antropología

By the first centuries AD, the largest cities and structures in Mesoamerica were being constructed in the Maya area (which encompasses south-eastern Mexico, all of Guatemala and Belize, and the western portions of Honduras and El Salvador) – at the settlement of El Mirador in northern Guatemala, for example, or in Mexico’s Central Highlands, where we see the beginnings of the large metropolis of Teotihuacan. But the widespread influence of the Olmec style can be seen at many sites in Mesoamerica during what is known as the Classic period (AD 200-900) – and although ideas and concepts (like the ‘Olmec dragon’ or Earth Monster, the watery underworld and rain deities, and veneration of rulers and their ancestors) change and develop according to local styles, the Olmec legacy nevertheless remains visible.

One thing the Gulf Coast exhibition makes very clear, however, is that the decline of the Formative period Olmec centres in Veracruz and Tabasco does not mean the decline of the complex and dynamic cultural history of the area. Due to its strategic location at the bottleneck of trade routes and in an area full of natural resources, other cities established themselves during the Classic and Postclassic (AD 900-1521) periods, creating a diverse and changing mosaic of habitation stretching over three millennia.

As the objects included in the Paris exhibition will show, the wider Gulf Coast region (including the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz, Tabasco, Tamaulipas, Querétaro, and San Luis Potosí) was home to a range of vibrant communities, which continued to take advantage of their favourable location along trade routes by cultivating connections to the cities of Teotihuacan and later Tenochtitlan in Central Mexico, and to the Maya area in the south.

One of the lesser-known but fascinatingly rich cultures of the Gulf Coast area was that of the indigenous group known as the Huastecs. Though it remains underexplored archaeologically, the Huastec area – centred in the region around the Tuxpan and Pánuco Rivers – has yielded an incredible legacy of beautiful stone sculptures, including the Classic era kneeling woman from Tuxpan in Northern Veracruz that will form part of the Paris exhibition. The depiction of women is one of the characteristics of Huastec sculpture, a body of work that contains at least as many females as males – a fact that perhaps finds a later echo in reports about the power and importance of Huastec women in the period immediately before the Spanish conquest.

Huastec sculpture is, at least in part, distinguished by its comparative naturalism, as can be seen from the piece that will bid visitors to the exhibition farewell: the spectacular female torso from the site of Tamtoc in San Luis Potosí, sometimes called the ‘Venus of Tamtoc’. Found in 2005, this life-like and nearly life-sized figure was part of an ancient offering at a spring at the site, and probably dates to the first centuries AD. The decoration of raised dots on the nude body probably represents scarification – the deliberate process of creating wounds in order to cause indelible markings on the flesh – and is possibly connected to the social status of the woman depicted, or perhaps is a symbol related to ritual or mythology. Again, in the absence of religious texts or related explanations, the interpretation and understanding of such complex and detailed decorations is difficult. The intricate carvings on the body of the ‘Huastec Adolescent’ from the site of Tomohi, to take another example, might depict tattoos or body paint, and have been interpreted as a representation of the god Quetzalcoatl, or as being connected to young maize plants and associated ceremonies. From the position of the young man, who dates from AD 900-1250, it is likely that the statue was used as a standard-bearer, perhaps on one of the large local plazas where rituals would have taken place.

©Secretaría de Cultura. INAH. MEX-CANON. Archivo Digital de las Colecciones del Museo Nacional de Antropología

During the 15th century AD, the Gulf Coast was conquered by the Aztec Empire, which flourished from about AD 1300, and the different communities living in the area had to pay tribute to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in Central Mexico. When the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés landed on the Gulf Coast near Veracruz in 1519, he found willing allies in the local Totonac peoples, who played a significant role in enabling him subsequently to conquer and defeat the Aztecs at Tenochtitlan in 1521. By this time, the Gulf Coast region was a thriving multicultural area, with about 20 different languages and different cities built around trade, craft and the abundant local resources. The Olmecs and the cultures of the Gulf of Mexico will be a rewarding experience for those who wish to understand the artistic and cultural traditions of this fascinating region, and to see the development of the enduring motifs and craftsmanship of Mesoamerican cultures from their earliest beginnings through three millennia of history.

The Olmecs and the cultures of the Gulf of Mexico at the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac is due to open in the autumn of 2020 as we go to press.

This exhibition is organised in collaboration with the Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia and the Secretaria de Cultura, Mexico.

Our thanks go to Steve Bourget, archaeologist and curator at the Americas Department, musee du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac and Serena Nisti for their help. Our acknowledgement to the original curator, Rebecca Gonzalez Lauck, Archaeologist and researcher at the INAH-Tabasco, Villahermosa, head of the archaeological project of La Venta, associated with the Museo Nacional de Antropología de Mexico.